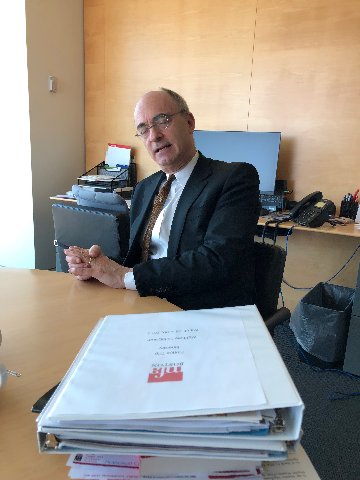

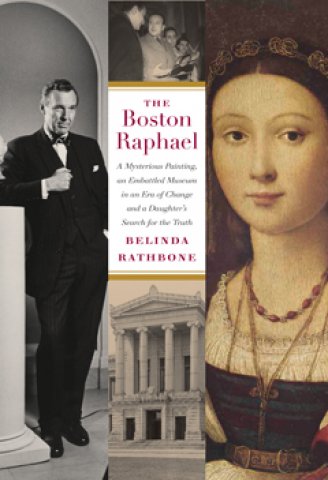

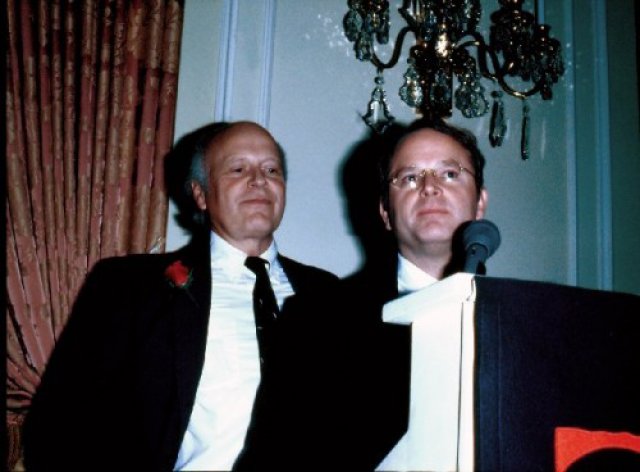

MFA Director Matthew Teitelbaum

Embracing Modern and Contemporary Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 20, 2019

In 2015 Matthew Teitelbaum became the 11th director of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Now 63, he brings a very different approach to the position than Malcolm Rogers who served for 21 years.

Best remembered for bricks and mortar, the mantra of Rogers was “One Museum.” That entailed house cleaning, the shake up and consolidation of departments. The exhibition program he promoted, primarily in modern and contemporary art, from cars to guitars, was populist and for critics primarily vulgarian. To his credit, with the new wing for Art of the Americas designed by Lord Norman Foster, Rogers left the museum in better shape than he found it.

If Rogers dominated the organizational flow chart, Teitelbaum speaks of bringing more seats to the table, reaching out for diversity and inclusion. He wants to shape an institution that is welcoming, non-elitist, and reflects the community it serves.

Before coming to the MFA, the British born Rogers, was a curator of 17th century British portraits. In the Canadian born Teitelbaum, for the first time, the museum has a director whose field is modern and contemporary art. Of America’s greatest museums this has been its most glaring area of weakness. He is making strong curatorial appointments and formulating strategies for change.

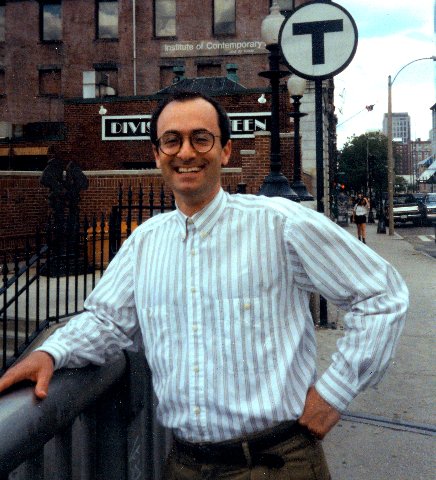

Teitelbaum was formerly a curator of Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art. He served as the Michael and Sonja Koerner Director and CEO of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. He holds a Bachelor of Arts with honors in Canadian history from Carleton University and a Master of Philosophy in modern European painting and sculpture from the Courtauld Institute of Art, London.

