Kendall Messick’s "Blind Sight"

To See and to be Seen

By: Jessica Robinson - Aug 13, 2020

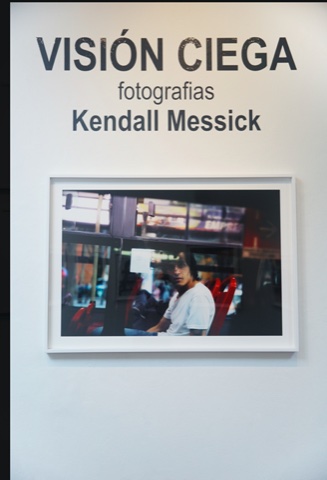

Kendall Messick "Blind Sight"

In October 2019, I was having dinner with my friend Kendall Messick, an artist who creates installations with still photography, film, video and ever-evolving two-and three-dimensional media. That evening he told me he was flying to Bogotá, Colombia, the following day for a major installation of his work titled Vision Ciega (Blind Sight.)

Blind Sight is an achievement of both patience and memory. It was thirty-four years in the making.

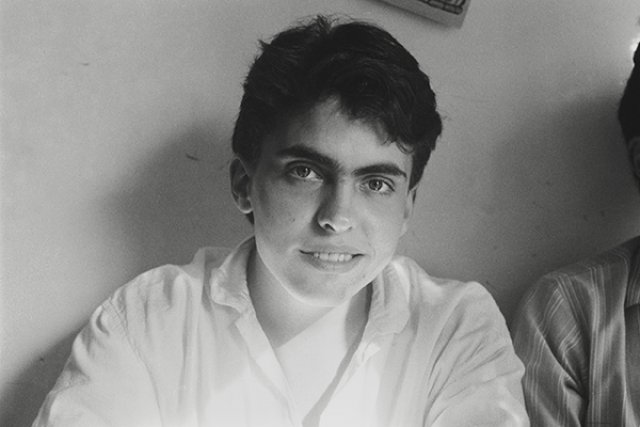

In 1985 Messick left the United States for the first time. He’d won a scholarship to the Universidad de Los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. He was there to study with the prize-winning poet and novelist, Piedad Bonnett. “I did not speak Spanish and my family in Colombia did not speak English, but we established a relationship so deep that I really felt at home. Living in Bogotá was one of the most important experiences I have had throughout my life,” says Messick. “Looking back I realized that Bogotá was the beginning of my life as an artist.”

Messick has come a long way since that realization. In the thirty-four years that he has been an artist he has had four large-scale photographic exhibitions including Corapeake, a series in which he intimately documented the memories of elderly African-American residents using photographs, audio recordings and film. The film was broadcast nationwide on PBS and became a finalist for Input TV, an international screening conference showcasing the best of public television programming worldwide.

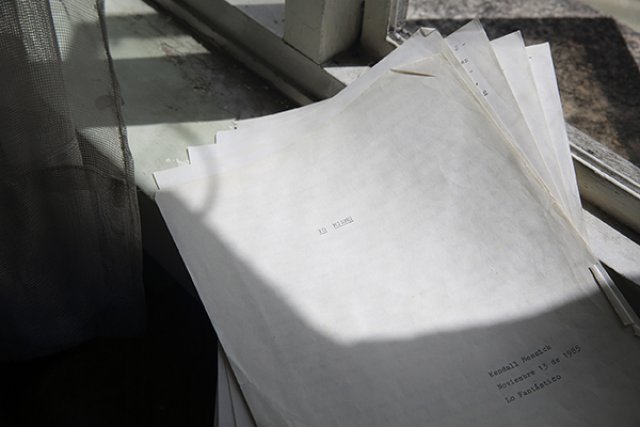

Blind Sight (Vision Ciega) is Messick’s photographic tribute to Bogotá. It marks his fifth major exhibition. The inspiration came in 2014 when Messick rediscovered a short story he’d written for one of his literature classes in Los Andes. The story was based on a dream which he believes was tied to his experience as a gay man living in a conservative Catholic country in the 1980s. Having to keep a portion of his life compartmentalized from his Colombian host family, he asked himself, “Do people really see me? Or do they see this idea of me? At the core of my work is an exploration of memory, intimacy, acceptance and humanity. All my projects begin with something personal,” says Messick.

Blind Sight is deeply personal. It defines the essence of his artistic experience in Bogotá.

Half of the series was shot in 1985, his first year in Bogotá. The second half when he returned in 2013, twenty-eight years later. In the earlier group, shot in black and white, the subjects are looking at the camera. The second group is in color. Here Messick is looking back. The subjects are not. Do they even know he’s there?

With Blind Sight Messick is shifting time, crossing frontiers, reflecting on his younger self. He has become a time-traveler.

The photographic style, in my opinion, fits loosely into the genre known as street photography, meaning, in the broadest terms, ‘randomness,’ or fleeting moments.

As Susan Sontag put it, “The photographer is an armed version of the solitary walker….the voyeuristic stroller.” I say ‘loosely’ because I believe that many of Messick’s photographs from the second half of the series are intentional, not spontaneous.

Fleeting Gaze (Miranda Fugaz) captures the transient moment of a passing bus. A boy in a white T-shirt stares out of a window. He is looking directly at us. Does he know he's being photographed? Messick might have been attracted to the lines and shapes of the window, the arched body, the gaze. Perhaps this is an example of a fleeting, urban encounter. This, then, defines the genre.

Without Title (Sin Titulo) is the sexiest image in the group. A young man looks out of a door frame, his back to the camera. The twisting arc of his neck, the hand that rests on the frame of the door, the naked shoulder, all suggest sensuality. Adding to the physicality is the deep green texture of the door, the light from the window and the shape of the door frame. Did they just meet? Just have sex?

Messick is not a provocateur. For me his pictures evoke stillness and silence. His is a quiet memory.

In the image titled The Church (La Iglesia,) Messick establishes a dialogue between form and light. A woman in a bright red dress is caught in motion, about to enter a church. She is holding something over her head, shading herself from the sun. The picture casts long, dramatic shadows, not unlike a film noir scene. She seems to be walking slowly. Almost frozen in the Moment.

“There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. …Oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever,” Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Photographs remember things we’re unable to remember on our own. Where we were. Who we were with. What we were doing. They spark a thought, jog a memory. People photographed probably could not remember these things. The photographer does, having recorded it, but knows little else about the person.

The next time I saw Kendall Messick was November of 2019, a month after our dinner. He’d just returned from Bogotá where his exhibition had received important critical response: “I was on national radio, every major television station and in all the newspapers.” The story doesn’t end here. There is soon to be a limited-edition book which will include additional photographs, as well as Messick’s original short story from his student year in Bogotá.

Listening to Messick’s stories, the narrative of his work, that’s what draws me in. Its range is far and wide. I have only scratched the surface.

A traveling exhibition is scheduled for the United States. Dates to be determined.

Visit Kendall Messick.