Pollock's Masterpiece Lavender Mist

How It Got Away From the MFA

By: Charles Giuliano - May 05, 2024

During a recent Sunday afternoon at the National Gallery we viewed the exhibition of Mark Rothko’s drawings. It was a riveting experience with much that was new to absorb.

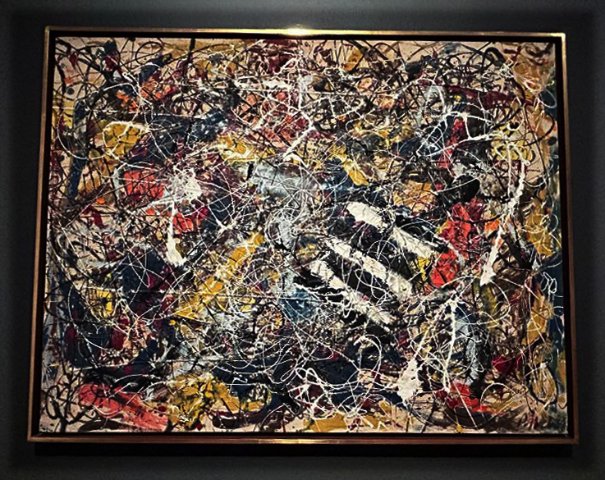

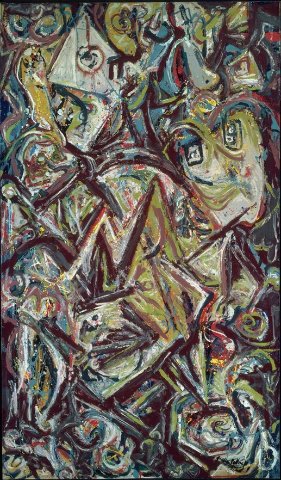

Moving on to the Twentieth Century collection we encountered the familiar Jackson Pollock masterpiece, Number 1, 1950, which with the artist’s approval, was named Lavender Mist by the art historian, king-maker and critic, Clement Greenberg.

Standing before the work, created during his “drip period,” from 1947 through 1951, yet again I felt absorbed into the large work following its intricate and delicate tracery of layered skeins of color. There is actually no lavender paint but, as Greenberg saw it, a miasma that evokes a shimmering sensation. The work is less than static as it dances before us just as Pollock did in an elaborate choreography of creating it.

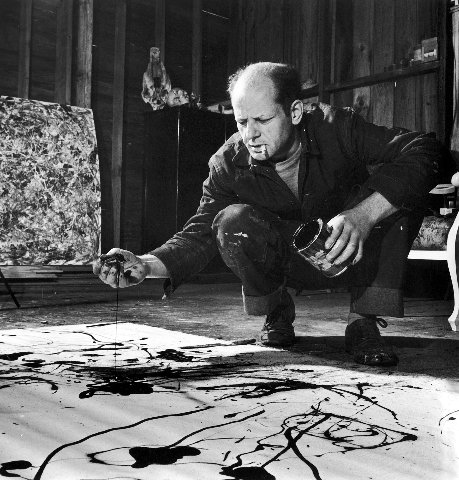

During this period he spread canvas on the floor and worked all around from the edges splattering paint with sticks, stiff brushes and turkey basters. This process was called Action Painting by critic Harold Rosenberg who, with Greenberg, dominated critical thinking of their era.

Speaking of this process Pollock (January 28, 1912 – August 11, 1956), stated, ‘”My painting does not come from the easel. I prefer to tack the unstretched canvas to the hard wall or the floor. I need the resistance of a hard surface. On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting…

“When I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It is only after a sort of ‘get acquainted’ period that I see what I have been about. I have no fear of making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through. It is only when I lose contact with the painting that the result is a mess. Otherwise there is pure harmony, an easy give and take, and the painting comes out well.”

Like other artists of the New York School he barely got by. He had the patronage of Peggy Guggenheim who paid a stipend and loaned the down payment for a house and barn at Springs, Long Island. He moved there with his artist wife, Lee Krasner, when they married in 1945. In relative isolation he developed the drip paintings. As his widow she shrewdly managed the estate and created the Pollock/ Krasner Foundation which offers grants to artists.

There was a dismal response and no sales when drip paintings were shown in 1948. That changed following an August 8, 1949 four-page spread in Life magazine that asked, “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” At the peak of his fame, Pollock abandoned the drip style.

