Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed

Riveting Selection of 43 Works at Met Breuer

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 29, 2018

Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed

Through Feb. 4 at the Met Breuer, Manhattan

The exhibition of 43 paintings "Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed" continues through Feb. 4 at the Met Breuer in the former Whitney Museum building on Madison Avenue a short walk from the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Fifth Avenue.

On extended lease the annex allows expanded modern and contemporary art programming for the encyclopedic museum.

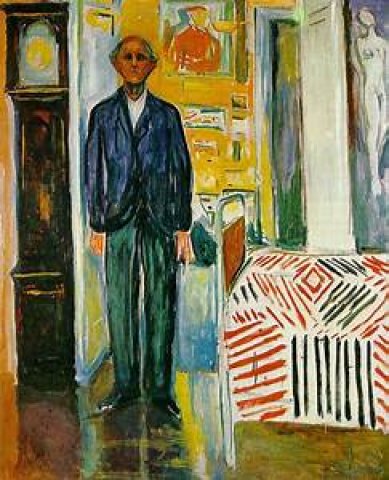

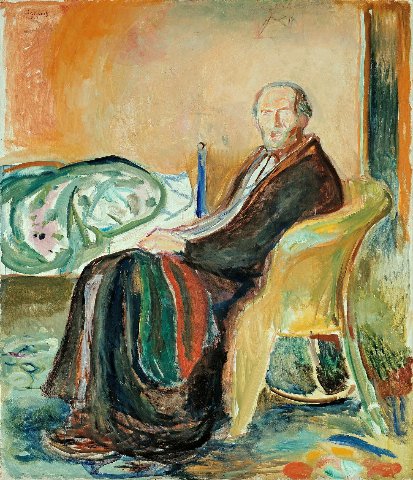

The riveting special exhibition, which is organized thematically, derives its title from a painting which has pride of place on a panel dividing the space as one enters the first gallery. It was painted between 1940 and 1943 a year before the death of the artist.

That occurred in Norway while the world was at war. He had lived for a time as a young man in Germany during the formative time of the expressionist movement. As a badge of infamy he was denounced by the Reich and included in its 1937 exhibition “Entartete Kunst” (“Degenerate Art”).

The regime purged German museums of works of its most renowned artists. Rather than destroy them, however, many key examples were sold at auction in Switzerland. It’s how Harvard’s Busch Reisinger Museum acquired several masterpieces but no prominent works by Munch.

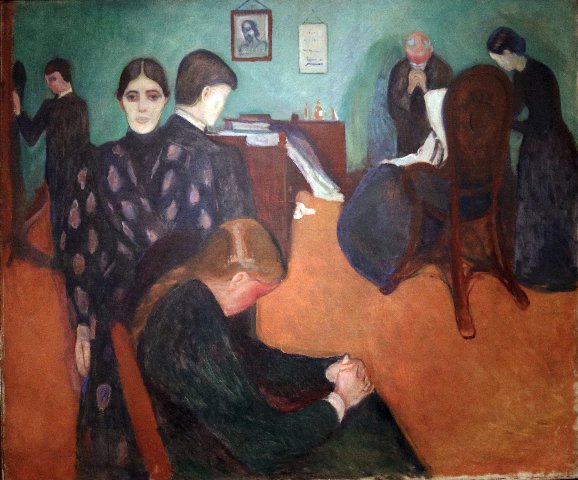

Being on Hitler’s official enemies list of artists arguably exacerbated the depression and alcoholism that the artist struggled with. He was haunted by the death of his mother and sister. Disease and mourning were themes in the work represented in this exhibition. He was also unlucky in love and at the termination of a relationship shot himself in the hand.