Charles Giuliano It’s been a long time.

Matthew Teitelbaum It was thirty years ago when we met. I joined the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in 1989 and was there until 1993 for three and a half years.

CG Did you come from the Courtauld Institute of Art? (Where he studied.)

MT No I came from a regional museum in Canada, The Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon.

CG Are you Canadian?

MT Yes, from Toronto.

CG From the ICA you returned to Canada and the AGO (Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto).

MT I came to Boston because my wife, to whom I was recently married, got a job in Boston. I left my job in Canada and came to live with her. Then I got a job at the ICA. I moved to Boston for love and then it worked out that I actually got a job.

CG I hope you have returned for love.

MT Yes, and then we went back to Toronto when I was asked if I would consider working at the AGO. It was my childhood museum and I started as chief curator. I was hired by Glen Lowry who then left to become director of MoMA. Max Andersen (Maxwell L. Andersen) came to be director of the museum. He left to become director of the Whitney (Museum of American Art). Then I became director. I was chief curator for just under five years.

CG Some years ago we visited the AGO and I recall its depth in sculpture by Henry Moore. Keeping up with you I understand that you made many changes.

MT (Laughing) Yes, I did. First of all I made physical changes. There was an expansion project with Frank Gehry. We did a building project with him. The collection changed somewhat through acquiring major collections that changed the narrative in the galleries.

I was thinking of this recently. When I left, I was there for sixteen years, I had hired all of the people. One way that you change a place is to hire people.

CG Talk to me about First Nations artists. Were you active in that area? Was that a part of the transition of AGO to be more inclusive?

MT Yes. I have had a personal interest and a professional interest in the art of First Nations people. I felt for a long time that their history was the history of Canadian art. Under my watch we acquired the first, historical, First Nations art ever. The museum hadn’t collected that material. We integrated First Nations art into displays of Canadian art on a consistent basis. I was very proud and pleased when we hired Gerald McMaster as the head of the Canadian Department. It was the first time a First Nations leader had been appointed to lead a department other than First Nations. The notion of putting his voice in the middle of development of history was very important to me.

(Gerald Raymond McMaster (born 9 March 1953, North Battleford ) is a Plains Cree and Blackfoot curator, artist, and author. He is enrolled in the Siksika First Nation . Currently he lives in Toronto and was curator of Canadian art at the Art Gallery of Ontario until 2012, when he was succeeded by Andrew Hunter.)

He and I worked together for just about four years.

CG I was fortunate to visit Montreal a number of times often invited by curators like Renee Blouin and Claude Gosselin to cover major exhibitions. The first time was essentially a tourism junket for travel writers promoting summer festivals. I asked if I might stay a bit longer at my own expense and extend the return flight.

The galleries I visited, based on the local gallery guide, were mostly commercial ones on Sherbrooke Street. By coincidence, that day there was an article about the Rene Blouin Gallery. After lunch I visited and was amazed. When I asked about other galleries he wrote down a number of alternative, government sponsored, Parallel galleries along Rue St. Laurent. I left Montreal with a very different overview than what was presented as part of the tourism package.

That summer, I returned with my mother. We got to know Rene and the galleries better as well as the museums. When Barbara Rose was editor of The Art Paper I wrote features on Canadian artists including Betty Goodwin. There was a major project in multiple museums and galleries in Montreal and Quebec City that Rene curated and I was invited to write about it.

It’s probably relatively unique that I have some interest and knowledge of contemporary Canadian art. Unfortunately, it’s been several years since we have visited although, from the Berkshires, it’s not a long drive. In general, the mainstream of American critics and curators have not paid close attention to our neighbors. When I ran the gallery program at Suffolk University, in 2002, I arranged a show of faculty members of New England School of Art and Design. Astrid and I drove the truck to Montreal and it was quite an adventure.

