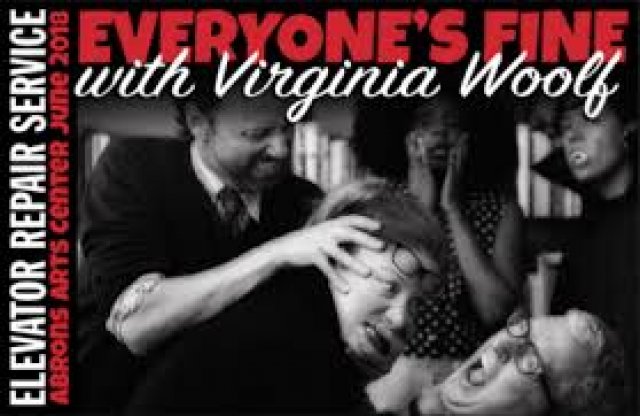

Everyone's Fine with Viriginia Woolf

Kate Scelsa Re-constructs Martha at Elevator Repair Service

By: Rachel de Aragon - Jun 30, 2018

Elevator Repair Service presented Kate Scelsa's Everyone's Fine with Virginia Woolf. This production at the Abrons Art Center is a re-construction of Martha in Edward Albee's play. Director and company founder John Collins takes us seamlessly back into the world of Albee, Tennessee Williams and Samuel Beckett to deliver an hilarious and scathing 21st century production.

Back in that so familiar living room with Martha and George, Albee's take on sex and marital conflict is pushed to new extremes. In Albee's version, Martha's fight for her own reality is defeated by the fact that she is a woman. Playwright Scelsa declares she has come to avenge Martha.

The new setting is thoughtfully re-imagined by Louisa Thompson. Albee's themes of false pregnancy and life conceived and destroyed within the construct of artistic reality continues with a different twist.

The play skewers the whole notion of femaleness as a stand-in for the essential emotional, anti-intellectual motivator. Skillfully referencing the plays of 20th century icons, Williams and Beckett, Scelsa restructures their social assumptions.

The play skewers the whole notion of femaleness as a stand-in for the essential emotional, anti-intellectual motivator. Skillfully referencing the plays of 20th century icons, Williams and Beckett, Scelsa restructures their social assumptions.

The dialog is vibrant and brimming with humor. The actors do it justice. Annie McNamara brings intensity to her Martha and supports the sharp duel with veteran ERS actor Vin Knight as George. The innocent guests, Nick and Honey remain questionably culpable. April Matthis and Mike Ivesson bring a touch of humor to their roles.

Albee often takes on subjects outside our comfort zone. He looks at our capacity for sadism and violence. Sexual attraction wears many suits. Death always hangs over us.

Scelsa begins where Albee ends. Her barbs are tipped with flavors from theater of the absurd. Her use of language reduces pomposity to its most laughable core. The perfect suburban home, the 'bubble' in which we have been asked by Albee to believe exists, collapses.

There are dirty clothes on the floor-- which must be hurriedly thrown in the other room as guests arrive. There are no hooks to hang the coats, dexterously removed from shoulders. There is 'no exit' through a mysterious garage.

Alcohol flows freely, but, like the other props of conventionality, it ceases to be the explanation. Men are in the living room with liquor; women in the kitchen with chicken. The set comfortably accommodates both spaces.

The collapse of the setting ultimately becomes physical with the death of George. His space is hell itself, ferried via GPS by a current female PhD student.

The collapse of the setting ultimately becomes physical with the death of George. His space is hell itself, ferried via GPS by a current female PhD student.

Scelsa puts the sexuality's dangerous irrationality right on the table. All of the characters are gay, or may be. George is a professor of English whose thesis on Tennessee Williams supports the view that female characters are expressions of the playwright's femininity. He himself comes to inhabit more than one of Williams' women. We are not sympathetic as the misogyny takes on a life of its own. Martha is a housewife who housekeeping skills are notably minimal. Bi-sexuality, as well as murderous rage, make Martha the appointed avenger of her own dilemmas.

We are, like the guests at George and Martha's, required to be uncomfortable. We do not have to like our hosts to be enormously entertained.

We are, like the guests at George and Martha's, required to be uncomfortable. We do not have to like our hosts to be enormously entertained.