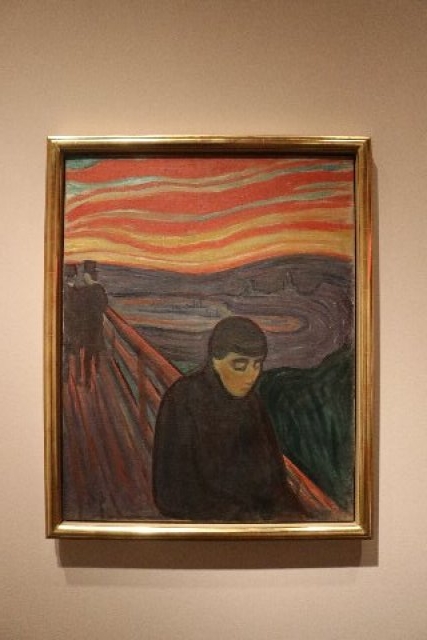

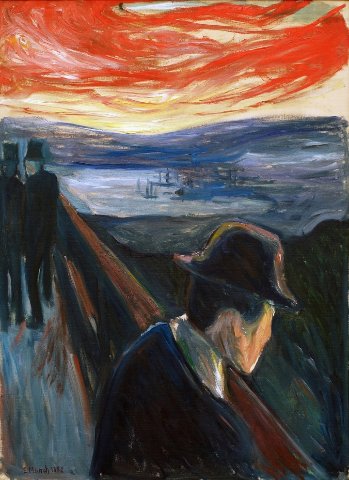

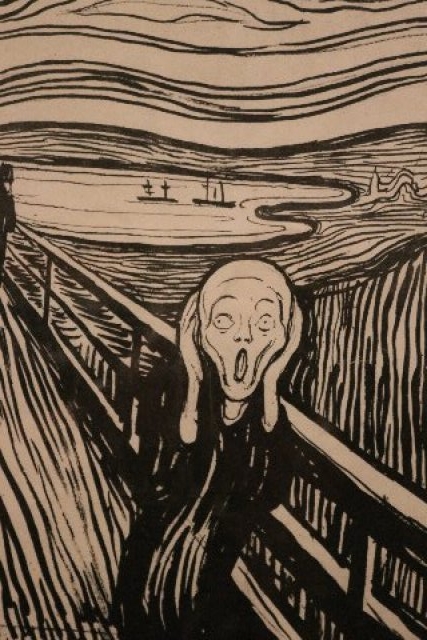

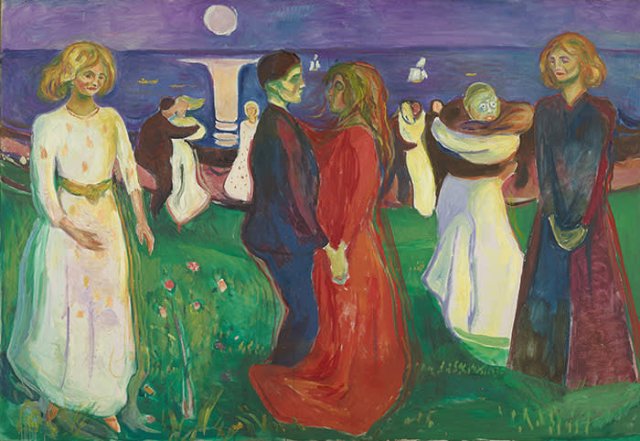

The work of the artist represents paradigms of the ennui and angst of the human condition. The iconic image is The Scream of which he created three paintings and editions of prints. The life and work of the artist (1863-1944) in emblematic of a glass is half empty sensibility identified with the culture of Scandinavia. It is evident in the plays of Ibsen and Strindberg and, skipping generations, the films of Bergman.

There is however, no comedy or irony that balances the work of Munch which ranges from dark to darker.

"My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness," he once wrote. "Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder....My sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art."