Enduring the Depression and post war years, like many of his generation, he struggled with inner demons and alcoholism. From 1938 through 1941 Pollock underwent Jungian psychotherapy with Dr. Joseph Henderson and later with Dr. Violet Staub de Laszlo in 1941-1942. Jungian concepts informed his work.

Dr. Henderson, who practiced a mélange of techniques derived from Freud and Jung, encountered a withdrawn and difficult patient. He suggested that the artist create drawings which were discussed in therapy sessions. A portfolio of these drawings was later consigned to Boston gallerist Nina Nielsen. She approached but was unable to sell the collection to a museum. With no alternative these fascinating works were sold individually.

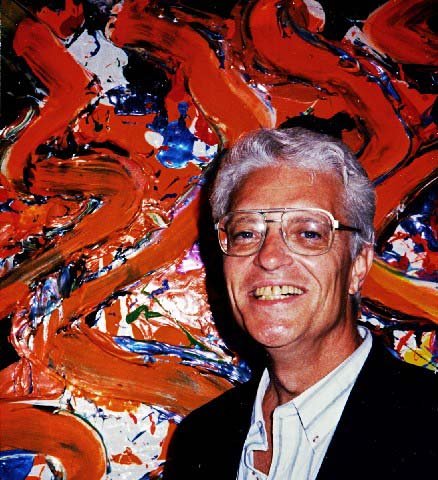

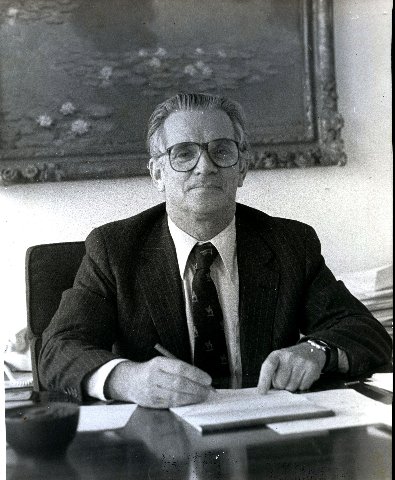

The Museum of Fine Arts passed on the opportunity as they had previously when offered Lavender Mist in 1976. It was the fifth year of founding contemporary curator Kenworth Moffett ((born 1934 in East Orange, New Jersey – June 21, 2016). He was appointed as one of the last acts of director Perry T. Rathbone, who following the “Raphael Incident,” was forced out by Board President, George Seybolt.

When the decision to collect contemporary art was made, trustee Lewis Cabot, a collector, art consultant, and trader of formalism, lobbied for the appointment of Moffett, a protégée of Greenberg. Dr. Moffett was then a full professor of art history at Wellesley College.

Although he founded a department, initially, with little more than a desk, secretary and no budget, he worked part time. Eventually, he organized exhibitions of sculptor Anthony Caro, painters Jules Olitski, Barnett Newman, Friedel Dzubas, and the first museum show of the realist Albert York as well as Horacio Torres. Moffett co-authored a monograph on Fairfield Porter, A Realist Painter in the Age of Abstraction with John Ashbery, among others, to accompany the 1983 Porter retrospective. During his 13 years at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, he oversaw the bequest of 26 paintings by Morris Louis, as well as acquisitions of over one hundred artworks, including paintings by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Joan Miró, Hans Hofmann, Jackson Pollock, and Helen Frankenthaler.

When the museum was undergoing renovation Moffett became director of a temporary space at Quincy Market. Supplementing his own programming he invited guest curators, Christopher Cook (Douglas Heubler) and John Arthur (Richard Estes and Alfred Leslie). Anthony Caro’s York Series of steel sculptures were displayed on the expansive lawn in front of the Christian Science Church. Overall, his programming was effective while limited in scope. Jules Olitski, for example, was given two exhibitions; one for painting, and the other for sculpture.

The cutting edge of American art changed radically during his tenure and Moffett did his best to avoid what he saw as trends. During the same period the Metropolitan Museum of Art created a contemporary department with Henry Geldzahler as curator. He was well connected with New York artists who were featured and collected by the Met.

Geldzahler’s time at the Met is remembered for the 1969 exhibition, New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970. It was the Museum’s first exhibition of contemporary American art and marked both the inauguration of the newly established department of Contemporary Arts and the 100th anniversary of the Museum.

The exhibition featured 408 works in 35 galleries, by 43 artists including Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, Frank Stella, David Smith, Jasper Johns, Mark Rothko, Andy Warhol, and Robert Rauschenberg.

