Isamu Noguchi: Landscapes of Time

Clark Art Institute

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 24, 2025

Isamu Noguchi: Landscapes of Time

Clark Art Institute

Organized with loans from Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

Curated by Matthew Kirsch and Kate Wiener

Patrons: Cynthia and Ron Beck

Through October 13, 2025

“My awareness of being an American, which came in the fall or winter of 1933, was followed in 1934 by the influence of social consciousness to the extent that when it became summer I decided to move to Woodstock, New York, to do a sculpture on the lynching of blacks. The Marie Harriman Gallery offered to help me prepare for an exhibition of my work, which was held the next year. In this show were models and drawings for the Monument to the Plough, the Monument to Ben Franklin, and Play Mountain besides a few portrait heads. The sculpture Death was shown but Mrs. Harriman declined to show Birth, a large travertine carving I had made following an observation of a delivery at Bellevue Hospital. The show was roundly denounced by the art critic Henry McBride.” Isamu Noguchi

The artist, of mixed heritage, endured a lifetime of racism, rejection and adversity. Beginning in February 1934, Noguchi began submitting his first designs for public spaces and monuments to the Public Works of Art Program. One such design, a monument to Benjamin Franklin, remained unrealized for decades. Another design, a gigantic pyramidal earthwork entitled Monument to the American Plow, was similarly rejected, and his "sculptural landscape" of a playground, Play Mountain, was personally rejected by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. He was eventually dropped from the program.

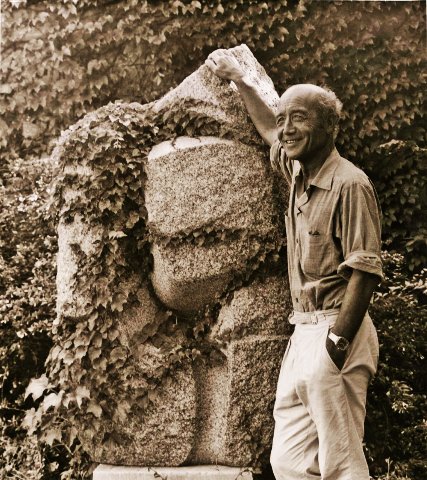

Today he is regarded as one of the notable artists of his generation. The 32 works comprising Isamu Noguchi: Landscapes of Time at the Clark Art Institute provide an elegant, diverse and tantalizing glimpse of his invention and originality. In addition to the sculptures on view he was a landscape architect, furniture designer, and collaborator with the dancers Martha Graham and the team of dancer Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage.

The exhibition has been exquisitely installed in the light-drenched 3,200-square-foot glass Michael Conforti Pavilion designed by Tadeo Ando. There is divine synergy of container and contained. Bathed in natural light the pieces are augmented by vistas of the reflecting pool and uniquely manicured landscape of the Clark.

Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) was born in Los Angeles, the son of Yone Noguchi, a Japanese poet who was acclaimed in the United States, and Léonie Gilmour, an American writer who edited much of Noguchi's work. He abandoned her and returned to Japan.

In 1906, Yone invited Léonie to come to Tokyo with their son. At first she refused, but the two departed from San Francisco in March 1907. Upon arrival, their son was finally given the name Isamu ( "courage"). However, Yone had married a Japanese woman by the time they arrived, and was mostly absent from his son's childhood. After again separating from Yone, Léonie and Isamu moved several times throughout Japan.

In 1912, while the two were living in Chigasaki, Isamu's half-sister, a pioneer of the American Modern Dance movement, Ailes Gilmour, was born to Léonie and an unknown Japanese father. Léonie had a house built for the three of them, a project that she had the 8-year-old Isamu "oversee." Nurturing her son's artistic ability, she put him in charge of their garden and apprenticed him to a local carpenter.

In 1918, unaccompanied Noguchi was sent back to the US for schooling in Rolling Prairie, Indiana. After graduation, he left with Dr. Edward Rumely to LaPorte, where he found boarding with a Swedenborgian pastor, Samuel Mack. He graduated from La Porte High School in 1922. During this period of his life, he was known by the name "Sam Gilmour."

He enrolled to study pre-medicine at Columbia University but that didn’t last long. His mother, who returned to the States, encouraged him to take evening art classes which he soon pursued exclusively. He apprenticed with Gutzon Borglum the sculptor of Mt. Rushmore. In the studio he did odd jobs and posed for figures. What little he did learn was from Italian bronze casters who worked for Borglum. Later, in Paris, he interacted with other artists and for a time assisted Brancusi whose influence is evident in his work.