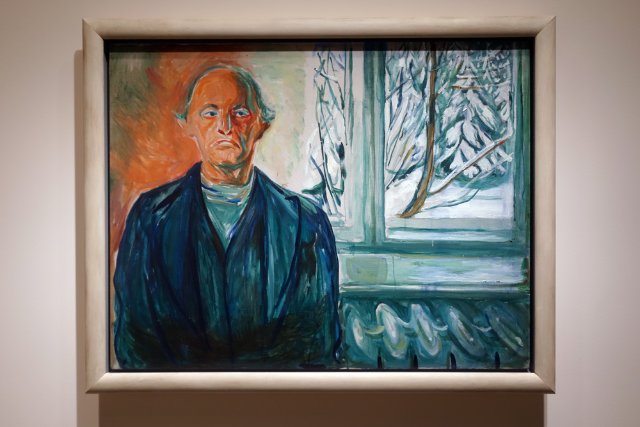

In the dead of winter visiting such an exhibition invites introspection if not depression. It is the season, however, when we are conditioned for the deepest introspection. On many levels this was a rich and riveting experience. There were many close encounters with renowned and rare works. The first room spans decades of his career and stages of introspection with 16 self portraits some of which I knew only through reproductions.

He was a prolific artist, creating approximately 1,750 paintings, 18,000 prints, and 4,500 watercolors, in addition to sculpture, graphic art, theater design, and photography.

More than half of the works on view were part of Munch's personal collection and remained with him throughout his life. They are on loan from the Munch Museum in Oslo.

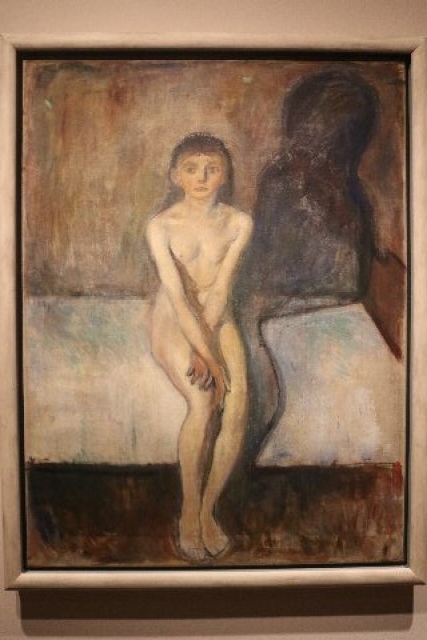

Seven works in the exhibition are shown in the United States for the first time: Lady in Black (1891); Puberty (1894); Jealousy (1907); Death Struggle (1915); Man with Bronchitis (1920); Self-Portrait with Hands in Pockets (1925-26), and Ashes (1925). Also on view will be Sick Mood at Sunset, Despair (1892)—the earliest depiction and compositional genesis of The Scream, one of the most recognizable images in modern art—which is being displayed outside of Europe for only the second time in its history.

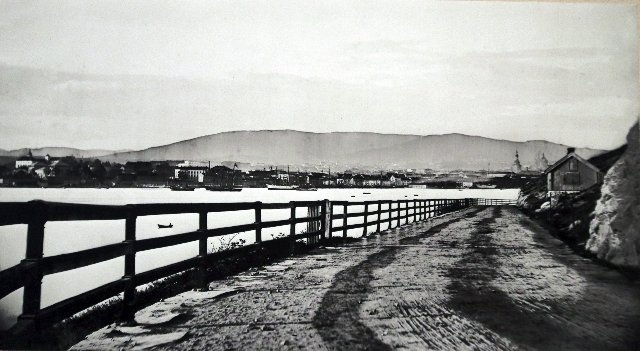

The Munch Museum owns one of the Scream paintings which is not on view but two of the three companion works (usually hung as a triptych) are displayed. A print provides the reference point. In 1999 we visited an enormous Munch exhibition at the Shanghai Museum of Art that included a version of The Scream. The exhibition was organized in honor of a visit by Harald V the King of Norway.