Moffett had different taste and interests but Morris Louis and the formalists that he favored have lost their luster. The MFA displays some of this work but moved on with other curators and visions. Overall, of the major American museums, its collections of modern and contemporary art are underwhelming.

The museum today, under Matthew Teitelbaum, is making every effort within its means to address these issues. He started as a curator for the Institute of Contemporary Art before evolving as director of the Art Gallery of Ontario. In Toronto he pioneered representation for First Nations artists. Developing the First Nations, Inuit and Metis art collection is one of the AGO’s primary collecting goals spanning several centuries. He has brought that innovative approach to the MFA,

Think how differently we might view the Moffett legacy had he succeeded in nailing down Lavender Mist. Its potential acquisition proved to be a fiasco and pratfall.

After being nudged out of the MFA by curator of American art, Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., Moffett became director of the Fort Lauderdale Museum. During annual holiday visits with my Mom in Palm Beach I would meet Ken for lunch.

Away from turmoil in Boston he thrived. The museum was eclectic and diverse. During visits I enjoyed exhibitions of Nam June Paik and Fernando Botero. His curators were given latitude while Moffett focused on development and administration.

Ken was a scholar and gentleman and I much enjoyed our discussions and debates. He laid out for me the Lavender Mist fiasco.

He convinced the artist and collector Alfonso Angel Yangco Ossorio (August 2, 1916 – December 5, 1990) to sell the painting for a price alleged to be south of a million dollars. Ossorio was a neighbor and friend of Pollock and acquired work which greatly influenced his own style of surreal abstraction. In New York during the 1960s I recall his exhibitions of assemblages at Cordier Ekstrom Gallery.

It was quite a coup for Moffett to pry loose one of Pollock’s greatest works. Ken related the lively story of picking up the painting and escorting it to the MFA where it was installed in the trustee’s room.

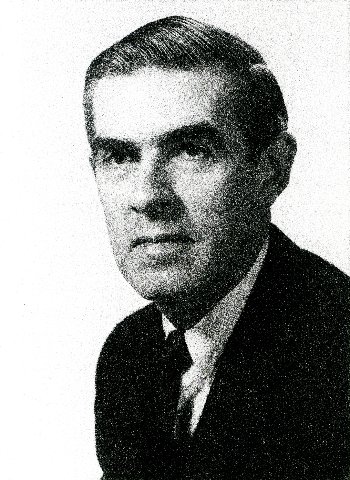

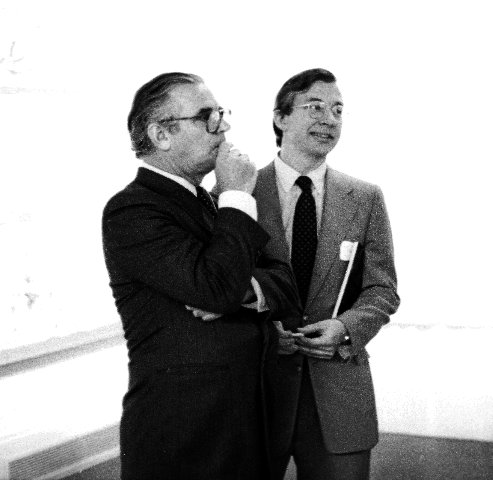

The curator made his presentation to the committee. According to Ken, someone said “We should get the new guy in on this.” That meant the director Merrill Rueppel (1925-2011). Recruited unilaterally by George Seybolt from the Dallas Museum of Art he replaced interim director Cornelius Vermeule who was also a candidate. There were disjunction and leadership issues following the ouster of Rathbone.

Asked for his opinion of the Pollock, Rueppel raised conservation questions. What happened if some of the paint fell off? That entailed a call to chief conservator William Young. After examining the work Young reported that he hadn’t a clue how to restore such a painting.

That nixed the sale. The trustees turned down a deal for what was then seen as a lot of money for a painting they were clueless how to conserve and potentially restore. Within weeks the trustees of the National Gallery had no such misgivings.

The Pollock incident was the first of many for the soon doomed Rueppel. A cabal of curators leaked their misgiving to the Globe. Stoked by talk of a Pulitzer a team of reporters were egged on to write an expose. Not satisfied with a final draft it was rewritten by Globe editor Tom Winship. The piece ran as part one on Sunday but that was it. Rueppel was fired that Monday before the second installment was published.

