A Room of Her Own: British Women at Clark Art Institute

Epic Struggle of Emerging Artists Between the Wars

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 03, 2025

A Room of Her Own: Women Artists in Britain, 1875–1945

Organized by the Clark Art Institute and curated by Alexis Goodin, associate curator.

June 14 through September 14, 2025

Celebrating twenty-five women artists working in Britain between 1875 and 1945, the Clark Art Institute presents A Room of Her Own: Women Artists in Britain, 1875–1945 featuring 87 paintings, drawings, prints, stained glass, embroidery, and other decorative arts. The exhibition explores the spaces these women claimed as their own and which they used to further their artistic ambitions, including their rooms, homes, studios, art schools, clubs, and public exhibition venues. Their roles in creating change and opportunity—whether through art education, marching for women’s suffrage, protesting World War I, or establishing spaces and organizations for fellow artists or members of their community to come together—is highlighted in the exhibition.

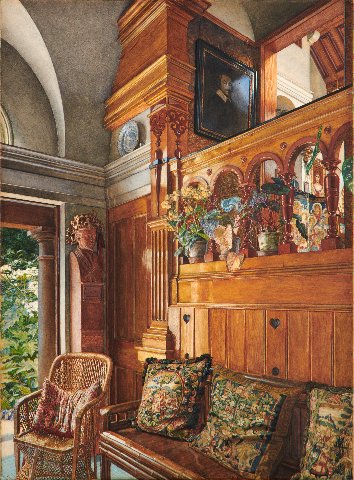

In 2020 the Clark acquired, The Garden Studio, by Anna Alma Tadema (1867-1943). The 1886–87 work in watercolor has traces of gum Arabic, and scratching out on paper stretched over a wooden frame. It is a small but intense, super realist rendering. Based on this acquisition Clark curators wanted to know more of her work as well as that of other generally obscure and forgotten women artists.

Although one of the most successful artists of the Victorian era her father, Sir Lawrence Alma Tadema, (1836-1912) was later largely forgotten although interest and market value returned later in the century. Dutch/ Belgian by birth and training his meticulous approach to rendering is consistent with the Ruskinian dictum of “Truth to Nature.”

In 1978 the Clark acquired his 1887 painting “The Women of Amphissa.” The Clark’s website describes it as “Followers of Bacchus, the god of wine, awaken in the marketplace of Amphissa, Greece, where they have wandered from their home in Phocis during a night of ritual dancing. Amphissa and Phocis are at war, but the women of Amphissa graciously offer the bacchantes nourishment and protection. The painting illustrates an event recorded by the Greek historian Plutarch, which Alma-Tadema staged as a lesson in charity for his Victorian audience.”

Technical aspects of his technique are evident in three works by his daughter on view in this exhibition. There is also a small self portrait in oil as well as “Girl in a Bonnet With Her Head on a Blue Pillow (Maisie),” 1902, a watercolor. In this study of her friend, Anna, who never married, expresses tender affection and sentiment. Like many of the artists in this exhibition she was dedicated to the cause of women’s suffrage.

This survey gets its title and theme from a famous 1929 essay by Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) “A Room of Her Own.” It was thrilling to see a first edition with a cover designed by her sister Vanessa Bell. Other books with covers by Bell, who is well represented in this exhibition, are on display. There is also a still life as well as an ersatz modernist self portrait.

Most of the work in the exhibition is conservative, tentative and at times dark and dreary. There is an emphasis on sentiment, vividly illustrative imagination, with a focus on the unique vision and sensibility of women. Many of whom were suffragists who pushed the glass ceiling. One might just imagine the difference were this a survey of French women of the same period.

Not to say that male British artists were any more progressive. A number of works in this exhibition reflect the Arts and Craft movement or the outré Pre Raphaelites. They have their defenders but seem like weak tea compared to the avant-garde, modernist cultural revolution of French art and culture. An argument may be made that the British were more adventurous and insightful writers than visual artists.

In “A Room of Her Own,” Woolf argued that to write fiction women need their own physical space in which to think and create, as well as a sufficient income to support themselves. Overcoming many obstacles the women in this exhibition did exactly that. Most worked in their homes but eventually had studios. Gradually they studied at art schools where life drawing was restricted. They pried their way into exhibitions including showing in their homes and studios. Some became established professionally. During the two World Wars they devoted their efforts to supporting the nation and replacing jobs of men in uniform.

In her essay Three Guineas (1938), Woolf recounted the limitations imposed upon young women by society. “It was with a view to marriage that her mind was taught; . . . that she . . . sketched innocent domestic scenes, but was not allowed to study from the nude; read this book, but was not allowed to read that. . . . It was with a view to marriage that her body was educated; a maid was provided for her; that the streets were shut to her; that the fields were shut to her; that solitude was denied her.”