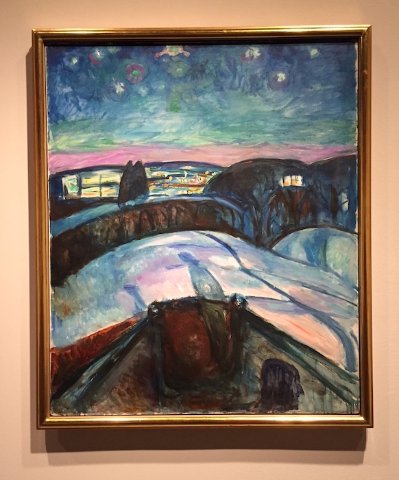

Critics writing about the Met Breuer exhibition have discussed a dichotomy separating the early work as his most significant and then a decline resulting from various bouts of depression and alcoholism. The later work includes bucolic and genre paintings in the manner of the Barbizon painters particularly the depictions of peasants by Millet.

Given the limited number of works on view speculation on the diminished quality of the late period is not possible. A particularly harsh review suggested that we have been spared the bathos. Based even on a limited sample, however, I beg to differ.

Great artists evolve and change dramatically during the span of their careers. There is often a stark difference from the early works that established their careers and then arguments about alleged decline. It is often a challenge fully to engage the struggle and triumph of creators dealing with erosions of health, prowess, mental stability, and self assurance. It takes a keen eye to see greatness in the late work of Titian, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Goya, Munch or Picasso.

That signature late portrait in this exhibition, for example, is strikingly different from other works in that gallery. It is as resonant as the Delphic Oracle or All the World’s a Stage by Shakespeare. Regarding the human condition all phases and stages of life are equally redolent of beauty and poetry.

In this capsule Munch show we observe the artist returning to themes throughout his oeuvre. It is more productive to credit the nuances and variations than to focus on aesthetic absolutism. Such pronouncements and dismissive evaluations are more often about the viewer and critic than inherent in the intentionality of the work itself. The mountain should not be expected to come to us.

Consider for example, the aged and deranged character of Beckett’s “Krapp’s Last Tape.” There is that devastatingly poignant passage when he spools up and listens to himself as a sanguine youth. At the end of his life Harold Pinter performed the role in 2006. No reviews discussed the diminished power of the British playwright. I will always remember the compelling interview he gave to Charlie Rose.

Rose, of course, has been outed and disgraced. It is not prudent to praise his work. Now a museum exhibition of portraits by Chuck Close has been cancelled resulting from accusations of sexual misconduct with models. Reporting on this the Times surveyed museum officials on what to do with known offenders in collections from Caravaggio (murder) Cellini (rape), Klimt and Shiele (abuse of models and children) to the misogyny of Picasso and alleged pedophilia of Balthus. The Vienna Actionist, Otto Muhl, was convicted of sex with minors in his commune. Biographer John Richardson reported that Francis Bacon had an abusive, sadomasochistic relationship with Peter Lacy.

That informs how one looks at the sexual work of Munch. There is long standing debate about paintings and prints such as Madonna and the so called Vampire (not his own title). The Met show has versions of Madonna and Vampire ( a woman seemingly sucking blood from the neck of a submissive male).

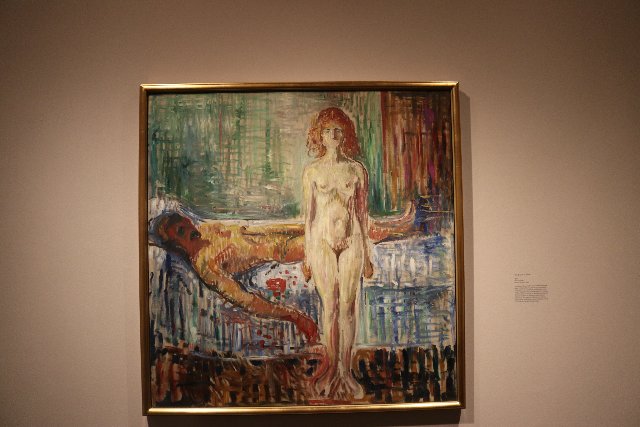

There is the fascinating 1894 painting Puberty. Just what was the relationship between the artist and the cowering, vulnerable girl in a pose seemingly protecting herself. There is a theme in the work, particularly in prints, of the artist as victim suffering abuses from women. Is that a self portrait as murdered, lying dead on a bed, with a bloodied woman seated next to him sketchily depicted in Death of Marat (1907)? It is very different from the painting of Marat in his bathtub by David in Brussels.

