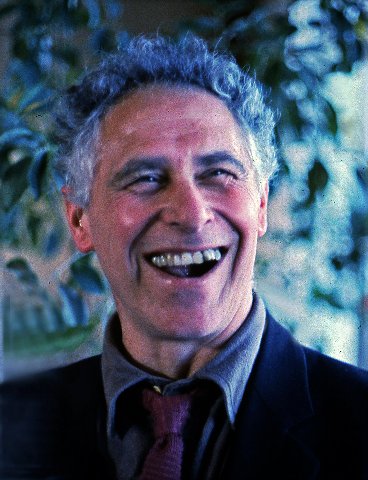

Realist Painter Alfred Leslie at 95

Boston Connections at the MFA and BU

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 28, 2023

The realist painter Alfred Leslie was born Alfred Lippitz on Oct. 29, 1927, in the Bronx. His parents, Irving and Jeanette (Wolff) Lippitz, were German immigrants. He has died at 95 from Covid complications.

He was gaining recognition as an emerging Second Generation Abstract Expressionist. Little of that early work survived. Most of it was destroyed in 1966 in a fire that claimed the lives of 12 firefighters as it engulfed three buildings in the Flatiron district of Manhattan. It was a major news story at the time which I read about in the Village Voice. That prompted me to visit the site.

“It was like a horror film,” he told The Times. “My whole studio burst into flames. I stood on the street and saw my paintings burning through the windows.” A planned exhibition of his grisaille paintings at the Whitney Museum of American Art had to be canceled.

By then he had transitioned from abstraction to larger than life, grisaille figuration. An iconic, frontal, confronting self portrait was included in the Whitney Annual. It was a shocking visual manifesto as the work was like none other in that survey that is noted for taking the pulse of American art.

The work was defiant and exuded the spirit of the Beat Generation which he was allied with. The deadpan image depicted the artist with an unbuttoned shirt, bulging abdomen, scruffy pants and the demeanor of an artist at work in the studio.

He with Jack Beal, Alex Katz, William Bailey and Philip Pearlstein was part of an evolving movement which has garnered grudging respect from the mainstream critical establishment. At the time figuration was regarded as reactionary anathema by Clement Greenberg the high priest of criticism.

Then and now the leading champion of this niche of contemporary American art was John Arthur. For a time he showed many of these artists as curator of the Boston University Art Gallery. Leslie was on the faculty of the conservative Boston University School of Fine Arts. He commuted from New York as did another defector from abstract expressionism, Philip Guston.

While Guston pursued a radical, cartoonish manner, most notable for controversial depictions of the Ku Klux Klan, Leslie reverted to emulation of the Baroque master Michelangelo Merisi AKA Caravaggio (1571-1610).

There is some irony as Caravaggio, a ruffian and murderer, represented a radical departure from Mannerism the artsy and obfuscating decline and fall that tailed off from the stylist downward spiral of the Renaissance. He brought radical realism to epic, life-sized religious paintings. Shockingly, he depicted the dirty feet of the bloated corpse of Mary.

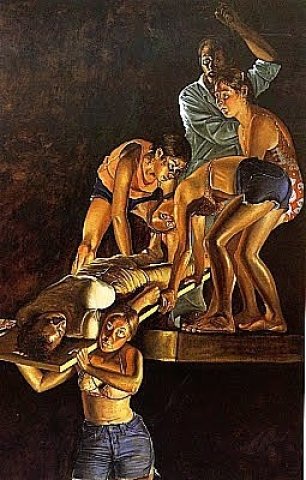

That connection to Caravaggio is conveyed most precisely and masterfully in a depiction from a series of works "The Killing Cycle" related to the death of poet Frank O’Hara. He was struck and killed by a Jeep while on the beach at Fire Island. The poet was a friend and collaborator of the artist. He worked on the paintings and studies for fifteen years.

For a monumental painting Leslie appropriated Caravaggio’s composition “The Entombment” where the body of the dead Christ is being lowered into the grave from which he would rise on Easter morning. In the O’Hara painting the protagonists are dressed in cutoff jeans which elides them from the Baroque to contemporary art.