Louise Jopling (1843–1933) and Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919) earned more than their spouses at various points in their careers and financially supported their families, while Helen Allingham (1848–1926) increased her watercolor production after her husband’s death to provide for herself and three young children.

At a time when lesbian partnerships were not openly discussed—and male homosexuality was criminalized—some women artists formed lifelong domestic partnerships with women. Nan Hudson (American, active in Britain, 1869–1957) and Ethel Sands (British, born United States, 1873–1962) did not hide their romantic relationship. Mary Lowndes (1856–1929) lived and worked with Barbara Forbes for much of their lives, and the two women played active roles in the Artists Suffrage League which was founded by Lowndes. After several difficult relationships with men, May Morris (1862–1938) found companionship with Mary Loeb. Gluck (née Hannah Gluckstein 1895–1978), rejected gender norms in both appearance and relationships. In moving beyond expected gender roles, women artists featured here became activists for new ways of living and loving.

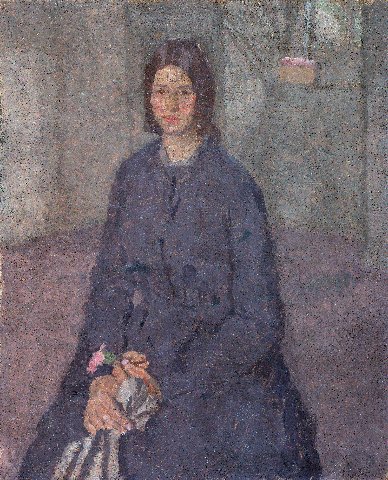

Entering the galleries one of the first works we encounter is the somber “Portrait of a Woman,” 1917, by Nina Hamnett. The painting is dark and may need cleaning. It depicts a woman, reading at a desk with an arm supporting her head. There are books on shelves behind her.

There are studies for textiles as well as work by William Morris (designer) and May Morris embroidery. A singular work is “Tudor Rose” designed by May Morris with needle work, silk on linen, by Dame Alice Mary Godwin.

May was the daughter of the Pre Raphaelite artist and designer William Morris (1834-1896). He was a founder of the British Arts and Crafts Movement. May learned to embroider from her mother and her aunt Bessie Burden, who had been taught by William Morris. In 1878, she enrolled at the National Art Training School, precursor of the Royal College of Art. In 1885, aged 23, she became the Director of the Embroidery Department at her father's enterprise Morris & Company. During her time in the role she was responsible for producing a range of designs, which were frequently misattributed to her father. She ran this department until her father's death in 1896, where she moved into an advisory role.

A thrilling highlight of the exhibition features ten plates from the “Famous Women Dinner Service.” Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant were commissioned to create 48 plates for art historian Sir Kenneth Clark and his wife Lady Jane Clark. The series of hand painted, Wedgewood plates were created in 1932-34. Was Judy Chicago aware of them when she created “The Dinner Party” (1974-79) which similarly celebrated famous women?

The paintings of Gwen John, such as “The Brown Tea Pot,” 1915-16, feature closely valued gradations. Are they poetic and understated or simply dull? I went on line and found more interesting works. It was a surprise to learn that the Welsh born artist resided primarily in France and was a lover of the sculptor Auguste Rodin. This is an artist who might have been presented in greater depth.

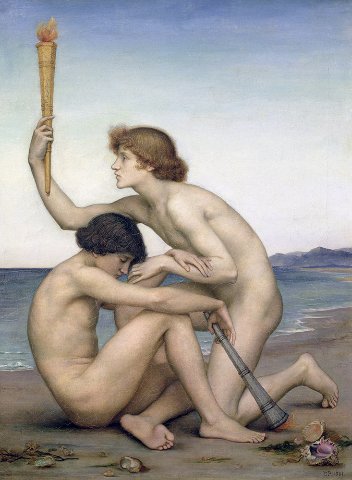

“The Red Cross,”1914-1916, by Evelyn de Morgan expresses her pacifist views. The over the top imagery tugs at our heart strings. With outstretched arms Christ in red hovers over a field of crosses marking the graves of soldiers. A host of angels, their risen souls, cling to him. She exhibited it along with ten other works in a rented Chelsea studio. Entry was free but she asked visitors to donate to the Red Cross. In another work she depicts mythology with the figures of “Phosphorus and Hesperus.” They represent the morning and evening stars.

A bright spot entails encountering a large stained glass work “The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple,” 1910, designed by William Holman Hunt and fabricated by Mary Lowndes. It was created in The Glass House, which she helped to found, a glass studio open to independent artists.

