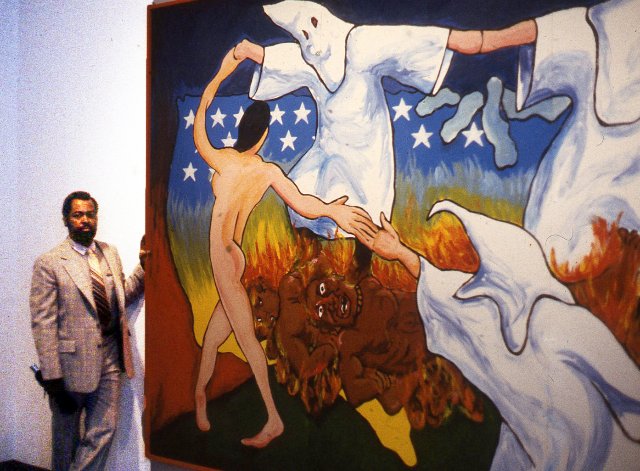

Dana C. Chandler, Jr. Artist and Activist at 84

Protested MFA and Founded AAMARP at Northeastern University.

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 09, 2025

During the protest years of the late 1960s and 1970s the artist and activist, Dana C. Chandler, Jr., charged the Museum of Fine Arts with institutional racism. The proclamation was sent to the Boston print and broadcast media.

This initiated meetings with MFA administrators and talks that resulted in an exhibition "African American Artists from New York and Boston." Hired to curate the exhibition Edmund "Barry" Gaither was appointed an adjunct curator of the MFA while serving as director of the National Center for African American Artists in Roxbury (founded in 1968). The museum had started as a part of the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts (founded in 1950) which suffered a series of fires leading to the destruction of the facility through arson.

In 1974 Chandler founded African American Master Artists- in- Residence Program (AAMARP) at Northeastern University.

“Dana C. Chandler Jr.’s impact on the arts community in Boston is immeasurable,” ICA curator Jeffrey De Blois told the Bay State Banner. “His art was brash and direct, frequently taking the multifarious, interlocking forms of American racism as its subject. Beyond his influential artwork, he was a tireless advocate for Boston’s Black artists, especially through the African American Master Artists-in-Residence Program he founded at Northeastern University. Chandler was a pillar in the community, someone who believed irrevocably in the transformative power of art and museums, a champion of access and someone who held the city’s arts institutions accountable.”

Chandler retired from teaching at Simmons College and in 2004 relocated to Gallup, New Mexico. At the time he told me that he was protecting his son from gangs.

In response to what I posted he stated,

"https://www.isr.umich.edu/home/diversity/resources/white-privilege.pdf Charles you need to read this before we continue.. you're writing this from a white privileged point of view, as if your memory of those times in our black history is the more accurate historical view; as though your role as observer rather than a participant is a truer picture. Please don't ’Brian Williams’ me. This is not your story..."

The following interview occurred in 2015.

Charles Giuliano My concern is contemporary art in Boston and your involvement during the activist years of the late 1960s into the 1970s. My first encounter with your work was a mural. It was one of a number commissioned by the Summerthing project sponsored by Mayor Kevin White. Drew Hyde (later director of the Institute of Contemporary Art) was working with Edmund Childs an architect. They were creating pop up playgrounds in abandoned lots in the South End. Murals were a part of the program. I was trying to recall the location and date of the one you created.

Dana C. Chandler, Jr. Mass and Columbus Avenue before the Harriet Tubman house was there. If you go into the ICA archives there are postcards of the murals.

(Checked and was unable to find this reference.)

CG In Boston After Dark I wrote about Gary Rickson's murals on the exterior of the YMCA in Roxbury.

DC I think it's now on the rear wall of the YMCA. I may be wrong it may be on the front of the building.

CG There was a mural by Roy Cato, Jr. I don't think it still exists. They came and went

There was controversy about your mural and I recall that you came to see me about it in my office at Boston After Dark. You were also a participant in the Studio Coalition the first open studios event. There was a group shot of the artists on a roof top that became the image for a poster.