While his exhibitions provided few sales he prospered as a portrait sculptor. During the Depression, however, there were few wealthy clients. It would have been insightful to have a portrait in the Clark exhibition. He made enough to travel extensively in Europe, India and Japan where he had a diffident reunion with his father. In Mexico he had a brief, intense affair with Frida Kahlo.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese sentiment prevailed. In response Noguchi formed "Nisei Writers and Artists for Democracy." Noguchi and others wrote to the congressional committee headed by Representative John H. Tolan. He later attended the hearings. He helped organize a documentary of the internment, but left California before its release. As a legal resident of New York, he was allowed to return home. He hoped to prove Japanese-American loyalty by contributing to the war effort. Noguchi met with John Collier, head of the Office of Indian Affairs, who persuaded him to travel to the internment camp located on an Indian reservation in Poston, Arizona, to promote arts and crafts and community. Arriving in May, 1942 he was the camp’s only voluntary internee.

His hope was to design parks and recreational areas within the camp. Although he created several plans including baseball fields, swimming pools, and a cemetery, the War Relocation Authority had no intention of implementing them.

Visiting this exhibition entails two approaches. The first is to wallow in the luxuriance of the whole. There is an immediate and visceral impact; particularly a cluster of his familiar, signature Akari Light Sculptures. Although he created them in various scales and shapes here is a grouping of round practicals defining the center of the exhibition. From this initial impact a visitor proceeds to the sum of its parts. In this instance, very diverse works some as tiny as thumbnails all demanding individual attention.

At the entrance of the gallery is a box with an unpaginated brochure illustrating and labeling all of the pieces on view. It is very generous of the Clark to provide this extensive publication free of charge.

I worked my way around the circumference stopping to view and photograph each piece. The work was diverse- some of it readily familiar- and others not. This was particularly true of a number of surrealist inspired works from the 1950s; My Mu, Skin and Bones and Ghost. They evoked comparison to Giacometti and Arp.

The maquette Bell Tower for Hiroshima with a cluster of vertical posts and ceramic elements in particular evoked The Palace at 4 A.M. (1932) by Giacometti. In an exhibition related to the project, on a blackboard on one wall of the gallery, Noguchi drew a fallen temple bell in flames and inscribed it with lines from a poem by his father, “Kane ga naru” (“The Bell Rings”):

The bell rings

The bell rings

This is a warning!

When the warning rings,

Everyone is sleeping.

You too are sleeping.

The project was rejected as inappropriate for an American artist. An American project was rejected for the same reason in reverse. Paradoxically, the artist was not Japanese enough to memorialize Japan or American enough to represent the United States. Similar arguments were made when Maya Lin won the competition to create the Vietnam Memorial for the Mall of Washington, D.C.

There were other surrealist works Remembrance (Mortality) (1944), The Seed (1946, fabricated c. 1979), and several tendrils suspended from a square platform Mortality (created 1959/ cast 1965).

The more familiar works entailed carvings in stone and wood. Like Michelangelo he created works with finished, polished use of the material and parts untouched in their natural state. They recall the unfinished sculptures in the Academia for the unrealized memorial to Julius II. Inspired by Neo Platonism he spoke of finding the figures and bringing them out from the stone.

In a very refined manner there is a similar approach to Origin (1968, African granite). It is a medium scaled, rounded form with a polished top and chisel marks evident below. The riveting simplicity of piece is utterly divine. Slightly more topical is Lunar Table (granite 1961-65) which in a reductive manner defined the cratered surface of the moon. He specifically references space exploration with Re Entry Cone (Swedish granite, 1970). It is a mimesis transposing an artifact (space capsule) into an art object and sculpture. The artist poetically has us consider the dichotomy of form and function. It’s typically subtle and I wonder how many visitors “get it.” The work takes more time and consideration than that of most visitors I observed who were more interested in selfies and shooting each other than absorbing the experience.

The most riveting piece, truly worthy of time and attention, is the iconic “costume” he designed for Martha Graham’s 1946 “Cave of the Heart.” It is a wired Spider Dress worn by the vengeful Medea who murdered her own children as well as the intended bride of her husband Jason the leader of the Argonauts. The “costume” is mounted on a carved “serpent.” Donning a metal garment of flame-like spikes, she becomes symbolically trapped in a prison of her imagining.

It was glorious to view this iconic work set against the panorama of light and the Clark’s reflecting pool. Truly it was a dazzling, palpable means of extracting and absorbing the essence of an astonishing masterpiece of modern art.