Boston Expressionists Rehung at the MFA

A Major Exhibition of Hyman Bloom is Scheduled

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 06, 2018

There have been changes at the Museum of Fine Arts to installations of modern and contemporary art as well as in the Art of the Americas Wing.

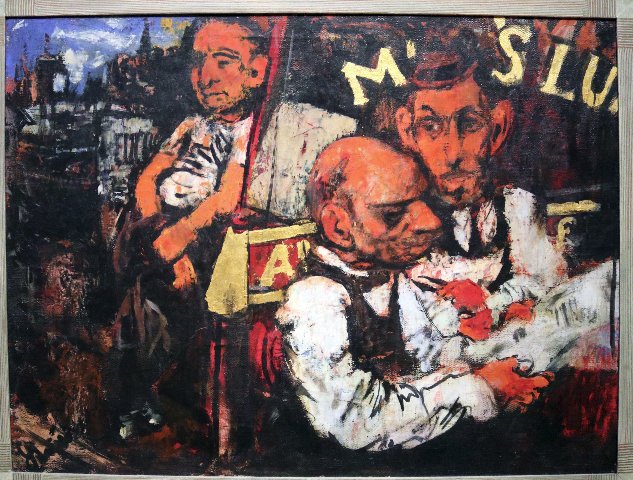

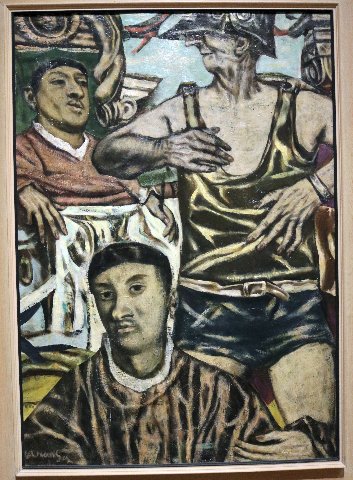

In particular, there is a gallery conflating the German Expressionist painter Max Beckmann (1884-1950) with examples by the primary Boston Expressionist artists Hyman Bloom (Born Latvia, 1913-2009), Jack Levine (Born to Lithuanian parents 1915-2010) and Karl Zerbe (Born Germany, 1903-1972). The next generation was represented by David Aronson (1923-2015). Missing most prominently were Arthur Polonsky (Born 1925 and still active) as well as Henry Schwartz (1927-2009).

There have been exhibitions of these artists at the Danforth Museum, DeCordova Museum, and former Fuller Museum of Art. A number of articles and books have discussed the three founders as well as the second and third generations they inspired. Of America’s major arts communities Boston is unique in its commitment to expressionism and figuration.

The reputations of even the best artists generally don’t reach beyond Boston. Mustering out of the military in the 1940s, Levine relocated to New York where he continued to root for the Red Sox.

As teenagers Levine and Bloom were discovered and groomed by Harold Zimmerman who taught art classes in a South End settlement house. He introduced them to Denman Ross, a Harvard professor, who offered them stipends to focus on his art classes. In addition to composition and schematic design (Jay Hambridge’s Dynamic Symmetry) he taught them to draw from imagination.

He sent them to the BSO then assigned them to draw its musicians from memory. When David Sutherland was making a documentary film "Jack Levine Feast of Pure Reason" we spent an afternoon at the Fogg Art Museum, with curator Agnes Mongan. We went through boxes of their juvenilia. I admired Levine’s rendering of a BSO cellist. Harvard has never shown this trove donated by Ross.

Until recently, the Museum of Fine Arts has ignored Boston’s artists of Jewish heritage. The few examples on view represent slim pickings. I knew of Bloom’s “Christmas Tree,” 1939, but recently saw it for the first time. It was given by the museum’s Division of Education in 1952. The National Council of Jewish Women, in 1946, donated Levine’s “Street Scene No.1” from 1938.

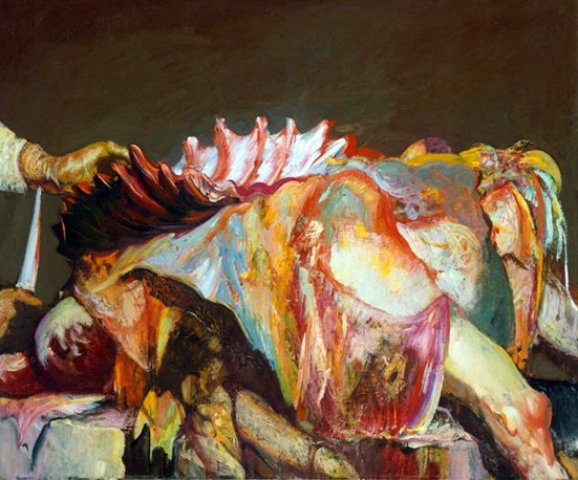

During the mid 1940s there was a period of critical interest in Boston’s artists. Bloom was admired by de Kooning and Pollock stated that he was the ‘first abstract expressionist.’ Initially, critic Clement Greenberg praised Bloom but was turned off when he failed to convert to abstraction. Bloom painted cadavers, rabbis and experimented with LSD. Levine bounced from “Sinatra in Vegas” to Judaica. As he told me “It felt more honest.”