DC It appeared as the cover of a small magazine as well.

CG The Gallery Guide. There was also coverage in Art News as I recall.

DC It was a long time ago.

CG Can you recall your state of mind at that time?

DC It's best spoken of when I delivered that proposal to eradicate institutional racism at the Museum of Fine Arts. I felt that we were excluded. Of course I still feel that way. It was December of 1969. The article in Boston After Dark came out in January 1970.

CG Was that under your byline?

DC The article? No. That was written by somebody else.

CG Was there an involvement with Barry Gaither at that time?

DC He was not at the MFA at that time. He was hired around the time of the exhibition.

CG You are talking about the centennial year exhibition "African American Artists from New York and Boston" which was initiated by the artist Barney Rubenstein of the Museum School. It then got taken over by Barry. Is that correct?

DC I think it was a more collaborative thing. I think Barney knew a lot of the African American artists in New York. But Barry was more intimately involved with them. They were more his friends than Barney's. I think.

CG Were you in that exhibition?

DC Yes I was. I was the initiator of the exhibition. The museum had no intention of having that show prior to my delivering that proposal to eradicate institutional racism. At the same time I delivered it to the MFA I delivered it to every newspaper, television and radio station in the area at that time.

CG How many ran it?

DC Boston After Dark was the first to do a large article and after that the Globe and Herald. There were some television shows on it Channels, 4, 5 and 7. That was probably more when the exhibition was up.

CG Was this an actual protest with demonstrations at the MFA or was it delivered as a text?

DC It was delivered as a text and then I think there was some picketing. Someone went in and did some damage to a Rembrandt painting. I think that's what initiated my meeting with the board of directors of the museum. (George) Seybolt and all those people at the time.

CG I have to correct your facts. It wasn't a Rembrandt. I believe that the damaged painting was "Daughters of Edward D. Boit" by John Singer Sargent.

DC Ok. But the museum was concerned that black folks would run through the galleries slashing paintings and all that.

CG Didn't your actions inspire those fears given the climate of the time?

DC My proposal was not. What inspired someone to do that I have no knowledge of. I had nothing to do with that.

CG It was a time of radical protest. It was the era of Malcolm X and the Black Panther Party. It was the climate of the times and perhaps you were a reflection of that.

DC I was seen as a reflection of that. Yes.

CG How did you feel?

DC Of the time of protest?

CG Of the radical branch thereof.

DC Oh yeah.

CG For example Malcolm's mantra of "By any means necessary."

DC (pause) I'm thinking. No. I never had any thought or intentions of running through the MFA with knives or any of that foolishness. I had too much respect for the art. But, non violent protest? Yes.

CG But that (radical and violent protest) was in fact the imagery in your work at the time.

DC Oh yeah. But I wasn't going to make Molotov cocktails. The feeling of young African Americans at the time is very similar to what they feel today about Ferguson. That if there aren't changes made it can escalate. We also were aware that a lot of changes in the government were going to be made by COINTELPRO the ones that destroyed the Black Panther Party.

(COINTELPRO (an acronym for COunter INTELligence PROgram) was a series of covert, and at times illegal, projects conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveying, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting domestic political organizations. National Security Agency operation Project MINARET targeted the personal communications of leading civil rights leaders, Americans who criticized the Vietnam War, including Senators (e.g., Frank Church and Howard Baker), journalists, and athletes.)

You can find a lot of that information on You Tube. It was a government organization put together by the FBI. There may have been other agencies. It was Hoover's intention to infiltrate radical organizations and destroy them. These are not my words.

CG Were you acting alone or were you a part of a group? Was there a committee?

DC No, I was pretty much acting alone. I got supported by any number of groups once that came out. The support was more verbal than actionable. The Perry Rathbones (MFA director) and people like that would call leaders in the black community and ask "Are we at fault here? Have we not done enough? Or have we done anything?" The activity of the MFA in the black community was nil. Until the Elma Lewis center came about. When they inquired of her asking "What the hell is going on? There's some crazy black folks." She responded "No these are people in our community who have noted that you have not given us our fair presence in the museum. How can you be across the street from the black community and not have any black artists on your walls?"