Louise Jopling (1843-1933) was a successful artist. She and her second husband, also an artist, built two studios. That allowed her to separate her private and professional life. She is seen here with a self portrait, 1875, “Through the Looking Glass” and two women in white washing pottery. A puzzle is why such elegantly attired women are washing pottery? This is work for maids and not women of their social status. The artist has set aside social reality in order to create a lush and realistic rendering of soft flowing fabric and colorful blue and white pottery.

Winifred Knights, The Deluge, 1920, oil on canvas, has the stylized abstraction of the Art Deco movement. The work is engaging for its distinct difference from the rest of the work in the exhibition. Its large flat areas give the work a strongly graphic sensibility.

This apocalyptic painting was produced as a competition entry for the final of the 1920 Prix de Rome scholarship in Decorative Painting. From an initial selection of seventeen artists, Knights was chosen to go forward to the final round. The theme of The Deluge was designated with eight weeks allowed for the submission of a painting in oil or tempera and a cartoon. The size of the painting, 5 by 6’, was also set in advance by the judges. Knights began working on the canvas in July 1920. Despite suffering from tonsillitis and eye problems over the summer, and submitting her painting partly unfinished, she won the award, taking up the three-year scholarship at the British School at Rome in November.

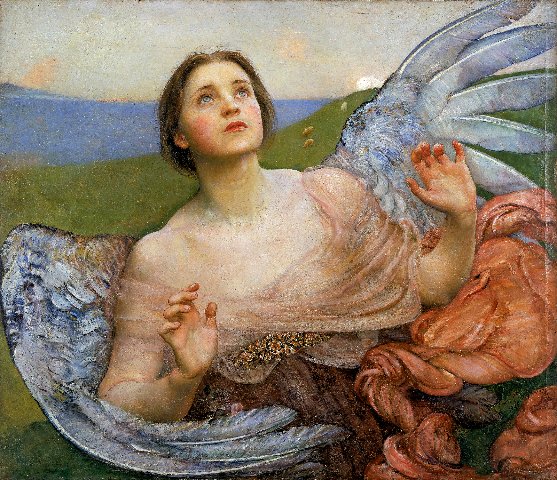

An excess of narrative sentiment is off putting in “The Sense of Sight,” 1895, by Annie Louisa Swynnerton. Again we encounter an obsession with angels. Her skill as a figurative painter is conveyed in a rare female nude, “Mater Triumphalis.” In 1879 she co founded Manchester Society of Women Artists which provided opportunities to depict nude models.

In 1922 Swynnerton became the first woman elected as an Associate of the Royal Academy since its opening. Ironically, Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807) and Mary Moser (1744-1819?) co-founded the organization in 1768 which was later closed to women artists. In a newspaper interview over a decade later, Swynnerton reflected: “I have had to struggle so hard. You see when I was young, women could not paint, or so it was said. The world believed that and did not want the work of women however sincere, however good. I refused to accept that.” Today, women hold thirty-eight of the 100 membership positions of the Royal Academy.

Gluck, 1895-1978, was the professional name of a lesbian artist. She is represented here by a pedestrian study of tulips, acquired by Queen Mary, and the juxtaposed profiles of the artist and her partner.

She was born Hannah Gluckstein. Her family owned the Lyons catering empire in London. Her parents weren’t in favor of an artistic career, but nevertheless, they trusted her with a fund that allowed the young artist to make a life of their own.

Gluck attended St John’s Wood School of Art between 1913 and 1916 before moving to West Cornwall and joining the artists’ group in Lamorna and purchasing a studio. However, she didn’t want to be a part of any movement and always insisted on solo exhibitions.

The cycle of the exhibition ends with the evocative wartime works of the remarkable Dame Laura Knight. In a vividly painterly manner, “Balloon Site, Coventry,” 1943, depicts members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force raising unwieldy balloons as defense of industrial cities. The vigor of her work is exhilarating.

Women artists were commissioned to record scenes of war activities on the home front. Anna Airy completed five large paintings showing munitions work in Great Britain in 1918 for the newly formed Imperial War Museum, including “Shop for Machining 15-inch Shells, Clydebank” and “An Aircraft Assembly Shop, Hendon”. Lucy Kemp-Welch memorialized the work of the Women’s Land Army Agricultural Section in “The Ladies’ Army Remount Depôt, Russley Park, 1918.” The War Artists’ Advisory Committee acquired seventeen canvases by Dame Laura Knight showing war efforts in Great Britain.

This pioneering, scholarly exhibition at the Clark retrieves these women artists from the dust bin of time and neglect. In some instances it makes us eager to know more.