Standing in front of arguably the greatest single abstract expressionist painting of its generation its irony overwhelmed me. It is the linchpin that solidifies the great collection of the National Gallery. The museum also owns Number 7, 1951, black paint on unprimed canvas with lines and figuration; as well as Ritual, 1953, a vertical painting divided into three tilting zones.

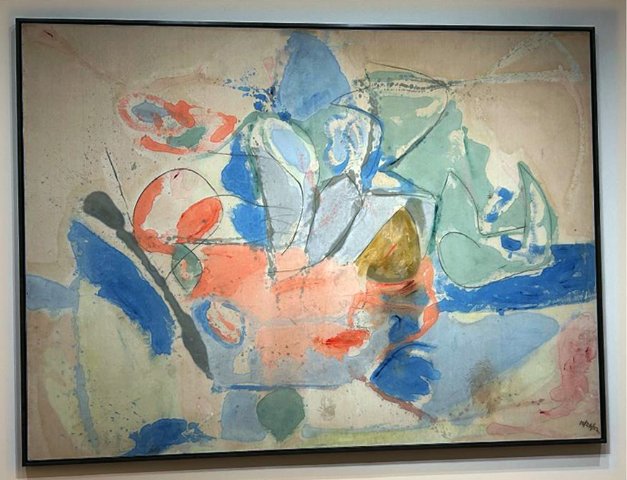

Just steps away we encountered Mountains and Sea, 1952, by Helen Frankenthaler. Then just 23, the graduate of Bennington College was involved with Greenberg. Stained into unprimed canvas it was the breakthrough to the question of what comes after Pollock? It influenced the launch of the Washington, D.C. color field painters Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland. Other works from Frankenthaler in the 1950s were curated by Carl Belz for the Rose Art Museum.

There is a trajectory as the work of Pollock evolved from the initial influence of regionalist Thomas Hart Benson through ever more abstract figuration. The Jungian period is of great interest. The Triumph of American Painting, as Irving Sandler put it, solidified with Pollock’s unique, monumentally scaled, drip paintings.

At Pollock’s funeral de Kooning stated “Pollock broke the ice.”

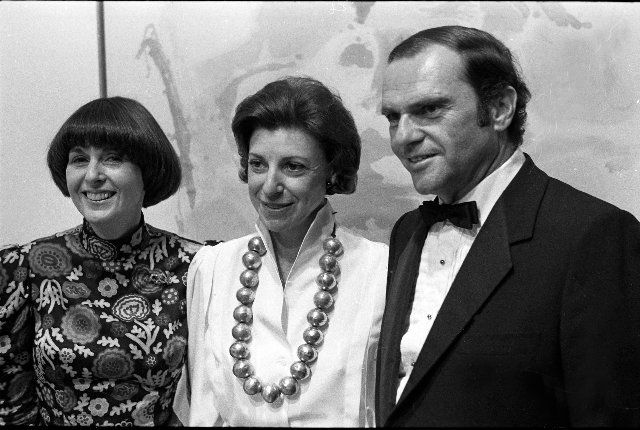

Astrid in front of Lavender Mist, National Gallery.

1234567891011121314151617181920212223

How did that happen? There is great interest in the dissection of origin facts and legends. During WWII the surrealists were in New York led by Andre Breton and supported by Peggy Guggenheim and her innovative Art of This Century gallery. One important branch of surrealism was automatism. Joan Miro and Max Ernst are discussed as influences as well as Andre Masson. Arshile Gorky was fully encamped with the surrealists. Mythology suggests that young Pollock saw Indian sand painting.

There is renewed interest in the experimental work of Janet Sobel (May 31, 1893 – November 11, 1968), a Ukrainian-born American Abstract Expressionist painter. Her career started mid-life, at age forty-five in 1938. By 1943 Sidney Janis included her in a group show. Most significantly she was embraced by Guggenheim. Her mercurial rise ended when Guggenheim closed the gallery after the war and the artist relocated to the hinterlands of New Jersey.

Guggenheim included her in the important group show “The Women” in 1945, which included Louise Bourgeois, Lee Krasner, Leonora Carrington and others. She was shown in the Brooklyn Museum’s annual juried exhibition three years in a row, from 1943 to 1945. She was given a solo show by Guggenheim with a catalogue essay by Sidney Janis.

She is credited with inventing the drip style which is the focus of “Janet Sobel: All-Over,” an exhibition now on view at the Menil Collection in Houston. It is the first major museum survey dedicated to Sobel’s career.