CG Was the MFA responding to threats?

DC The answer to that is yes. If it had not been for my proposal and hearing from people in the black community upon hearing of the Sargent (slashing) they said that they were not surprised. There's no indication as to who did it. And it certainly wasn't me. I wouldn't do such a thing. I like John's work.

CG I didn't realize that you were on a first name relationship with him. I didn't know that. You may have applied leverage at the right time. But there were other factors. It was the centennial year and exhibitions which had been planned fell through. So at the last minute there were gaps to fill in the program. There was a classical Greek show as well as a planned Egyptian show.

DC I spoke with Perry Rathbone about that. Maybe it was George Seybolt (chairman of the board of trustees). I'm not sure.

First they were going to put the exhibition in the DD Galleries. Which is the student galleries. I said "no." If you do that I for one am not going to show. And we will picket you. There were artist friends of mine who were ready to do exactly that. It would not look too good during the centennial year. The title precluded upon the museum's 100th anniversary. In those hundred years there was no appreciable African American art there nor had there been exhibitions.

CG It was also historically true that contemporary art was not represented. Not just African American art. Other than Brahmin painters the arts of the immigration generations, such as the Boston Expressionists, were not represented in the collection.

DC You don't want to do that Charles. It's the same thing people are doing when it comes to Ferguson. When it's said that cops are killing black men it's said that well, cops are killing white men too.

CG The MFA had no strategy for contemporary art until 1971 when Ken Moffett was hired as curator. In addition to your protests there were also protests from the Boston Visual Artists Union as well as the Dada action of artists sabotaging the museum with the event Flush with the Walls. I was an advocate for change through my column in Boston After Dark. There was a broad spectrum of artists putting pressure on the museum to show contemporary art.

DC Charles I don't want to be connected with that.

CG You don't have to be. I'm just setting the record straight.

DC You're setting your record straight. It has nothing to do with my record. I'm talking about what was happening with black people. I don't want to get bunched up with what was going on in the white community. I was no part of that at the time. What you're doing is a broader view of everything.

CG Ok, Is that good, bad or indifferent?

DC Not if you're African American. That's what European Americans always do. We tell them about our pain and then they want to include it in their pain. No. It's a different story. So please don't do that.

CG What you say is clear to me.

DC Then you're going to do what you do. You always have.

CG How do you feel about that?

DC What you doing what you always do?

CG Yes. Please.

DC It makes me very angry. It always has. Through the years part of my struggle with you has always been this business of you having some kind of larger vision about what's going on in the world. And somewhere in there you include us. It's a very kind of imperialist view, as far as I'm concerned.

CG You might as well add Colonialism. Imperialist/ Colonialist and post modern. Why not?

DC Ok I'll add that too. Yeah, pretty much.

CG I can live with that. Frankly it doesn't concern me because regarding journalism and art criticism there's a mandate to step back and take a broader overview. It's what we do. Our role is to report and evaluate rather than to advocate and take sides. We present facts and it is up to the reader to decide. We try to present the whole picture and connect the dots. Including the disenfranchised as a part of that dialogue.

DC Oh you are still the same amusing fellow you've always been.

CG I've always liked you too.

DC Yeah. I can tell. I still remember the things you wrote about my work.

CG Do you want to discuss that?

DC If you're going to include me and us in a broader view please include the fact that I personally do not want to be included in your broader view. I say that very clearly. I do not want to be included in your broader view. I think it's exactly what you said a nice Colonialist point of view. A point of view of including us in the broader picture of disenfranchised blah blah blah.

CG Looking at your work in the context of the late 1960s and 1970s, and what mainstream critics knew of African American art at that time, your work and imagery for that era may be viewed as emblematic.