In the 1960s, when I lived in New York, I worked for the East Hampton Gallery. They represented several Canadian artists who had participated in The Responsive Eye which Bill Seitz curated for MoMA in 1956. We represented Guido Molinari, Claude Tousignant, and Jacques Hurtubise. They would drive down now and then to deliver new work. Marcel Barbeau was then living in New York so we saw a lot of him. I always respected their work particularly Molinari’s stripes and Tousignant’s circles.

Like much Canadian contemporary art they have been undervalued. Late in his career Molinari was represented by Blouin.

Considering Boston many of those problems may be applied here as well. I often state that the reputations of the best artists don’t extend beyond Route 128.

It’s well known that the MFA does not have a history of involvement with 20th century art. In 1971 Kenworth Moffett was appointed curator of twentieth century art. That was a milestone but Ken was narrowly focused on formalism.

In terms of modern and contemporary art the MFA is a mess and how are you going to clean it up?

MT I don’t know that it’s a mess but like all large institutions there needs to be some change. Very high on my priorities is to think about 20th and 21st century art. If we are going to continue to be a great encyclopedic museum we have to do better. It doesn’t mean that we haven’t enjoyed support or that great artists haven’t shown their work here. It means that we haven’t done it consistently enough.

I agree with what you’ve noted, which is that the museum needs to be more grounded in or connected to work in Boston. We’re thinking about how to do that. I believe that we should be a platform for artists who work here both historic and contemporary. We have to think about how to do that in a way that will have real impact.

The reality is that it isn’t just the lack of MFA support that leads artists to leave Boston. It also has to do with rentals and the cost of living. Boston is a really tough city to live in.

CG New York is more expensive.

MT It may not be more expensive. It may be the same with greater opportunity. It’s a very complicated thing. The reason why I say that all large institutions need to change is because we are also realizing that you take New York institutions out of that, because New York is a freak of nature. As someone said to me “New York is to the rest of the world as Picasso is to art.” It’s a freak and you can’t actually use it as an example.

Glen (Lowry MoMA) and Adam (Weinberg Whitney Museum) can just open their doors and they will get thousands of people. They get ten thousand people on a Saturday. It’s tourism and just the way those institutions are imbedded is fundamentally different from the MFA. Putting aside New York, all institutions have the same challenges. How do you express, which is part of our strategic planning, invitation and welcome? How do we say “You belong here come on in?” How do we make it a place that people want to go to? How do you make it friendly? How do you make it interesting? How do you make it less elitist? How do you make it more responsive? How do you make it more urgent? These are all things that we are talking about pretty actively.

I would hope that people who are following programming here see that there are shifts about how we are putting exhibitions together that marks a difference from the past. The question of how that reflects on collection building is slower. It’s not that there haven’t been adventurous and ambitious collectors of 20th century art in the 1930s and 1940s.

CG Can you name some?

MT There were a lot of people who did really great collecting in the ‘30s and ‘40s. There are a lot of great collectors today but they are mostly aligned with the ICA. The question is how does the MFA become a part of that dialogue? How do we have the platform that people want to be a part of? We’re talking about that.

CG You’re unique in the sense that you’ve had a foot in both institutions. You were a curator at the ICA and know it inside out. Now, amazingly, you are director of the MFA.

I want to comment that with this interview I have now interviewed every MFA director since Perry Rathbone.

MT Really. Including Perry.

CG My first job after college was in the Egyptian Department. I worked in the basement storage area. One day a guard came down and said “Mr. Rathbone has asked if you can turn down your radio.” It was lonely and I used to listen to the soul station WILD.

Perry was a museum director straight out of central casting. Belinda Rathbone interviewed me at length for the book on her father. (“The Boston Raphael,” 2014) The Raphael scandal was poorly handled by the trustees. Board chairman, George Seybolt, threw him under the bus.