Caravaggio developed a style of dramatically lit, dark paintings and night visions. The technique inspired the Candlelight painters of Utrecht as well as the French artist Georges de La Tour (1593 -1652). Notably no candles appear in paintings by Caravaggio.

What’s modernist about the realism of Leslie is that it is deeply embedded in Baroque technique but he opted not to pursue its narrative tropes. The O’Hara paintings are in that sense singular.

His deadpan approach to nudes and figuration follows the trajectory of Pearlstein. It differs from the work of Jack Beal (1931-2013). John Arthur connected me to the artist when he was working on a series of four, large, narrative paintings on the History of Labor. It was a commission for the lobby of the new Department of Labor in Washington, D.C.

There were a number of visits and weekends to the studio in Oneonta, New York. Jack spoke passionately about Caravaggio and a commitment to create works with monumental significance and historical relevancy. He made a point to distinguish between photo realism and his approach of "eyeball realism." It is well known that Vermeer relied on camera like devices in his work. In general photo realism is notable for the banality of subject matter and deadpan execution. While Leslie, Beal, Estes, Pearlstein and others were masterful and nuanced painters.

Despite the big chill of the art world’s curators and critics, then and now, realism has enjoyed a solidly bourgeois market. With rare exceptions, however, it has not fared so well in the secondary market.

The New York Times obituary states that “In 1976 the Museum of Fine Arts Boston organized a retrospective of his work that traveled to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.”

It is significant that the Times does not credit John Arthur as curator and completely misses the complex back story. The omission leads the reader to assume that the then stodgy and conservative MFA was hip enough to show Leslie.

That was hardly the case as the contemporary program was curated by Kenworth Moffett, a zealous formalist, and Greenbergian. Much to his credit, however, Ken was generous in supporting minimally funded projects by curators with very different approaches. Arthur’s Leslie and Richard Estes shows were hits for the museum. They drew audiences far in excess of Moffett’s efforts.

While Moffett was supportive of Arthur’s taste he did not follow through with acquisitions for the collection. As he told Arthur at the time “Realism is too expensive.” The contemporary department he founded in 1971 was the Cinderella of the MFA.

Famously Moffett turned down a potential gift from Guston offering the pick of the studio. The MFA later acquired a Guston but the bulk of the estate was recently bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It underscores the many tales of what might have been. Whatever the museum would have paid for a Leslie or Estes is a pittance of what they are worth today.

The greater irony is that Boston is most noted for its figurative tradition which is precisely why Guston and Leslie were teaching at BU.

Leslie also did interesting experimental films. I had seen one “Pull My Daisy” (1959) at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge. It was a collaboration with the photographer Robert Frank. It was adapted by Jack Kerouac from the third act of his unfinished play “Beat Generation” and filmed in Leslie’s loft with music by David Amram. The film has a motley crew of a cast including poets Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky and Gregory Corso and the painters Larry Rivers and Alice Neel.

In sync with the annual Kerouac Festival in Lowell I curated a Beat exhibition for the New England School of Art & Design/ Suffolk University. I collaborated with curator Linda Poris of the Brush Gallery in Lowell.

It was an ambitious project. I contacted Leslie and asked if we might screen “Pull My Daisy” and invite him to come talk about it. He wasn’t interested.

There were other complications for the show. I had met Allen Ginsberg and arranged to borrow works from Tibor de Nagy Gallery. He died shortly before the show and the offer was withdrawn. Similarly Elsa Dorfman reneged on a commitment to show her Polaroids of Ginsberg. 'They're too valuable now" she argued "So I can't let you have them."

Poris managed to borrow those images from the collection of the Danforth Museum. I made do with works by Ginsberg and Dorfman in my own collection as well as borrowing works by Fred McDarrah, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Gerard Malanga among others.

Conjuring memories of Leslie one thinks of the many artists in Boston who felt and absorbed his enormous presence.