Since then, obviously, there have been enormous changes. Today there are a number of A List African American artists; Kara Walker, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Glenn Ligon, Ellen Gallagher, Nick Cave, Fred Wilson, David Hammons, Isaac Julian, Maria Magdalena Campos Pons, Kerry James Marshall to mention a few. On a global level there are the British artist Chris Ofilii and Yinka Shonibare as well as the African El Anatsui. In New York the Jack Shainman gallery represents leading African American as well as African artists.

There are a number of African American and African artists who are very successful in the mainstream art world.

DC The operative word is "since then." During my time there were not a lot of successful African American artists in America. They were beginning to see success but I would tend to say was because of those of us who struggled against the museums and galleries. People like Benny Andrews.

CG I knew Benny well and he was a friend. He was included in my show at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum called "Kind of Blue." There were four artists Benny, Bob Thompson, Emilio Cruz and Earle Pilgrim. The show moved to Northeastern where we held a colloquium with you, Barry Gaither, myself and Pat Hills. The then Yale graduate student Judith Wilson attended. (With Thelma Golden she co-curated the Bob Thompson show at the Whitney Museum.)

Since that era we are talking about I have gone back and looked at historical artists starting with Henry Ozawa Tanner, Horace Pippin, Jacob Lawrence, Charles White, Romare Bearden, the Harlem Renaissance. There are always new areas of interest and study which is a part of the Imperialist/ Colonialist, Post Modern overview that you strongly object to. I have looked before and after the protest years. So I'm not ignorant of African American art, music and culture.

DC I didn't say that. I didn't come close to saying that. To say that you are knowledgeable about American and European art, and to have an overview of that. Of course you are. That's your field. I would expect that. Yes you have entered the African American art field and done some things. Yes. That was not what I said. It's what you heard but not what I said. I said the viewpoint in terms of this particular time is a very kind of Colonialist view. Including us in the whole vast realm of change that came about from around that time. Of which the people you just mentioned were a part. But they did not enjoy the kind of success that subsequently was enjoyed.

Charles White was one of the major artists. He was well known in the African American community but much more well known later. He became major in the American art community. The same with John Wilson (the Boston artist was the subject of a major MFA exhibition) and Calvin Burnett. They got much more play after this so called revolutionary struggle.

It's like what's happening in Ferguson. There was leadership there prior to that but it is now getting national attention. National attention brings change. There wasn't any national attention prior to that.

CG Let's not forget Alan Crite.

DC Oh I would never forget Alan.

CG He was seminal to the Boston artists community. Boston had a rich jazz history. Harry Carney and Johnny Hodges from the Duke Ellington band came from here. There were the after hours spots like the Pioneer Club. Copley Square had Storyville, Mahogany Hall, The Stables and further down Huntington Avenue the Brown Derby and High Hat. In Roxbury there was Estelle's and Connelly's. Sam Rivers and Tony Williams grew up here. There were great white players like Herb Pomeroy, Serge Chaloff, and Dick Twardzik.

I remember going to Storyville and being struck by the walls being painted in arcs of Black, Brown and Beige which quoted a famous Ellington tune. At the time it was remarkable to see a mixed audience listing to the music. That changed later and you saw few black folks at jazz clubs and concerts. Something happened.

DC I was probably in the crowd somewhere.

CG These are complex cultural issues. I don't think we should engage in thumbnail catch phrases like Colonialism. We don't need labels. They get in the way of taking a deep look at what was really going on. What were our roles in all of that?

DC Fine. That's how you see it. You see yourself as living in a larger world. I'm seeing it from the other end. I'm talking as one of those artists who was not a part of the American Scene and that's fine. African American artists of that time were not a part of the American Scene if you are doing a historical thing.

We were not a part of that scene and then subsequently were. If you're doing a historical piece that's the aspect I'm interested in talking about. That we would be the catalyst for all of those artists you mention. The Walkers and all those folks. Subsequent to where we were at that time. A lot of them would be much better artists than we are. There is a richer world history that now includes the African American experience. We are very happy and proud of our role in that respect. We were the artists of the moment even though our work was not of the caliber of later artists. We knew that we would be seen as the revolutionaries of the last century. All of that kind of stuff. We knew that. We looked forward to and saw Carrie Weems and all the other folks who came after. Their fame grew as the result of the things that we did. Because it was no longer unusual to have African American artists in shows.