Rathbone plays into the history of the ICA in an interesting way. At one point, during its many moves and transitions, the ICA was installed on the second floor of the Museum School. (In 1956)

Under its director Thomas Messer (February 9, 1920 – May 15, 2013) the plan was that the ICA would merge with the MFA as its contemporary department with Messer as its curator. At an ICA’s 50th anniversary event, during a press conference, I asked and Messer confirmed that. Nobody in the media knew what I was talking about. There is a transcript of a Messer interview that, in part, discusses his Boston years. It’s on line at the Archives of American Art.

When the ICA was on Soldier’s Field Road in Brighton he did important exhibitions. It was difficult to get there by public transportation. When I was in high school (graduated in 1959) I saw an Egon Schiele show there that I believe was the first in America. That went along with Boston’s well known interest in Germanic art.

Rathbone had different ideas, and while not a trained modernist, assumed it as his turf. He was joined in this by his friend, the curator of medieval art, Hans Swarzenski. Together they visited Picasso and bought the late “Rape of the Sabines” from his studio. Hans was also Perry’s “bag man” importing the alleged Raphael portrait of Eleanora Gonzaga in a ‘diplomatic’ pouch. With much fanfare, as Belinda reports in her excellent book, the painting was recovered by Italian authorities. When she asked to view it the painting was buried in the Ufizzi’s basement. As my former professor, Creighton Gilbert, wrote to me at the time it was heavily restored and not even a Raphael.

MT Did the ICA actually exist as such at the Museum School? Also, correct me if I’m wrong, but didn’t the ICA once exist in a fruit market? There was a period of time when the ICA had no physical presence and did exhibitions in a fruit market.

(In 1959 the ICA installed an exhibition at a Stop & Shop on Memorial Drive "Young Talent in New England.” This is a complex bit of ICA history. In 1968, at the end of the tenure of Sue Thurman, the ICA left space on Newbury Street at New England Life Hall. The content of the ICA, including an extensive library, was stored at its former site on Soldier’s Field Road. Under Drew Hyde, then working on Summerthing with new mayor Kevin White, he installed shows in various pop up spaces including a South End warehouse. He had access to a gallery in the new City Hall. Drew and I co-curated an exhibition on the new realism in that space. Eventually, the gallery was taken over as office space for City Councilors. The ICA went back to Soldier’s Field road and eventually moved to the mayoral mansion, The Parkman House, on Beacon Hill. Through Mayor White, Drew negotiated a lease on the abandoned police station on Boylston Street. From there, under current director Jill Medvedow, it built on the waterfront.

Another “fruit stall installation” was the ICA benefit staged as a part of the opening of the newly renovated Quincy Market. The ICA was known for raucous benefits and inventive locations. One memorable event “Fellini’s Basement” was held at Filene’s basement. That night, Bostonians were not so proper.)

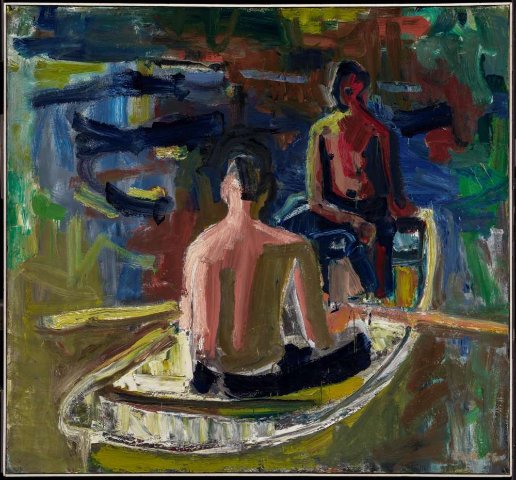

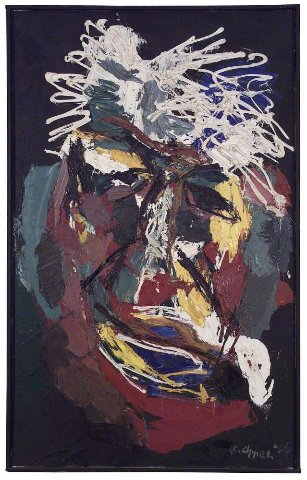

CG During Messer’s brief relationship with the MFA he advised on some acquisitions. They included a portrait of Willem Sandberg by Karel Appel and “Rowboat” (1958) by the former Bostonian and later Bay Area Figure artist David Park.

