Die Walküre

A Tale of Conflicts and Betrayals

By: Victor Cordell - Jul 28, 2025

No accomplishment in the world of opera exceeds Richard Wagner’s four opera Der Ring des Nibelungen or Ring Cycle compendium. With 15 hours of staging and 28 years in the making, it was a massive undertaking. Apart from extensive storytelling and the quantity of music involved, its intellectual integrity distinguishes it with its focus on a detailed dramatic arc; continuous music at the expense of popular set pieces, with no ensembles and choruses; and elaborate use of leitmotifs to identify characters and moods. Nonetheless, purity does not ensure that all will find the outcome entertaining.

While the four operas constitute a whole that is intended to be seen together over a short period of time, Die Walküre is the one that perhaps stands alone most successfully as a complete story with a satisfying beginning and end – even if complete closure is not reached. Among the many moral issues from incest to integrity, it deals with one great moral dilemma, betrayal, expressly and in considerable depth that gives it an extra dimension. Santa Fe Opera offers the opera for its very first time, and the result is magnificent.

At 4 ½ hours run time including two intermissions, Die Walküre’s storyline reduces to a few basic transactions. The opera opens with Siegmund, portrayed by tenor Jamez McCorkle, displaying a huge voice, especially in a sequence calling for his deceased father. He takes refuge in the home of what turns out to be an enemy, Hunding (Soloman Howard, with a rumbling bass voice), whom he must fight to the death. Siegmund falls in love with the host’s wife Sieglinde (soprano Vida Miknevi?i?t?). They find they are siblings, but their tryst leads to pregnancy that will ultimately produce Siegfried, the hero of the next opera in the cycle.

Wotan (bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Green) is the king of the gods, and mortal Siegmund has descended from his illegitimate child. However, Wotan’s wife Fricka (imperious mezzo Sarah Saturnino), is an ally of Hunding’s family and resentful of Wotan’s promiscuity that ultimately led to Siegmund’s birth. She insists that Wotan use his power to ensure Siegmund’s death in the battle.

Meanwhile, Brünhilda (soprano Tamara Wilson), the leader of the Valkeries, who are the daughters of Wotan, sympathetically aids the illicit couple, as Sieglinde had been abducted and abused by Hunding. Although her assistance fails, Wotan disowns his favorite daughter and alter-ego for her betrayal and reduces her to a mortal to lie in a sleep state until discovered by a man and taken for his wife.

That process is perhaps the best developed moral internal conflict in the Ring Cycle, one that reflects dilemmas that leaders of all kinds face when a beloved or highly valued underling has betrayed trust. The punishment pains the leader as well as the follower. Wagner was nothing if not thorough in his narratives, and this is a good example of why Ring operas are so long, as he dwells on this issue for much longer than needed with the verbal clashes and bouts of empathy between Wotan and Brünhilde.

Led by the commanding voices of Green and Wilson, cast selection is impeccable, and they deliver the goods. Wagnerian singers must possess powerful voices with heroic, some would say harsh, tone able to compete with the large orchestra that Wagner demands. To make sure that the singers get an adequate workout, roles with higher vocal ranges generally have high tessituras as well. And though Wagner eschews the notion of arias, each principal has at least one long, highly challenging soliloquy.

The biggest surprise of the evening was Miknevi?i?t? as Sieglinde. Despite a distinguished European career, this was her American debut, and she wowed with the easy power and range of her mellifluous voice and her compelling stage presence.

The more melodic music in the Ring is often in the orchestra, and perhaps its most famous is the stirring “Ride of the Valkeries,” whose motif recurs through the final two acts. Associated with it is Brünhilde’s equally spirited “Hai Jo To Ho” which Wilson delivers with relish. Otherwise, it is notable to remember that while singers exert and then relax or disappear during the opera, the orchestra performs the whole time, and musicians’ lips and fingers can tire. Kudos to Conductor James Gaffigan and the orchestra for not only enduring, but excelling.

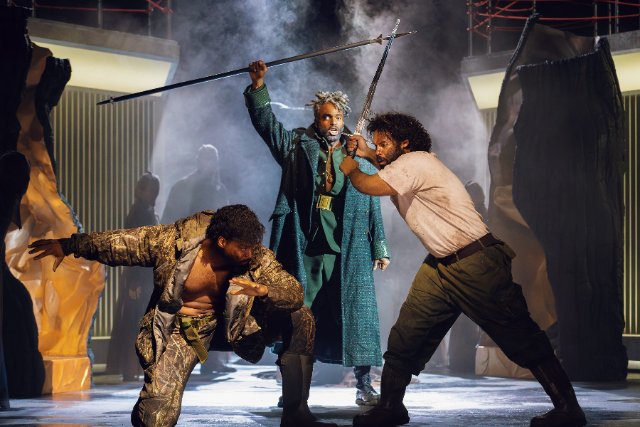

Director Melly Still and Scenic Designer Leslie Travers’s stunningly sharp abstract look in Acts 2 and 3 is simple in its appearance but complex in its design, which is easier to understand by seeing the included images than reading about it. Stands of closely-arranged vertical, white rubber ropes span the full breadth of the stage. Irregularly arranged red ropes decorate above the white rope frame. The white ropes convey separation and opaqueness, and their flexibility allows the functionality of egress for the characters. The red ropes presumably represent entanglement. Truncated trees and other scenic references to reality occur to enhance the meaning and the visual presence. Add to it Travers’s striking costumery for supernumeraries plus their depictions and movement as horses, dancers, and others, and the visual array is superb.

The part of the visual design that detracts from the overall effect is Hunding’s modern dilapidated house with rusted appliances in Act 1. Likewise, the costumes and makeup of the principals are shabby and make the players look like homeless people, and that even extends to Wotan when he goes topless.

Hunding’s wealthy family are close associates of the most powerful goddess, Fricka, and the others are descendants of the leader of the gods. Not only does this look seem inappropriate for the station of the characters, but it is aesthetically unpleasing. There are many ways to be creative in design, but unlike the thoughtful scenery in Acts 2 and 3 as well as the interesting depictions of non-principal players, this portrayal of poverty or slovenliness serves no appealing purpose.

In any event, the production marks an exemplary debut by Santa Fe Opera of this notable work.

Die Walküre with music and libretto by Richard Wagner is produced by Santa Fe Opera (www.santafeopera.org) and plays on its stage at 301 Opera Dr., Santa Fe, NM through August 21, 2025.