CG To what extent were the social realists of the 1930s an influence on your work? Jacob Lawrence would be a part of that. But also artists including Ben Shahn, Philip Evergood, Robert Gwathmey. One could talk about a broad spectrum of artists including Jewish immigrants dealing with the Great Depression, social and economic inequity. They were on the front lines of dissent and protest. As a protest artist do you have an empathy or attraction to their work?

DC Why must I?

CG Because of an affinity with what they were trying to achieve in their work. They were using their art to express social and political concerns. There is the art historical term The Concerned Artist.

DC Their social and political concern was not for black people.

CG Is that the only thing that interests you?

DC I'm interested in correctness. If you want to talk about a subject let's be correct about it. It doesn't mean that I wasn't interested in their work. I was interested in Picasso, Cezanne and a whole bunch of other folks as well. They weren't interested in black people. They were interested in African art and to use that as a tool to change how European art was expressed when it came to figurative art.

CG How would you respond to Ben Shahn's works on Sacco and Vanzetti?

DC I would have responded better if he had done work on lynching in the south.

CG Shahn traveled and photographed in the south as a part of the Farm Security Administration program during the Depression. He made compelling images that dealt with racism. He was an artist expressing a broad range of concerns.

During the time when Jan Fontein was director I recall a demonstration and protest in the lobby of the MFA. Is that true and what were the circumstances?

DC It's true. It was around presenting a kind of history of American art.

("A New World: Masterpieces of American Painting 1760-1910" The Museum of Fine Arts, September 7 to November 13, 1983, The Corcoran Gallery of Art, December 7, to February 12, 1984, Grand Palais, Paris, March 16 to June, 1984. Organized by the MFA. curated by Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., Carol Troyen, and Trevor F. Fairbrother. With essays by Pierre Rosenberg and H. Barbara Weinberg. )

It was a long time ago and I'm trying to remember the name of the exhibition. I think they did not include any African American, Asian American or Native American art in the project. It was all white American art. There was a protest and I think it was pushed by Ed Strickland. We were addressing including African American artists and I believe we were speaking to other inclusions of people of color. I don't remember that happening. I think it included a Henry Ozawa Tanner. (A Tanner was added but not included in the catalogue which had been printed by then.)

CG Can you recall some of the artists you were interacting with in the late 1960s and 1970s? Who are the individuals we should be aware of?

DC John Wilson and Calvin Burnett. Calvin was interested in being more active in social statement. I was doing a lot of stuff with New York artists like Benny Andrews. It's hard to remember it was a very long time ago for me. We are not young.

CG (laughing) May I ask your age?

DC 74.

CG Same here. Born in 1940.

How did African American Master Artist-in-Residence Program (AAMARP) start?

DC In 1973 my studio at 15 West Brookline Street in the South End was destroyed. I went on vacation and when I was away someone broke in and stole my artwork and everything they wanted. They scattered my works around the neighborhood and hung some of my paintings on the walls of the playground. They ripped up the paintings and I found pieces of them scattered all around.

The work at that time was very pointed and sharp. I don't know how people knew that I was on vacation. My suspicion was that it was part of all the foolishness that was going on at that time related to black people. Can I prove any of it? No.

CG Who do you suspect for doing this? Was it white people? Was it an act of vengance? I am trying to get an understanding.

DC If you're asking me if I feel that's what was happening the answer would be yes. Can I prove it? No. Did some other folks from the community run through there too? Yes. They left the doors open. So when I walked in I had to kick some people from the neighborhood out of the studio. They were stealing my artwork. The doors to my studio were wide open.

Somebody turned the water on in the basement which was flooded. So that destroyed all of the artwork I had stored there.

CG Can you quantify what was lost?

DC I would say a good 80% of what I did.

CG Jesus!

DC That's what I said and a few other things believe me. That was 1973. A couple of weeks later somebody came by and burned the building down.