(The MFA information on the Park painting partly explains what transpired during this transitional period. “1959, sold by Stæmpfli Gallery, New York, to Mr. and Mrs. Stanley X. Housen, Boston; 1959, to the Institute of Contemporary Art (provisional collection), Boston; 1963, sold by the Institute of Contemporary Art to the MFA. Accession Date: December 11, 1963.” Funds for the purchase were provided by Lewis Cabot. Given the quality of these works, unique at the time, they evoke speculation on what might have been. Messer left to become director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.)

MT What’s interesting about that is that Perry Rathbone was a part of the group at Harvard that was very interested in modern art. (They were students of Paul Sachs, November 24, 1878 – February 18, 1965, an American Investor, businessman and museum director. He served as associate director of the Fogg Art Museum and as a partner in the financial firm Goldman Sachs.)

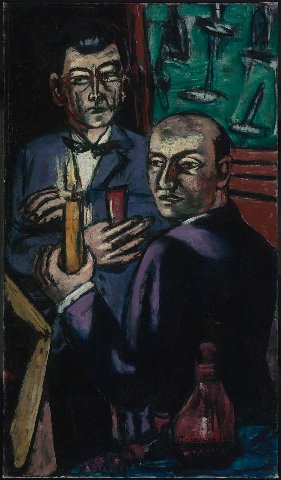

Rathbone had that sense that he could probably do it. (Curate and collect modern art for the MFA. He acquired works by his St. Louis friend, Max Beckmann, and examples of German expressionism and Edvard Munch.)

He probably wanted that space because he thought he could make it happen.

CG His curatorial partner was Hans Swarzenski who, while a medievalist, was connected to the German born art dealer Curt Valentin. Beckmann painted a double portrait of them that Swarzenski gave to the MFA.

I recall during the late 1950s and early 1960s that the modern/ contemporary gallery was next to the Fenway entrance. For a number years it featured on loan a muti-piece, bronze Picasso sculpture “The Bathers.” There was a large abstract painting “Rue Gauquet” by Nicolas De Stael (Russian/ French 1914-1955) as well as paintings by Fannie Hillsmith (1911-2007), Loren MacIver (1909-1998), Kenzo Okada (1902-1982) and Donald Stoltenberg (born 1927).

That’s what passed for modern/ contemporary art. When I commented to Rathbone about those works, he replied that they bought the De Stael for a few thousand dollars and that it was then worth many times that. (Current auction prices range from one to twelve million dollars.)

In recent years, there were media reports of antipathy between MFA director, Malcolm Rogers, and ICA director, Jill Medvedow. They were both in the midst of fundraising for expansion and new construction. Particularly in the fine arts, there are only so many deep pockets to call upon. Now that we are past the bricks and mortar phase I assume there are better relationships between the MFA and ICA. Is it possible one day to work together on exhibitions, acquisitions or projects?

MT When you’re never the big one. That’s to say that you’re not New York or Los Angeles, and you’re Boston, you’re still pretty big, but not the big one. And you want to compete; you have to think of all institutions as one thing, a whole. You have to think of The Gardner Museum, and the Harvard Art Museums. You have to think of us as a circle and we’re all inside the circle. I think, for sure, the ICA and MFA have to think of doing some projects together. I don’t think that includes collections.

CG Of course they collaborated on “BiNational.”