Writing on Bloom the NY Times critic, Hilton Kramer, stated that approaching the gallery “I could smell the pastrami.” At Skowhegan in Maine, I confronted Kramer and he stated “It was just one Jew criticizing another Jew.”

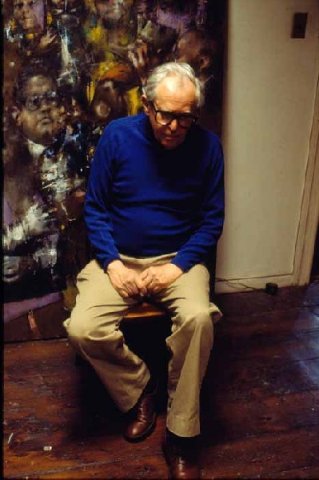

Initially major critics, art historians and curators were champions of their work. With changing tides Levine was lumped with the out of fashion Social Realists. Interest in Bloom faded and he became reclusive while exploring mystical philosophies and Eastern cultures.

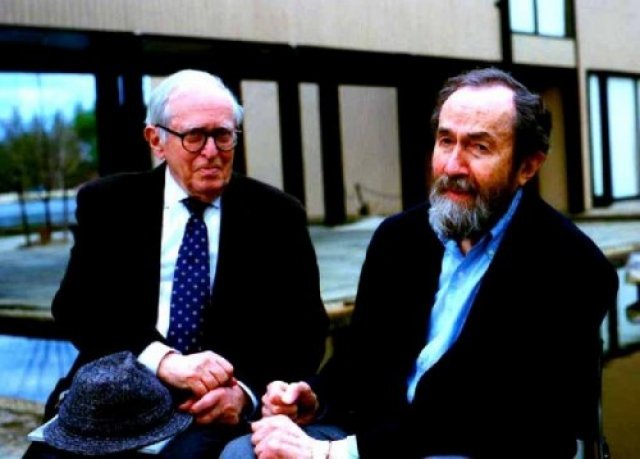

As Jack told me he didn’t like critics. But we got along just fine and I published a feature on him for Art New England. He wanted to commission Jimmy Breslin to write about him. Through his wife Stella I approached Bloom about an interview. The ground rules were off putting. One might visit but not view work in the studio. He rarely considered a painting finished. Tape recording or taking notes was forbidden.

The independent curator, Dorothy Thompson, met his terms. After visits she would rush home and write notes. Through this unique arrangement she organized the Fuller Museum of Art retrospective in 1996.

In 2010, the documentary “Hyman Bloom: The Beauty of All Things” was released. The film was written and directed by Angélica Brisk.

The former Boston Globe art critic, Sebastian Smee, on November 3, 2010 wrote that “Revelations about a reticent artist—Hyman Bloom, the artist, was not a recluse. He had a wide circle of devoted friends and acquaintances, and no end of younger artists who revered him. But he hated to talk about his work.

“He never showed up to openings of his own shows. And, as we learn in Angelica Allende Brisk’s superb, one-hour documentary, ‘Hyman Bloom: The Beauty of All Things,’ when Bloom would invite people back to his studio, all the works would be turned to the wall.

“Yet Bloom — mischievous, twinkly-eyed, habitually ironic — is the presiding spirit behind Brisk’s 2009 film, which uses footage from long interviews she did with the late artist (who was by then in his 90s and audibly short of breath). The footage brings Bloom incredibly close, humanizing the black-and-white still photographs of his early life and of the Jewish Ghetto in Boston’s West End, where he came as a boy from war-torn Latvia in the 1920s…”

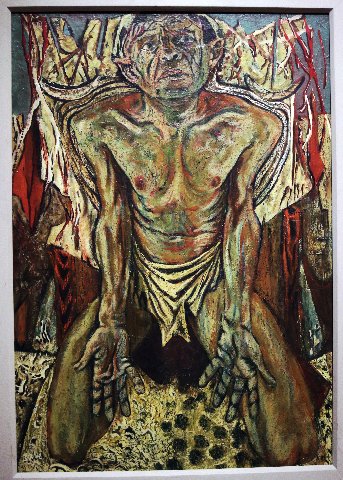

In the 1990s, William H. and Saundra Lane donated many American modernist paintings and photographs. This included a major cadaver painting by Bloom as well as the Zerbe encaustic painting “Job,” 1949, and “Disorder,” 1946.

From Copley, through Sargent and the impressionists, the MFA collected and celebrated Boston artists until the best ones were primarily Jewish.

The early Museum of Modern Art focused on School of Paris. A spinoff, the Boston Museum of Modern Art, after a famous split, became The Institute of Contemporary Art. Its founder, James Plaut, like Harvard’s Busch Reisinger Museum, concentrated on Germanic art.