It was a very unpleasant experience on one level. On another level it was a great learning experience. After that I was no longer subject to the idea that art was immortal. Nothing is immortal. Anybody's stuff can disappear at any point.

CG You were a prolific artist.

DC I was and still am.

CG What is the work since then?

DC Still pretty much in the same vein. I have three to four hundred paintings. I have close to a thousand collages.

CG We are both 74 and have concerns about our legacy. Are you giving thought to preserving the work through your heirs?

DC My daughter is very good at archival kinds of work. She put a Facebook page together for me. She's working on becoming my agent.

CG Do you have a gallery or agent?

DC No.

CG Have you had success in selling your work?

DC Absolutely not.

CG You have an extensive exhibition history including important museum shows. In addition to the centennial show curated by Barry Gaither you were shown at the MFA by Amy Lighthill, You were included in the DeCordova survey and publication of Boston Painting.

DC The DeCordova bought one of the paintings which were in that show. The MFA had a print of mine in that recent book they did.

(Common Wealth: Art by African Americans in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MFA Publications, 256 pages, $50, January 2015. by Lowery Stokes Sims, the William and Mildred Lasdon Chief Curator o the Museum of Arts and Design and former president of the Studio Museum of Harlem, along with contributions by Dennis Carr, Janet L. Comey, Elliot Bostwick Davis, Aiden Faust, Nonie Gadsden, Edmund Barry Gaither, Karen Haas, Erica E. Hirshler, Kelly Hays L'Ecuyer, Taylor L. Poulin, and Karen Quinn.)

The print was a part of a gift to the museum from an anti war group. They never purchased any of my work. (That later changed.)

CG How did the destruction of your studio lead to AAMARP?

DC I needed a studio space. I talked with Greg Ricks who was the dean of students. At the time he was the head of the African American Studies program.

(The John D. O’Bryant African-American Institute was formed after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.)

Northeastern had these huge factory buildings. They hadn't yet done anything with those buildings. They tore down a lot. Part of one of these buildings housed the African American Studies Department. When I talked to Greg he promised to get me some studio space in the Institute and he gave me a room. I thanked him and put all of the stuff I had managed to salvage in that room. I filled it from top to bottom. When he looked in the room things fell on him when he opened the door. I said "Well I need a little more room." He asked "How much room do you need?" I said "Well I could use the building." He looked at me like I was crazy. The building was on four levels and I was capable of filling it with all kinds of art work and stuff.

He tried to get me some space in the African American Studies Department on the fourth floor on Leon Street. They weren't able to offer me anything that was suitable for what I was doing.

Eventually he invited me to take a look at a space on the second floor. It was about 8,000 square feet of factory space. It was for fabrics so there were old sewing machines and a bunch of other stuff. I said "Give me the key." He said "We have to clear it out first. It will take awhile before you can move in." I said "Why can't I move in now."

If you remember that space it had an elevator that opened up on my floor. So you could move stuff in and out. In the summertime I had 14 hours of daylight.

CG I remember a lot of plants. It was like a jungle.

DC Yes I did. I loved every minute of that.

CG Was it rent free?

DC Yes. I got that space in return for teaching a course in the African American Studies Department. I was available for students to come and talk about art and explore my studio. That's what led to AAMARP because it was on a floor of a building that had 32,000 square foot space. I presented a proposal for the creation of an African American artists complex that would have studio spaces and galleries as well as a community space for all kinds of events. The community space was about 4,000 square feet. It's still there but not in that building. It's at 76 Atherton Street on the Roxbury side of the old Jamaica Plain.

CG Tell me about the fellows.

DC I started off with 13 or 14 fellows. Ellen Banks.

CG I knew her well and have one of her paintings. It was in exchange for a catalogue essay.

DC Me of course. Milton Derr.

CG Sure. I wrote a catalogue essay for one of his Northeastern exhibitions.

(There was a gallery in the library which was later discontinued. That's where we moved the "Kind of Blue" exhibition from Provincetown working with Professor Myra Cantor. I also wrote a catalogue essay for one of her exhibitions of portraits.)