(A collaboration between the MFA, ICA, and German curators to create an international touring exhibition “BiNational” in 1988. The MFA director was Jan Fontein and its team included Amy Lighthill and Ted Stebbins. The ICA team was headed by director David Ross with curators Elisabeth Sussman and David Joselit. The German museums were Stadtische Kunsthalle Kunstsammiung Nordrhein-Westfallen and Kunstverein fur die Rheiniande und Westfallen, Dusseldorf.)

MT That was happening just as I was coming on board at the ICA.

Jill (Medvedow) and I respect each other, are comfortable with each other. I would say that we mutually admire the quality of what is being achieved at both of our institutions. We haven’t yet got to the point of joint programming. We have spoken about a couple of things but haven’t gotten any momentum behind them yet. I think in the end we will want to work together.

We are just putting together our contemporary department. Reto has only been here for six months.

(Formerly with The Cleveland Museum Reto Thüring will oversee programming—including special exhibitions and gallery installations throughout the building—from the contemporary art department, which was established in 1971 and comprises over 1,500 works of various mediums. Edward Saywell, who formerly chaired the department, has been promoted to the position of Chief of Exhibitions Strategy.)

Akili Tommasino, associate curator of modern and contemporary has been with us since October. (Previously Tommasino was at MoMA as a curatorial assistant.) We are just about to hire our crafts curator.

CG In doing research for a book I have been looking at the social and political aspects of art in Boston; particularly as it pertains to the MFA. There have been shows that celebrate the heritage.

(In 1969 “Back Bay Boston: The City as a Work of Art” with essays by Lewis Mumford and Walter Muir Whitehill. In 1975 “Paul Revere’s Boston: 1735 to 1818” curated by Jonathan Fairbanks with a Whitehill introduction and Carol Troyen’s traveling exhibition “The Boston Tradition” in 1980. In 1982 Fairbanks curated “New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century.” Trevor J. Fairbrother curated “The Bostonians: Painters of an Elegant Age, 1870-1930” in 1986. Then, in 2001, Erica E. Hirschler curated “A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston 1870-1940.”)

It is significant that the MFA stopped celebrating Boston artist after 1930, in the Fairbrother show, and up to 1940 in Hirschler’s project. Those cutoff dates are hardly arbitrary. The 1930s is precisely when the mainstream of the Boston art world transitioned from “elegant” and genteel to Jewish. The leading artists were the Boston Expressionists. Jack Levine and Hyman Bloom were South End residents and sons of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. Karl Zerbe was born in Germany. The Lebanese poet and artist, Kahlil Gibran, lived in the dominantly ethnic South End. The Brahmin MFA shunned these artists who are still inadequately represented in the MFA’s collection and programming.

Major works by Bloom and Zerbe were acquired through the William H. and Saundra B. Lane collection. I understand that Hirschler is planning a small Bloom show.

Some years ago, I wrote a cover story for Boston After Dark/ Phoenix about a paradigm shift of leadership at the MFA and issues of anti Semitism. It is well established that Boston has a history of racism. The resistance against school bussing to achieve integration was an example. When did the museum begin to have Jewish trustees?

My understanding was that the old money ran dry. To attract new money changes were in order. Sitting in your seat how does the museum address historical problems? In addition to non inclusion of Boston’s Jewish artists are related issues related to African American artists. Looking at galleries in the Art of the Americas wing Native American culture is poorly represented. Historical artifacts are jammed in with a hint of contemporary artists like a small work by Jaune Quick to See Smith. There is a need for the museum to reflect the diversity of its citizens. Touring the country we see that many museums have taken strides to address issues of representation and balance in their collections.

In 1968, activists like Dana Chandler, Jr. knocked on the door and reminded the museum of its proximity to Roxbury. That’s when Barry Gaither was appointed adjunct curator of the MFA while also director of the National Center for African American Artists. In 1970 he organized a major exhibition “Afro American Artists New York and Boston.” He went on to curate a number of important shows.