In 1944 Sobel had her first solo show at New York’s Puma Gallery, which Clement Greenberg visited with Pollock. In an update to his essay “American-Type Painting,” Greenberg wrote that they “admired these pictures rather furtively,” adding: “Later on, Pollock admitted that these pictures had made an impression on him.”

The end of Pollock’s drip paintings was traumatic. His studio process was documented by Hans Namuth. The photographer prevailed on the artist to create a work on glass. A camera was mounted below to record the action. There are similar films of Picasso at work. The Namuth session did not go well as we see in a You Tube video.

Working on glass for the first time Pollock announces that he “lost contact” with the painting. With a turpentine rag he erased it and started over.

The event was followed by an intimate dinner party, during which, Pollock became enraged and overturned the table. He grabbed a bottle of booze stashed under the sink and went on a bender which lasted off and on for the rest of his life. In the final year he stopped working.

Just after 10 p.m. on August 11, 1956, Pollock, who had been drinking, crashed his car into a tree less than a mile from his home. Ruth Kligman, his girlfriend at the time, was thrown from the car and survived. Another passenger, Edith Metzger, was killed, and Pollock was hurled 50 feet into the air and hit a birch tree. He died immediately.

In December 1956, he was given a memorial retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art and a larger more comprehensive exhibition there in 1967. More recently, in 1998 and 1999, his work was honored with large-scale retrospective exhibitions at MoMA and at The Tate in London.

With time the aesthetic and monetary value of Pollock has soared. We were surprised to encounter two works by Pollock during a recent visit to the Norton Museum in Palm Beach.

Billionaire art collector Ken Griffin has moved several of his most high-profile artworks from the Art Institute of Chicago, where he is a trustee, to the Norton. These included Mark Rothko’s No. 2 (Blue, Red and Green), 1953, Roy Lichtenstein’s Ohhh…Alright… (1964), an untitled Robert Ryman, Willem de Kooning’s Interchange, and Pollock’s Number 17-A. The museum also owns Night Mist, 1944-45, by Pollock

Griffin bought the de Kooning from David Geffen for $300 million, and the Pollock for $200 million. Both of these works were also displayed at the Art Institute. The news of the relocated artworks follows the move to Miami by Griffin’s hedge fund Citadel. Over the past decade he has spent some $350 million on property in Palm Beach.

Consider the issue of evaluation. In 1973 the National Gallery of Australia purchased Pollock’s Blue Poles, also known as Number 11, 1952. It paid $1.3 million and needed government approval for a purchase over one million.

Its first owners Fred and Florence Olsen paid $8,000. In 1957 it was sold to Ben Heller for $32,000. Considering the $200 million paid by Griffin for a lesser Pollock, what are masterpieces like Lavender Mist and Blue Poles worth today?

While the MFA blew its chance at Pollock’s masterpiece in 1971 Moffett cajoled another work from Ossorio, Pollock’s Number 10, 1949. A wide and narrow painting in the drip style, Moffett maintained that it was a significant acquisition.

In 1984 the museum moved on another Pollock, Troubled Queen, 1945, a large, vertical, transitional work with a combination of figuration and abstraction executed with brush and drip. The director, Jan Fontein, an orientalist, deferred to the authority of Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. who then had uniquely broad power over painting acquisitions.

Upon first encountering it hanging in the museum I was intrigued by its label which stated “Charles H. Bayley picture and painting fund and museum purchase with funds by exchange from the gift of Mrs. Alfred J. Beveridge and the Juliana Cheney Edwards collection.”

I did some sleuthing and connected the dots. The relatively young contemporary department lacked endowment. But serendipitously, during a small window of time, Stebbins was the fox guarding the chicken coop of the European painting collection. There was no senior curator on staff to object when with legerdemain he swapped two Renoirs and a Monet for a Pollock. In museum parlance that’s apples for oranges.

As he later explained to me they were rarely displayed minor works in exchange for a major Pollock. But this doesn’t trump the museum mantra of trading like-for-like when upgrading collections. At the time Renoir’s Girl with a Red Bonnet was a top selling museum post card,

I was reporting on the acquisition for my editor Jon Lehman at the Patriot Ledger. In the afternoon when we were going to press there was a call from MFA PR director, Clementine Brown.

She asked what I was up to and I requested confirmation of our facts. She said that she would get back to us but never did. The next day the story ran in the Globe. We protested and that Sunday the Globe ran an editorial that acknowledged it was our story which ran a day late and dollar short.

Since then I have been reluctant to make those last minute confirmation calls. Clementine later apologized saying that Jan stood over her insisting that she call the Globe.