Rev.23 Farce of an Opera

Comedy Based on Book of Revelations Nothing to Laugh Over

By: David Bonetti - Oct 03, 2017

Rev.23: A Farcical Hellish Opera!

A World Premiere

Music by Julian Wachner

Conception and Libretto by Cerise Lim Jacobs

Stage Director: Mark Streshinsky

Conductor: Lidiya Yankovskaya

Costume and set designer: Zane Pihlstrom

Lighting designer: David Reiffel

Choreography: Yury Yanowsky

Cast: Lucifer – Michael Mayes, baritone; Hades – Vale Rideout, tenor; Furies – Nora Graham-Smith, mezzo-soprano; Melanie Long, soprano; Jamie-Rose Guarrine, mezzo-soprano; Persephone – Colleen Daly, soprano; Sun Tze – David Cushing, bass-baritone; Adam – Jonathan Blalock, tenor; Eve – Annie Rosen, mezzo-soprano; Archangel Michael – Michael Maniaci, counter-tenor;

John Hancock Hall, Boston

Sept. 29-Oct.1

Last year at this time, Cerise Lim Jacobs’s White Snake Projects (by a slightly different name) put on the Ouroboros Trilogy, a day-long extravaganza of three 100-minute long operas. Each opera was the work of a different composer tied together thematically by Jacobs’s own libretti; the trilogy was a mash-up of Asian philosophies and myths with a sprinkling of western ideas. It explored the concept of the circularity of life and history, the endless repetition that T.S. Eliot addressed in his Four Quartets: “We shall not cease from exploration/And the end of our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time.” Visually beautiful – often stunning - and musically rich with a cast most regional companies can only dream about engaging, it was a triumph of ambition and taste. One of the operas, Zhou Long’s “Madame White Snake,” presented separately a few years earlier, had won the Pulitzer Prize in music in 2011. Boston hadn’t seen or heard anything like it before, and it was exciting to think about the four additional operas Jacobs promised to present yearly through 2020.

Well, expectations exist to be knocked down, and I can only wonder, ‘what happened?’. “Rev. 23” – its subtitle “A Farcical Hellish Opera!” an unsubtle clue to its nature – is ostensibly the final, never written book of “Revelations,” the Bible’s final chapter, in which Paradise is lost, won, and lost again – or something like that. The seriousness of the theme is unconducive to farce, which is best devoted to bedroom politics rather than eschatological themes. To say that the opera and its realization on stage is cartoonish is not criticism – it is the stated intention of its creative team. OY VEY! I don’t like graphic novels either.

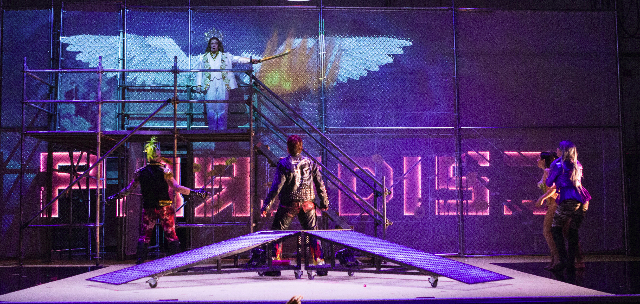

There is much to praise about “Rev. 23” once one doesn’t think too much about what it’s purportedly about. The production looks good – as in the “Ouroboros Trilogy” no expense seems to have been spared – and much credit for its success goes to the production team, especially stage director Mark Streshinsky, who did his best to make the frenetic action coherent, costume and set designer Zane Pihlstrom, whose unit set, chain link fencing and industrial scaffolding, with a giant neon sign spelling out “Paradise” above it all, served well for both Paradise and Hades, and lighting designer Lucas Krech made the transitions from dark to light happen smoothly.