(The MFA in 2011 acquired 67 works by African-American artists from museum benefactor John Axelrod, a retired attorney and former trustee who oversaw the MFA’s diversity advisory committee. He sold the works to the MFA for between $5 million and $10 million, then well below market rate.)

MT I think you put your finger on it. It goes back to the notion that I believe that institutions have to be more open and accessible. That is the future and it goes to exactly what you said. Which is, that our audiences are themselves diverse. Our audiences bring different life experiences. Once that you acknowledge that, you want to expand, and want to be an institution for your city, then that notion leads you to different community leaders. You then have to invite them into the work of the institution. Which is why boards start to diversify.

I don’t know, per se, that money dried up. Or enthusiasm.

CG If I may insert an observation, because I was a witness at the time, it was a fallow period. The museum had lost momentum. There was a reduction of galleries on view in rotation. The Fenway entrance was closed as an economic decision. There was a need for renovation and change including climate control of the painting galleries. Major traveling shows were bypassing Boston including the Tutankhamun show. Given the importance of the MFA’s Egyptian Collection that was a major blow. All of that expressed a need for new revenue. That called for a paradigm shift.

MT For whatever reason, and we could talk about that, there was a lack of risk taking.

CG In 1970 there was an ad hoc policy report that defined mandates for the future. One resulted in hiring Ken Moffett. Initially, he was part time while a professor at Wellesley College. There were few resources to support his programming and acquisitions. Overall, in the final phase of Perry Rathbone as director, there was a low point for the museum. The unilateral appointment of Merrill Rueppel (1973-1975) by Seybolt derailed. A palace revolt was reported in the Sunday Globe by Robert Taylor with more promised. He was gone that week. Jan Fontein, curator of Asiatic art, was made acting director and later permanent director. His tenure proved to be problematic.

MT I’m fascinated by what you are saying. It’s true to some degree. At some point when institutions need to open their arms wider it narrows ideologically. So when they set up a contemporary department it was an ideologically driven contemporary department. It was relatively narrow in scope. It’s exactly the opposite statement you want to make about contemporary art.

CG Ken did a lot of good things.

MT He sure did and he left a legacy in terms of his collection. It would be very hard for anybody to argue that his collection and commitment reflected the broad engagement of artists with the ideas of contemporary art, making of contemporary art, and critical discourse about contemporary art, not just in New York, but in Boston itself. In some degrees it was an exclusionary practice.

CG He was involved with formalism which was the focus of the trustee Lewis Cabot who backed him. It is what he collected and was known at times to deal in. Allegedly, with Cabot there were levels of conflict of interest. But I would not accuse Ken of that. To me he was always a gentleman and a scholar with a true passion for the artists he promoted and believed in. I had many discussions of that with him. After the MFA he became director of the Fort Lauderdale Museum of Art. When visiting my mom for holidays in Palm Beach I would have lunch with Ken.

MT I think there is a simple truth that leads to greater diversity. It goes as follows. We have leadership in the institution that understands it. Complex times need diverse points of view. It’s a very simple truth. It exists at the staff level as much as it exists at the board level. We’re starting to open up dialogues and inviting more points of view. It comes from the idea that we need some good problem solving skills to get through some of these issues. How are we going to get there? By having more points of view around the table.

While your historical observations may very well be true. You say that you have done the research. I would say that’s not the feeling at the MFA today. The question is how do you actually achieve it? Allow us five years to look at the board and the staff and say, yes, there has been a change. We’re still working that through. Conversations we’re having, people are telling me, they’re fundamentally different then they were before.

CG The MFA seems reluctant to celebrate itself. Because of its puritanical traditions Boston doesn’t seem comfortable with blowing its own horn. We were in San Francisco in 2017 for the fiftieth anniversary of The Summer of Love. There were many celebrations including a stunning museum exhibition. It included all of the hippie culture from rock bands, posters and costumes, film and photography. It was a very successful project. There is a new documentary film by Bill Lichtenstein “WBCN: The American Revolution.” Viking press has published the well reviewed book by Ryan Walsh “Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968.” The Lichtenstein film takes the approach that in 1968 the counter culture shifted to Boston with a mandate for social and political activism. I am writing a book “Counter Culture in Boston: 1968 to 1980s.”

