Dishwasher Dialogues, Genius of Bread and Books

Under the Mountain

By: Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Sep 24, 2025

Under the Mountain

Rafael Mahdavi: Bread was something we could always afford. You would say you had your baguette, for a few days at least. A baguette a day kept me fed, a little constipated too, the staff of life. Maybe that’s pushing it. A baguette in hand, I could walk into an épicerie and buy some slices of ham, or in the Latin Quarter I would stuff a sizzling merguez into half a baguette, and that was a good meal.

Greg LIght: Yes. The good life was richly enhanced by the baguette. And its luxuries. Like butter. Oh, the butter. A fresh baguette with Parisian butter? That’s a four-star meal in itself. Throw in the ham, the cheese, and the merguez? A self-indulgence that makes me salivate, even as I write 45 years later.

Rafael: There was even a baguette painted blue in the Museum of Modern art, a piece of Dada art by Man Ray. Baguettes become as hard as wood, a baked baseball bat, it could be used as a weapon.

Greg: I like Man Ray even more now.

Rafael: Bit of trivia for you. His real name was Emmanuel Radnitzky.

Greg: Fantastic name play. As in his work, too. Especially his film Retour de Raison, which was anything but. I think Leroy had a sketch or doodle of his on a napkin. Painting a hardened baguette blue may have been a step too far. A rigid baguette is still recoverable, no matter how hard. And, as pain perdu—French toast—it is almost as good. If it’s breakfast, sometimes even better. It does deserve to be in a museum, whatever the color. Talking about sealing and painting everyday objects, are you going to mention the object we sealed and painted and sent out to announce your first one man show in Paris?

Rafael: I’ll get to that show later. Bakeries first. I’d go into a boulangerie to buy a baguette, and since I was always hungry, especially on Sundays around noon, buying only a baguette was hard.

Greg: Yes, maybe not such a good topic while talking about bread.

Rafael: In French bakeries––my God, what a display––my eyes wandered over the sparkling glass shelves with all those pastries on show, so many shapes and sizes and flavors, the Paris-Brests, the pains aux raisins, the croissants aux amandes, and the congolais. Ah, those were the worst, a pure sugar high, the best thing to have when you got the munchies after smoking a joint. The congolais was a conic shaped, little mountain of ground coconut and a lot of sugar, and there were the palmiers too, financiers, and the madeleines.

Greg: And you told Don you were not much into food? Sounds like your eyes were well schooled.

Rafael: Yes of course, I knew of Marcel Proust and his damn madeleines. When I ate one, I thought I was eating a pastry full of chopped letters. Good old Marcel, under the guise of literary literature, he was the greatest gossip of all time, une sacrée commère, celui-là.

Greg: On those few occasions, when finances permitted and gastronomic desires insisted, I drifted towards the savory items on the shelves. Sugar rarely called to me like a good croque monsieur or, even better, a croque madame. Essentially versions of a toasted cheese and ham sandwich. But what versions they were! Someday I will peruse Proust for references. Or Balzac or Sartre. Did they eat croque monsieurs and admit it? Surely, Camus must have.

Rafael: The point I’m trying to make here is that you might go into a bakery for a baguette, and I’ll add here that I liked mine pas trop cuite, that is to say underdone, like steak tartare, baguette tartare, because these were less crispy. I thought for some reason that if the baguette was under-cooked, I could taste the dough better, there was less burned stuff, and it was more nutritious; the burnt dough was useless and hard on the gums.

Rafael: To walk out of a Parisian bakery with only a baguette is hard to pull off, especially if you’re hungry. You pay for the baguette, and as you’re leaving, you turn around and say I’ll take a croissant aux amandes too. Damn!

Greg: Somehow, an under-cooked baguette sounds sacrilegious (sacré bleu!) to me. I have no memory of having eaten one, or an over-cooked one for that matter. Not that I would have thrown it away. Not then. Not even now. And now I can afford to. I will grant you the point about les croissants. A wonderful, wonderful treat. Especially with a café crème. Although, back then, the cost-to-calorie ratio was a bit high to make them a regular part of my day-to-day existence. Baguettes, on the other hand, came very close to matching the pleasure of a carte orange. They, too, were affordable. And supported life. Even when they came after an almost Ionesco-like dialogue.