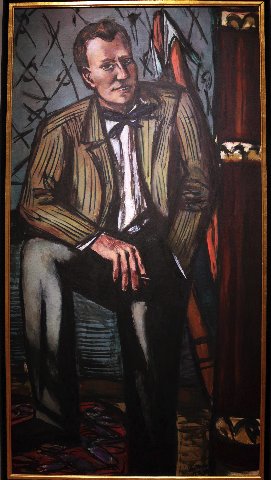

The young MFA director, Perry T. Rathbone, came to Boston from St. Louis where he had helped to sponsor the emigration of Beckmann. There is a full length portrait of him in the gallery. The ill treatment of Rathbone is documented in his daughter Belinda’s 2014 book “The Boston Raphael.” Senior curator, Hanns Swarzenski, was identified as ‘the bag man’ in a scandal which saw a spurious “Raphael” repatriated to Italy.

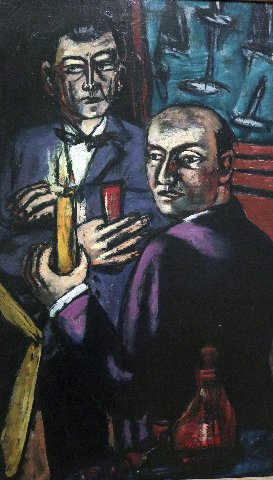

While shown the door by George Seybolt and the MFA board, Rathbone generously gave the museum his Beckmann. Similarly, Swarzenski donated “Double Portrait” which depicts him and art dealer Curt Valentin.

It is difficult to calculate the collateral damage when cultural institutions fail to support major artists in their communities. If the MFA cast a blind eye on Boston Expressionists there was no incentive for its trustees to collect.

Asiatics curator, Ananda Coomaraswamy, buried a gift of Stieglitz nudes of Georgia O’Keefe in the basement. Decades later they were “found” in an old bureau. For his MFA the good artists were dead ones.

Until recruited by curator, Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., the eccentric Lane had no connection to the MFA. Lane acquired only what fit in his station wagon. These works he shuffled around to regional schools, libraries and small museums promoting the cause of American modernism. Today, The Lane Collection which is rich in O’Keeffe, Dove, Demuth, Hartley, Davis, Sheeler and photography is viewed as priceless.

I was present when former contemporary art curator, Sheryl Brutvan, a Malcolm Rogers hire, visited Gallery Naga. She didn’t even glance at the work of then elderly African American artist, and Museum School graduate, Alan Rohan Crite.

Just as with Lane, in 2011, the museum acquired the John Axelrod collection which includes works by every major African American artist from the past 150 years.

These gifts from key private collectors help to fill gaps that were arrogantly and willfully ignored by the museum and its generation of Brahmin trustees. While there was enough work to fill a single gallery it remains a scandal that the museum, for example, does not have a major work by Levine. Bloom and Zerbe are represented with major works but no depth.

The market for these artists remains undervalued. Major works command less than $100,000. The oeuvre of Bloom includes some 300 paintings and thousands of sketches and finished works on paper.

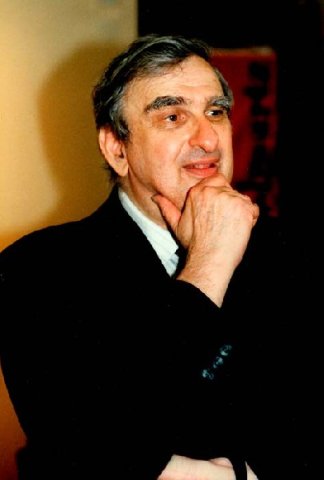

During a visit there was a chance encounter with MFA director Matthew Teitelbaum. Years ago, I knew him as a brilliant ICA curator. I recalled his remarkable show “Montage.” Discussing the German and Boston Expressionist gallery he shared my enthusiasm.

I was surprised when he stated that “Erica Hirshler is curating a Hyman Bloom show for us. It will be a couple of years from now.”

Some years ago a Bloom show was proposed by former curator Stebbins. It is said that the artist and his wife Stella were invited to the museum and shown where it would be installed. Hirshler was his assistant at the time. Without explanation that project ended abruptly.

There have been prior shows of the Boston Expressionists. With its considerable resources, however, it is anticipated that the MFA will right an egregious wrong with a definitive Bloom exhibition and scholarly catalogue. This is likely to stimulate collectors and scholars with related projects. When, for example will the Harvard Art Museums finally show the Denman Ross collection of Bloom and Levine drawings?

If the MFA is finally doing the right thing for Bloom is that scholarly effort backed by major acquisitions? Now that the museum is looking at Bloom will it widen its focus to exhibit and collect Boston’s unique generations of figurative expressionism? For starters, no Boston or regional museum has organized shows of Levine and Zerbe. There is much work yet to be done.

A version of this article previously was posted by Boston's The Arts Fuse.