Aspect Re-Introduces Arensky and Taneyev

Superb Chamber Music in Tchaikovsky's Shadow

By: Susan Hall - Feb 08, 2018

Philippe Quint, the superb first violinist of the musicians gathered to perform Anton Arensky and Sergie Taneyev chamber music, declared that the 21st century may well recover these two Russian composers to their rightful place in concert programming.

These composers, in Tchaikovsky’s shadow are spotlighted in Sergei Taneyev’s Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 30 and Anton Arensky’s String Quartet No. 2 in A minor. The program conceived by Quint and performed by him together with violinist Ji in Yang, pianist Alexander Kobrin, violist Milena Pajaro van de Stadt, and cellists Zlatomir Fung and Brook Speltz, was superb.

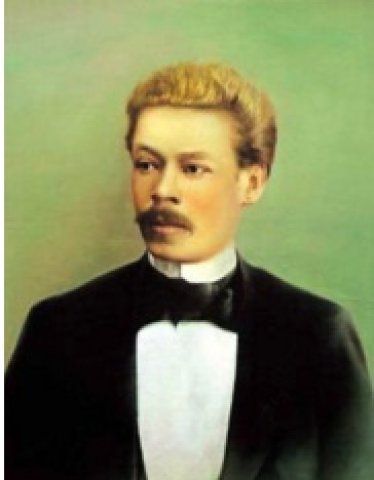

The names around Anton Arensky and Sergei Taneyev are more familiar than their own. Yet these composers were well-regarded in the early 20th century. Arensky was a student of Rimsky-Korsakov at St. Petersburg Conservatory and later taught at the Conservatory in Moscow, where his pupils included Rachmaninov and Scriabin.

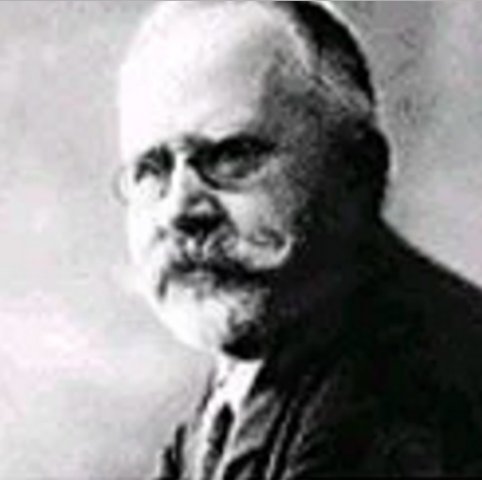

Taneyev started out as a talented pianist, who Tchaikovsky preferred as a performer of his own work. He too taught at the Moscow Conservatory for nearly 30 years, where his pupils also included Scriabin and Rachmaninov. Taneyev spent twenty years writing a fundamental work on counterpoint.

Arensky composed opera and orchestral music, but is most successful at chamber music. His Quartet in A Minor was performed in his unusual scoring of two cellos, a violin and viola. Seven sections followed one upon another. Sometimes there were repeated phrases, but never when you expected one. Phrases did not conclude, but hung in the air. A Russian hymn began the work and cropped up over and over to charm and delight. Arensky often brings a smile. The pizzicati pluckings are sweet and the mix of textures tantallizing. He was a pleasure to hear, especially in the hands of the superb artists who were performing.

The Taneyev was weightier business. It is scored for the conventional strings and piano. While the piano starts the piece off, it is almost like an offering and hovers in the background before it takes off. The strings take on an orchestral texture, perhaps because notes are double stopped on each instrument. On second hearing, it is clear that Taneyev's take on counterpoint also adds to the heft. Lines are by no means fugal, but rather mounted on each other. The voice of each instrument remains singular, but the effect is huge. Tanyev had concluded that ever more elaborate harmonies were dragging music down, and this lead him to the layering of melody. While there may not be a memorable tune in the piece, there is glory in its architecture which often yields up huge, carefully constructed bundles of notes.

Stravinsky admired Taneyev and like him would return to Bach's architecture as a model for composition.

WHile Tchaivkovsky and Taneyev were close, they were temperamental opposites. Tchaikovsky passionate and wild. Taneyev, formal, bound by erudite musical ideas into which emotions might be woven. Tchaikovsky teased that instead of becoming the Russian Bach, he might become a Russian Don Quixote, tilting like a windmill and driving the audience away. After hearing Tchaikovsky's 4th Symphony, Taneyev dismissed it as ballet music. "What's wrong with that?" the composer asked.

Aspect embeds its musical program in informative and often amusing background material. Wine is served before their events. Look for them at Italian House at Columbia next. As Quint pointed out, we might find a composer like Brahms, the Russian harmonist.