Greg: Not long after I moved into my two room chambre de bonne flat, I found a nearby boulangerie that served fabulous baguettes. It was the closest and the first one I went into. To me, all boulangeries in Paris served fabulous baguettes. Anyway, every morning, I went there for my baguette, usually stood in line for a few minutes, would then be summoned for my order: “Monsieur?” and the following exchange would happen. Day after day after day.

Server: Monsieur?

Me: Une baguette s’il vous plaît.

Server: Deux?

Me (speaking my syllables slowly) Non, une seu-le-ment.

Server (wide eyes) hands me a single baguette and I give her 2F10.

Greg: This must have happened a dozen times. Usually, the same server but occasionally a different one. Never a smile. Maybe it was too busy, or this was just Paris?

Rafael: Paris was a tough city; it could be cold and mean and rude. You didn’t get many breaks, that was why Leroy was such a rarity. We all have heard of the proverbial neighbor on your floor. You can live for years on the same floor and all you’ll ever get, if you get it all, is a cold bonjour from the person across your landing. There are exceptions, of course, but not many.

Greg: This incident was more cool eccentricity than cold rudeness. The boulangère always asked me if I wanted two after I ordered one. And each time, for a moment, as they handed me the baguette, they looked at me as if I was borderline insane. It was a daily conundrum that baffled me for months. You finally solved the puzzle when you waited with me one day while I got my morning baguette. We went in and on cue, the exchange happened. I just shrugged at you—what’s up with that? As we left, you told me the problem was my French pronunciation: my une was incomprehensible, and my seulement sounded like sous-le-mont, as in under the mountain. As if I was suggesting a romantic tryst on a quiet hillside. So, what transpired was:

Server: Sir?

Me: (something) baguette please

Server: two?

Me: No, (something) under the mountain

Greg: It was a wonder I was able to buy anything to eat at all. She probably thought it was American slang for sex.

Rafael: The thing about boulangeries is that the women running the bakery, the boulangères, were always good-looking, well-dressed in crispy clothes, and their aprons had traces of flour.

Greg: She was cute. There was a reason I kept going back.

Rafael: The same thing was usually true with pharmacists and coiffeuses. I’d see them through the window, but I never went into a coiffure salon.

Greg: Attractive and intimidating was a lethal combination?

Rafael: I cut my own hair with a comb-like instrument with a razor blade, and depending on how you set it, as you pulled this thing through your hair, it cut it at the desired length. I saved myself quite a lot of money. I never had anything dry-cleaned either; it was too expensive, and I did my own sewing also, buttons too and even zippers.

Greg: But not as lethal as being broke?

Rafael: With that and what we saved on baguettes and the carte orange––what did we do? We bought books, usually second-hand books, at Shakespeare and Co. on the left bank, across from Notre Dame. Sometimes we bought new books at WHSmith on Rivoli, or at Brentano’s near the Opera. How to explain this? Baguette and carte orange dovetailed into reading and literature. Books were what we cared about.

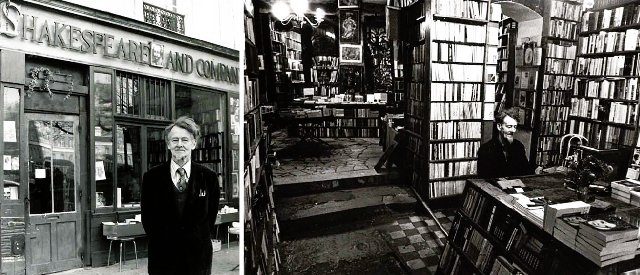

Greg: Bread and books. Two more essentials. Shakespeare and Co. will always be dear to my heart. The first real bookstore to sell my book of poetry. And to host a reading I gave there. George Whitman, the founder, was a dedicated and friendly guy. I remember him as being serious about what he was doing. Creating a place for writers and artists to hang out and do what they do.

Greg: Along with the big literary names who passed through— James Joyce, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Anaïs Nin, William Styron, Henry Miller, Lawrence Durrell, James Baldwin—hundreds of young writers made the pilgrimage as well. George was remarkably open to selling small press editions of their poetry and other writing. Such as ours.

Greg: One Christmas I gave every one of our Chez Haynes company of friends and artists books which I bought there. It made Christmas shopping easy that year. A dozen or so volumes of poetry by young, lesser-known poets who lived under the mountain of celebrated names, and who had graced Shakespeare and Co. over the previous two and a half decades since its opening in 1951. Most of the books were covered with dust and curled up at the corners—each one different, and each one with a story of poems to share.