Dishwasher Dialogues: Switzerland

Christmas in Paris

By: Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Aug 03, 2025

From The Dishwasher Dialogues

Dreaming of Switzerland

RAFAEL: Chez Haynes was closed for Christmas Eve, but not for December 25th. That was a long night too. How did I spend Christmas Eve? I never remembered those religious holidays. For me, they weren’t memorable. I had no children, and the 25th in those years was just another day in Paris. When I was a boy in boarding school, that’s where I spent the holidays, with a few others who couldn’t go home for the holidays; my friends and I rattled around that massive building in the center of Vienna. Later in Paris, I was free, and I had a job and dreams of exhibiting my paintings. That evening, we gave each other small presents when we went to Chez Haynes, but to my shame, I can’t remember what they were. We probably gave each other books, we all loved books.

GREG: Dusty, first edition, self-published books by poets who went before; from Shakespeare and Co. bookstore. That’s what I gave. I also remember many gifts exchanged that came in the form of a bottle.

RAFAEL: December 31st was also a big night, and at midnight I kissed and hugged the waitresses, the men shook hands or slapped each other on the back, something like that.

GREG: Not a kiss, except with one of our Parisian regulars. But surely a hug? Even the dishwasher deserved a hug. I had taken my wet apron off.

RAFAEL: A few clients kissed the waitresses.

GREG: And a few waitresses even kissed the dishwasher.

RAFAEL: We were all friends and unattached, and that seems unusual in retrospect.

GREG: Unusual? How?

RAFAEL: I mean by this that we were creative, and dreamers, with hope and vision, and that made for an unusual bond between us. We respected each other but we also felt our quest, whatever it might be, was a solitary one.

GREG: I think I understand what you are saying. But dreaming does not have to be done alone.

RAFAEL: What would the new year bring? There was a palpable sense of hope among us young people, and a brittle happiness in our laughter. We sang Auld Lang Syne, and I thought of my childhood in Spain and how we ate one grape at every gong of the church bells. Some clients cried. What were we to do to celebrate the New Year after closing time? You suggested we drive to Geneva. We would all pile into my VW beetle and head for the Swiss border.

GREG: There was time to do so. I think we had three days off.

RAFAEL: To this day, I never understood why you were so glommed on to that Geneva idea. What would we do in Geneva for a whole day or half a day? Where would we stay? And we had no money, even for the gas, let alone for a student hostel or a meal.

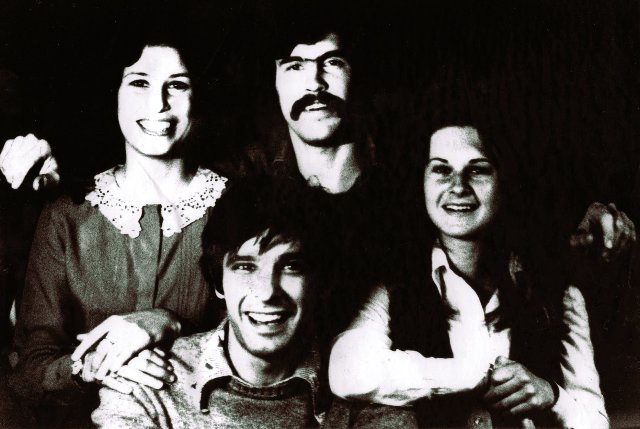

GREG: I will concede I was very keen about just taking off for a few days and Switzerland was as eccentric a destination as the idea of just taking off for the hell of it was. And I was not the only one. Laura and Sophia—we were all very good friends by then—were also very enthusiastic. We spent many hours one evening trying to persuade you. It was going to be our New Year’s holiday. ‘Let’s just go. Right now,’ I said. ‘What have we got to lose? It will be an adventure.’ At times you almost caved, but there was always something pulling you back from the threshold. It was not because the whole idea was ludicrous or just plain absurd. When did that ever stop us? It did not normally stop you. If anything, that was a major part of the excitement. Let’s just see what happens in the mountains. Or on the way. And it wasn’t the gas. Small car, four of us, pooling our money. It was a holiday after all. We could splurge a little. At some point, you claimed it would be “boring” which never meant “boring” but hid something else. Maybe it was your youth spent in Austria all those years ago. The mountains may not have held much mystery, or significance or excitement. Possibly the reverse. I don’t know. We never talked about it that much.