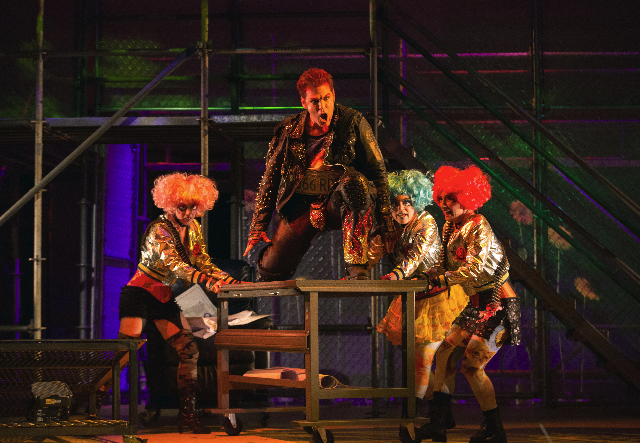

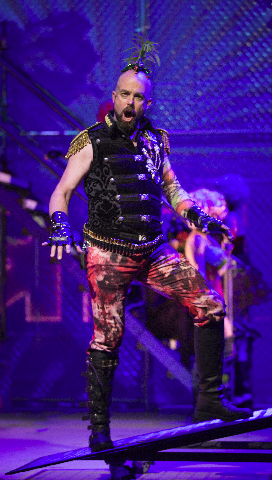

Pihlstrom’s costumes were witty takes on punk appropriate to the characters’ cartoon origins. Lucifer, the burly, brusque Michael Mayes, looked like a road warrior out of Mad Max, with a sequined cod-piece he repeatedly thrust at the passing scene. As Persephone, the attractive young Colleen Daly seamlessly went from sporting soignée lounge wear to distressed biker-chick gear. As Lao Tze, the author of the classic “Art of War,” David Cushing looked as if he stepped off the pages of Marvel Comics. So did Vale Rideout as Hades, and his feathery chartreuse Mohawk gave his character an identity beyond merely being the ruler of the underworld. As the Archangel Michael, Pihlstrom dressed Michael Maniaci in a white suit and crown that made him look like Wayne Newton or maybe Liberace. Pihlstrom gets my award, however, for the Raggedly Ann wigs he gave the three bustier-clad Furies, one each red, pink and electric blue. And exploiting the trend toward near-nudity on the opera stage, Pihlstrom let the denizens of Paradise – mostly the dance corps - wear their own bodies, for the men, with nothing but the tiniest flesh-colored brief, adorned with an orchid on the place of their generative organs. As Adam, tenor Jonathan Blalock, who has a physique to marvel at, might not have sung very well, but he compensated with his pecs (not to slight his abs).

Choreographer Yuri Yanowsky gave the dancers more interesting movement than you often find in opera in which dance is not of prime importance; however, his second dance, in which the dancers performed a sort of semaphoric gesturing looked like second-rate Peter Sellars.

The singing was also of a high quality. Mayes did not impress – in fact the reverse – in his previous two appearances in local productions, both the BLO’s “Rigoletto” and “Carmen,” but here as Lucifer his vocal rawness didn’t grate, and I was surprised to hear him float a few sweet high notes. As Hades, Lucifer’s partner in disruption of the established order, Vale Rideout sang with a strong, fluent tenor. Among the three principals, Colleen Daly’s Persephone was the only disappointment vocally. Her thin soprano was stretched as she negotiated high notes, failing to be the seductive instrument the role required.

In smaller roles, bass-baritone David Cushing was as authoritative as we have come to expect from him in his many local performances as Lao-tze, and powerful countertenor Michael Maniaci as the Archangel Michael sang with superb musicianship despite his Vegas strip drag. Mezzo-soprano Annie Rosen as Eve stole every scene she appeared in with her flexible and articulate voice, making a particularly strong impression in her big aria “Blood rubies, burning hot,” and her voice soared over the orchestra and other singers in the finale. Alas, her Adam, the hunky Jonathan Blalock, sang at best like a Broadway tenor, straining for the high notes, voice fading away without a microphone. The three Furies all sang sweetly with great vocal blending.

After the eye and vocal candy, the problems began. Both Jacobs’s text and Julian Wachner’s music were banal, and that’s the kindest word I can think of to describe them. Jacobs libretto seemed to be a grab bag of platitudes looking for a theme. Is It that “to be human is to be flawed”? Or that Paradise obviates corruption, i.e. “Art, Literature, Drama, Opera, Heavy Metal, Pop”? Or both of them and more. Jacobs, whose texts for the “Ouroboros Trilogy” were dense but largely coherent, seems to have thrown everything that entered her mind except the proverbial kitchen sink into “Rev. 23” and then reconsidered and threw in the sink as well. With only 100 minutes, she should have used a large pair of scissors to pare her text and themes, focused on the main story and given her characters some space and time to express themselves.

Most damning perhaps is that an opera termed a farce wasn’t funny.

Wachner’s score followed Jacobs’s lead – I guess he didn’t have any choice since her text was the source of the enormous puzzle of many parts that opera is. Still, Wachner, who is the highly regarded music director of Trinity Church Wall Street, made I think some bad choices here. I’ve listened to some of his music, which has a real sense of lyricism and a strong rhythmic pulse. And an internal coherence. Here he created a pastiche, a little of this, a little of that, a lot of Philip Glass. In his program note, Wachner wrote that his “melodic and harmonic language continues to embrace an omnivorous language,” citing both Lucas Foss and Leonard Bernstein as influences.

The Broadway Bernstein is killer for me. It is true that Bernstein’s Broadway works are among his best and among the best that the benighted form of the musical has experienced since its ‘40s and ’50s heyday, but it provides no good model for an opera today, and in “Rev.23” Wachner resorts too often to its banality and sentimentality. Bernstein’s finale for “Candide,” his masterpiece in the genre, was Wachner’s model for his finale here, but it’s an example of not being able to go home again.

Some of Wachner’s explicit references were amusing – the appropriation of Gluck’s “Dance of the Blessed Spirits” for the dance of the denizens of Paradise, and at one point a piano in the small orchestra, which, by the way, was ably conducted by Lidiya Yankovskaya, played the familiar refrains of Beethoven’s “Moonlight” sonata. His fall-back guy as he is for so many contemporary composers was Philip Glass, and Glass’s motoric arpeggios and rhythms were used repeatedly to get the music going. There were even passages that were reminiscent of John Williams’s film music.

Obviously, none of this was to my taste. Whether it will appeal to future audiences I don’t know, but I suspect that “Rev. 23” will not be soon revived.

Still, hat’s off to Jacobs and her ambition. Her program lists three more specially commissioned world-premieres coming in the next three years, each one going farther and farther into worlds unknown. The next, “PermaDeath,” is termed a videogame opera in which “digital avatars battle it out in cyberspace with the gods of our ancestors in an epic fight to the (permanent) death.” I suspect I might not like it, but it might speak to a new generation of potential opera-goers and that’s what the medium needs. Jacobs is admirably working with Boston City Councilor Ayanna Pressley to provide free tickets to constituencies that have not been touched by opera. It might speak to them in a way it doesn’t to an old fogey like me. Best wishes for her good intentions.