DC Tyrone Geter. Reggie Jackson, Arnold Hurley, Jim Reed, Rudy Robinson, Barbara Ward, and Teresa Young. These artists were actually in residence. Calvin Burnett and John Wilson were associate artists who had their own space. They were connected and exhibited with us whenever we had shows.

At AAMARP we had shows of everybody's work. In the years that I was there as director we did over a hundred exhibitions. There was a whole series we did on Irish art. We did a show based on Irish cartoons in the 19th century around the issue of the Irish and black discrimination. I can't remember the name of the show but it was part of all that. There was somebody Nash who was a cartoonist in those days.

CG Nast. He did the cartoons about Tammany Hall.

(Thomas Nast, September 27, 1840 – December 7, 1902, was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon". He was the scourge of Boss Tweed and the Tammany Hall political machine.)

DC That's the show we had with all of his cartoons.

CG That's what I was asking you before. Your relationship with the art of social protest. What for example was your relationship with Arnold Trachtman?

(Trachtman, (died in 2020 qt 89) a graduate of Mass Art, was a leading protest painter in Boston. When a show of his Vietnam paintings was shut down at Harvard, working with ICA director Drew Hyde, we moved the show to the ICA building in Brighton. Like Dana and myself he showed at the Community Church Art Center in Copley Square which was devoted to activism in the arts. Arnold showed with Galatea Gallery in Boston's South End. His estate is represented by Childs Gallery.)

DC Arnold was one of my favorite people.

CG Ok. Now we're getting somewhere.

DC In my opinion he is one of the great social protest painters. What's happened to him?

CG He's now on in years (older than Dana and myself). Mark Favermann has reviewed his recent shows for Berkshire Fine Arts. I have worked with Arnold over the years as has Pat Hills (Boston University professor emerita).

Moving on what can you tell me about the recent donation of African American art to the MFA from the Axelrod collection?

(Sixty-seven works by African American artists have recently been acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, from collector John Axelrod, an MFA Honorary Overseer and long-time supporter of the Museum. The purchase has enhanced the MFA’s American holdings, transforming it into one of the leading repositories for paintings and sculpture by African American artists. The Museum’s collection will now include works by almost every major African American artist working during the past century and a half. Seven of the works are now displayed in the Art of the Americas Wing, in time for its one-year anniversary this month. MFA press release 2011)

DC Except for the book ("Common Wealth") I don't know it very well. If I comment on the collection it would be about the art itself. He has a lot of very good pieces. A lot of early pieces from a lot of artists. Most of it is lesser work. I did not see anything that I would consider to be masterpieces.

CG Have you seen the work installed in the MFA?

DC No. I haven't lived in Boston since 2004. I live in Gallup, New Mexico.

CG How did that happen?

DC African American male issues have been ongoing. It sounds like a preamble but it really does relate to what I'm going to say. When I moved here my son was a teenager. He was 16 and the year prior to that he was being courted, sort of, by the Crips and the Bloods.

The courtship went like this. You'll join one or the other of us or we'll kill you. My son was and is, if pushed to it, an extremely good street fighter. If you're 250 pounds and think you're going to kick his ass because he's a little skinny guy, you're in trouble. He's that good.

He would go to Forest Hills and they would meet him with somebody who would challenge him to a fight. He was fighting every day and would come home with a bloody nose, scratches on his face. The other guy? Oh well. He was very good at knocking people out. He told me "If I stay here by the time I'm 16 I'll either be dead or in jail."

Since my life experience included that when I was a teenager I knew exactly what he was talking about. So I said here's what we'll do. I'll retire. I was 63 at the time. We'll move wherever you want. So pick a place. He picked New Mexico because he met a Navajo and he was very heavily into his Native American heritage. We are African Native Americans. From several different families of Natives. We are Oglala Lakota, part of the Sioux family. It was in the Dakotas.

My branch of the family was chased out of America into Canada and ended up in Nova Scotia. That's where my grandmother was born in the 1880s. The Lakota fought the army for many years. When the army got to be more than they could handle the army chased them into Canada and they made their way all over Canada. A number of Lakota people ended up in Nova Scotia.