RAFAEL: Ever since my boarding school days in Vienna and going on school skiing trips, mountains mean snow and snow means cold. I was cold those four years in Vienna. To this day give me the Mediterranean heat. Maybe I have some kind of vitamin deficiency, but I get cold easily and I hate it. So, the Alps, my friend, were not an attraction for me.

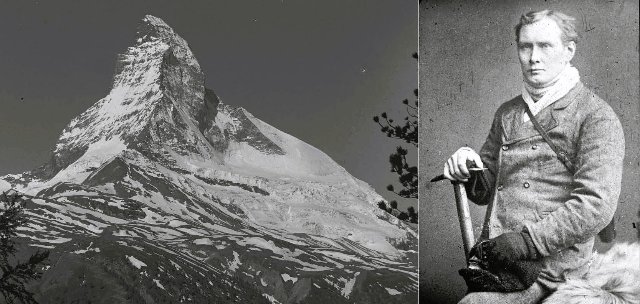

GREG: Whereas, the mountains, I confess, held a magical sway over me. They always have, since I read a book about Edward Whymper’s tragic climb of the Matterhorn when I was about 10 or 11 years old. A few years before our “almost” trip, I visited Switzerland as part of a gap-year-hitch-hiking journey around Europe. Near the end, I went to Switzerland and took a cable car up the side of a mountain across the valley from Mont Blanc. I found two weeks’ work, scraping old paint from alpine windows at a closed-for-the-season ski lodge. The work was tedious, but the air and the view were fantastic. Even noumenal. That is as close as I have ever got to Nietzsche’s Eternal Recurrence moment. Well, then and forty years later in a blizzard near the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro. (I told you I liked mountains.) Maybe that same longing was swirling in my mind on that New Year’s Eve evening in Paris. As the evening and conversation wore on and our Swiss adventure slid into ancient possibility, we eventually fell back on the old-time holiday favorite, wine and good cheer, the latter holding sway for as long as the former lasted.

RAFAEL: Geneva became, for me, a symbol of what was beyond reach. Silly, I know, but I think we all have our own signs for what we missed.

GREG: You were thoroughly entrenched in Paris. That is for sure. You rarely left the city, even when you could, unless for a show, an exhibition, a production. And to see family. The world outside was not so much beyond your reach as, possibly, not worth reaching. Except for love and art.

RAFAEL: That night, about two hours into the new year, I drove around Paris, dropping some of the staff off at their homes.

GREG: Yes, you would leave your arrondissement. Given we lived all over Paris, it was a considerate gesture. You were generous that way. Although, in retrospect, you could hardly abandon us to the streets long after the metro had ended for the night. Not on the first day of the year.

RAFAEL: I lived near what would later become the Centre Pompidou, but at the time there was only a big hole in the ground. On Boulevard Sebastopol some diehards were still honking their New Year horns. I parked the car, entered my building. I checked the mailbox. Nothing. I climbed the stairs to my third-floor apartment. I flopped down on my mattress and stared at the ceiling until I fell asleep.

GREG: I like to think I dreamt about the Matterhorn that night.

RAFAEL: The next day I woke up late and after a coffee and a croissant, I strolled down to the Seine and looked at what the bouqinistes had for sale. I bought a dogeared book by André Breton called Nadja. A strange book with photographs of a love affair. I never entirely understood it.

GREG: And to think you could have been reading in Switzerland, lazily perusing Nietzsche’s The Joyful Wisdom.