That period was a time of enormous change for Boston. The ICA more or less died in 1968. It was forced out of Newbury Street and its material was put into storage in its former home on Soldier’s Field Road. Drew Hyde was working with Kevin White and Summerthing. With the backing of Kathy and Lewis Kane, she worked for the Mayor, Drew became acting director and slowly revived the moribund ICA. There was a proliferation of media and emergence major rock bands.

Through a number of projects there is new attention to the unique role of this golden age. Shouldn’t the MFA be a natural platform in celebration and education? It is interesting that there is a current MFA video installation focused on aspects of the Black Panther Party in Boston at that time. That’s a glimpse of a larger picture of major social and political change including the National Student Strike and Moratorium that started on Boston Common. The MFA doesn’t appear to be interested in that counter culture history.

(“Bouchra Khalili: Poets and Witnesses.” Charting the essential connection between poetry and activism, an exhibition of works by Berlin-based artist Bouchra Khalili (Moroccan, b. 1975) bridges discourses of resistance from the 1960s to the present. Making its US debut at the MFA, Khalili’s “Twenty-Two Hours” (2018) is a testament to her deep research into the Black Panther Party in New England and their unexpected ally, the French poet Jean Genet.

In 1970, Genet toured the US in support of the Panthers, delivering his first speech in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Khalili recently completed a fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. In “Twenty-Two Hours,” two young Bostonians, Quiana Pontes and Vanessa Silva, perform on camera in Cambridge, combining fragments of images, sounds, memories, and film footage to retell the story of Genet’s visit and reflect on the civic poet as a witness to history.)

MT One of our priorities, and I think about it a lot, is to celebrate Boston. It’s not the way the institution has thought. I think you’re right to mention something about Puritanism. That notion of propriety and not drawing attention to yourself. I get that. On the other hand there are a lot of hidden histories that would make us feel better about ourselves. I would even say something more strongly. Knowing that history will change some of the conversations here today.

CG Who will change that?

MT You and other people who are going to write it. Then whether institutions get involved in some way. Celebrating the complexity of what happened here.

CG Will you read those books?

(There is a bibliography of some thirty books, past and recent, about media, jazz, rock and folk music in Boston and Cambridge from the 1950s through the present. For further research there are growing archives. Northeastern University has the Stephen Mindich Boston Phoenix collection and Kay Bourne’s Bay State Banner documents. The David Bieber archive has a million items and U Mass Amherst is a major and growing resource.)

MT I think it’s really important to know where you are.

CG I urge you to see the WBCN documentary. You were here at that time but may not have participated that much being married and such.

MT I was completely square. (Both laughing) But recognizing that I am interested in how understanding our past generates understanding of our present; in terms of energy and possibilities. Knowing more about that would be really, really powerful.

CG The ICA was adamant about its position as a kunsthalle (non collecting museum). Just imagine if from those shows they acquired one or two pieces over the years.

MT I look at it differently and here I am a little tough on the MFA. I’m not so sure that the ICA should have been collecting then. But the MFA should have been buying out of every show. Can you imagine today what a collection it would have? That’s if we see ourselves as one institution. Now we can’t do that. They do what they do and we do what we do. At the time I often thought about that. (When he was with the ICA.)

CG What do you do about the 20th century? Is that gone and just too expensive?

MT Yes, if you buy. But it’s not too expensive if you can find a way to create a home for great collections.

CG What made the MFA great was that Bostonians were collecting impressionism and post impressionism during a time when Parisians weren’t.

MT They also had the support of collectors who were interested in having that happen. It was the MFA collecting and the community collecting. Now we have the community collecting but we’re not in the mainstream with those collectors in the way that the ICA is.