CG Where does your African heritage come from?

DC My father's side is native and my mother's side is African. From Barbados.

CG Where did your parents connect?

DC A little town called Lynn, Massachusetts.

CG Are you going to write your memoirs?

DC I've written some of it. That will take some time because right now I am trying to get my work together because I want to do a retrospective at some point. The challenge is what everyone has. How to do the retrospective that I have in mind with no money. Like a lot of African Americans I forgot to take care of the money aspect of things.

CG That's true for most artists. Having pursued a career of supporting contemporary art in Boston very little of the work and careers of artists I have written about has made it into the mainstream. Most of the work I have been involved with is slipping off the radar. Which is why this oral history project is important. It is an attempt to preserve aspects of our legacy. When we're gone an important period of our culture goes with us.

DC I would agree.

CG Even though we enjoy a love/ hate relationship there is a nostalgia for it. This has been an important aspect of my life.

DC I enjoy it immensely. You were one of the critics who taught me not to worry about what critics have to say.

CG Thanks so much for ignoring me.

DC Pretty much. You would write your things and I would go, Ok. That's Charlie and I moved on.

CG I was responding to you in two ways. On the one hand Dana Chandler the activist and on the other Dana Chandler the artist. Is it possible to separate them in terms of writing criticism? How to treat an individual who has a prominent profile as an activist and also wants to be evaluated in a formalist sense as an artist. It's hard to unravel and separate out those threads. It becomes a Gordian Knot.

Wearing different hats and taking on multiple roles as critic/ artist/ curator has been problematic for me as well. Because of my profile as a critic there has been prejudice against accepting my efforts as an artist. I was in a group show at the Boston Center for the Arts. The critic for the Phoenix wrote about every artist but me. I asked him about it and he said "You can be either a critic or an artist but not both." So this is an issue for a lot of us with multiple roles in the arts.

DC Whatever my legacy is I won't be here to appreciate it. My children will be here to appreciate it. For me it's hard to get excited about legacies that I won't see.

CG That may be but I feel you have a responsibility to put things in order for your heirs. It's a common issue that I deal with. I get a lot of calls from heirs of estates. And I am reminded that I have to put my own life in order. That's a part of the motive in wanting to talk with you and others who have been key players in a rich but ephemeral cultural history. We are preserving essential information for future generations.

Comment by Edmund Barry Gaither

“"In the course of the two part interview with Dana, mention is made of his artistic legacy, or put differently, how he will be remembered. The Museum of the National Center of Afro-American addresses such questions for black artists that its regards as consequential. Dana is in that group. I have taken a moment to cite some of the ways in which our Museum has supported establishment of his legacy. Here is a list of exhibitions of his work that we have presented, followed by a summary of works that we have acquired and from which periodically works are shown or loaned. Exhibitions jointly presented by the MFA and the Museum, NCAAA: "Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston," 1970 "Jubilee: Afro-American Artists on Afro-America," 1975-76, (five works) Museum, National Center of Afro-American Artists "TCB/Taking Care of Business," 1971 (six works) Also presented at the Currier Gallery of Art, Manchester, NH. "Spiral: Afro-American Art of the Seventies" 1980 (two works) "Recent and Undestroyed Images: Dana Chandler (Akin Duro)," (One-person exhibition) (seventy-three works) "Denial; Reparation Installations and Assemblages: The Art of Dana Chandler," 2003, (One-person show) (five rooms) "The People's Art: Black Murals, 1967-1978" Co-developed with the African American Historical and Cultural Museum (Philadelphia) and presented in both cities. (one work) Exhibition organized by others but presented at the Museum, NCAAA. "Conflict and Tradition: Images of a Turbulent Decade," 1986 Organized by the Studio Museum in Harlem (one work) The Museum has acquired by gift or purchase thirteen paintings by Dana including a very early image of Thurgood Marshall before he was a Supreme Court Justice, and fifty-one posters and prints."