What is behind the dark and wrenching Weeping Nude (1913-1914)? Has the artist put her into this state? There are images of the clothed artist and nude model. In Artist and Model (1919-21) we know that she is Annie Fjedlbu. There are similar paintings by the German expressionist Kirchner.

The women who posed nude for the French impressionists were often their mistresses. Victorine Meurant, who posed for Manet’s Olympia learned enough in the studio to pursue a minor career as an artist.

In the current zeitgeist of sexual politics where to place the work of Munch? His images of illness, torment and angst evoke empathy. Is it best to focus on the strength and integrity of the oeuvre? Do we give Munch a free pass?

That leads back to the range and conundrum of the selection of 16 self portraits. They allow us to see how the artist viewed himself at various stages of his life and career.

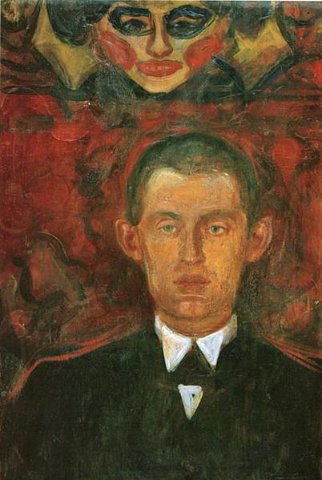

He photographed himself standing naked in the garden of his summer house in Åsgårdstrand in the summer of 1903. It is regarded as a study for Self Portrait in Hell from the same year. The apprehensive figure is lit from below creating an ominous scumbled shadow. The young man is handsome but depicted as damned and tormented by demons.

There is the earlier Self Portrait with Cigarette from 1895. It is similar in treatment of artificial light and evocative shadows. What happened in the eight years between that evolved to feeling himself damned? There is an interesting tradition of smokers in art from the Dutch masters Adriaen Brouwer and Jan Steen, the iconic self portrait by Max Beckmann at Harvard, or images by New York School painter Philip Guston.

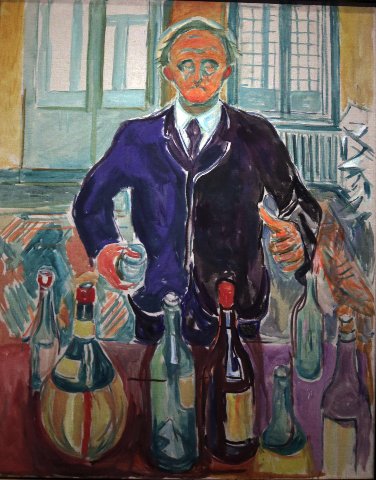

Looking at the range of self portraits one extracts the evolution of despair. There is an early one with a bottle and then, from 1938, a whole bunch of bottles signifying his alcoholism. Later works address insomnia and the cycle of drinking as self medication.

This complex torsion ratchets up to the magnificent, galvanic masterpiece Self Portrait: Between the Clock and the Bed. The application of paint is thin, sketchy and evocative. There is no concession to rendering and naturalism. He has a story or poem to evoke and spares us the details. We don’t know the time on the clock and his features are more implied than explicit. The symbolism is that of an aging and infirm artist caught between a rock and a hard place. In this instance, clock as time and mortality, and bed as rest and grave. It is a harrowing work as powerful as anything he produced. The curators were brilliant in keying off of it.

Writing about this work invades and haunts me. It underscores the passion, conviction, and courage of the artist depicting the suffering in his life and makes me think of my own.