Dishwasher Dialogues the Switch

Utopia and the Universal Smile

By: Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Oct 08, 2025

The Switch

Rafael: I have never possessed the gift of gab, and I was not one for small talk lasting hours and hours. I remember the first evening you came in with two beautiful women, you were talking a mile a minute, firing questions at me, and after a while you said to me, ‘you don’t talk much, do you?’.

Greg: I had forgotten the two other friends I was with. They were beautiful. Maybe that’s why Leroy gave me the free beer. They were likely given wine, or cocktails.

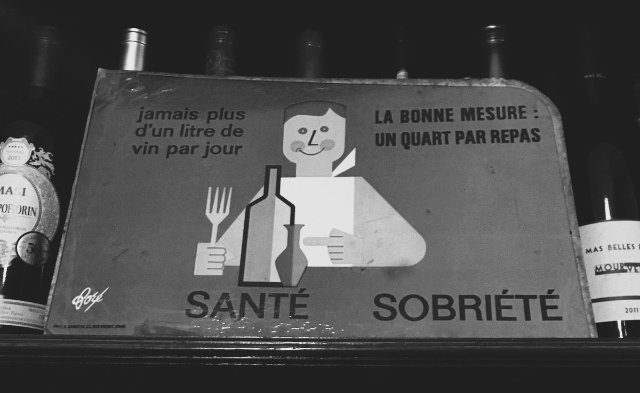

Rafael: In those days a bottle of wine a day was considered good for you, so the French invented the crise de foie, a made-up ailment for a hangover.

Greg: It was even a public health campaign. I had just arrived in Paris, and it immediately caught my attention. Every lamp post, kiosk and Metro billboard had a large poster attached asking Parisians to keep their wine consumption down to one bottle a day. It was an alcoholic-level target but, nevertheless, in Paris very stringent stuff. Then again, there were no posters about cocktail consumption. Or, for that matter, about drugs. Not that I witnessed. Certainly not by the look of some of the locals on the Rue Clauzel.

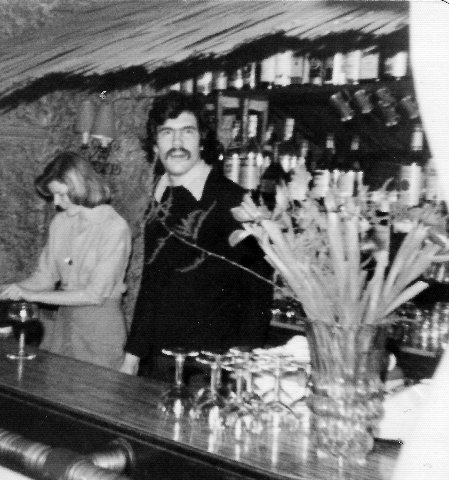

Rafael: Leroy taught me the ropes, how to spot the junkies by their eyes. He once told me about Billie Holiday missing her heroin connection in the early fifties. He fed her yoghurt to get her through the night until her connection showed up in the early morning.

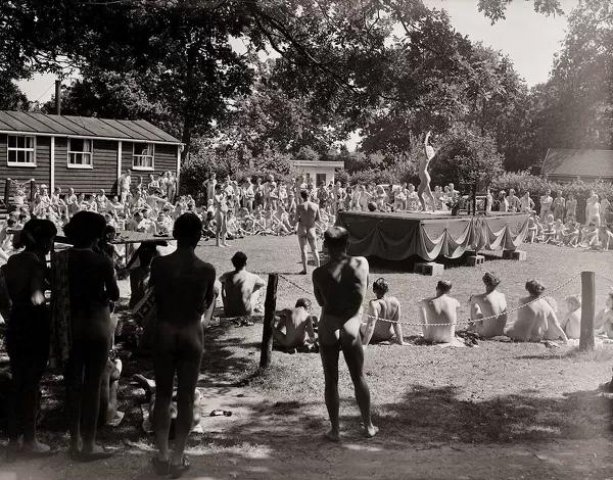

Among the other clients Leroy pointed out were the high-class prostitutes, at five thousand francs a night, most were bilingual or trilingual, elegantly dressed in exquisite clothes, Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, Givenchy. Truth be told, I could never tell them apart, the wealthy bourgeoises and the expensive prostitutes. The guys they came in with were rarely as elegant. They were wealthy, rich, extrovert, often rude and crude, but the manageress put them in their place. Leroy also taught me to spot the heavies, the real estate goons up from Nice and the Côte d’Azur; these guys swaggered in and asked for Monsieur Leroy, and after a couple of times, Leroy told me they came to try to make him sell a large piece of land he owned near Nice. He had bought the property when he won the Irish Sweepstakes back in the fifties, and by now the land was worth millions. Leroy had turned his land into a nudist colony, and he liked to go down there in the summer and walk around buck naked.

Greg: Sometimes he walked around the restaurant buck naked. Or close to it. He would come in just wearing one of the large pink tee shirts he was always in. Like he simply forgot to put on the loose trousers he also perpetually wore. It was rare that he wore anything different. I used to wonder if he ever changed his clothes. Then one day I went up the street to his apartment to get a box of spices or something. He had clearly just done his laundry because hanging over two or three clothes lines stretching back and forth across his kitchen, he had hung up six or so identical pairs of freshly cleaned trousers and an equal number of meticulously washed large pink T-shirts.

That pink T-shirt/easy trouser combo may have clashed with the ‘haute couture’ of many of his guests, but it was methodically assembled and worn every day. Except for those few days when the T-shirt came alone. The shirt never hung much lower than his waist so there would follow a short commotion as the manageress quickly ushered him back to the salad making station while one of the waitresses went back to his place to fetch the pair of trousers still waiting on the line.

Rafael: Now, to get back to your work as the dishwasher and my job as the bartender.

Greg: You at your post and I at mine. Until...

Rafael: You came out of the kitchen one evening and noticed that there were many people at the bar. You barged your way through and commented that maybe I should go back to the silence of the dishwashing tub in the kitchen, and you would handle the bartending. You loved to talk, and I didn’t. So that’s what we did off and on. I washed dishes, and you served drinks and chatted up the clients at the bar.

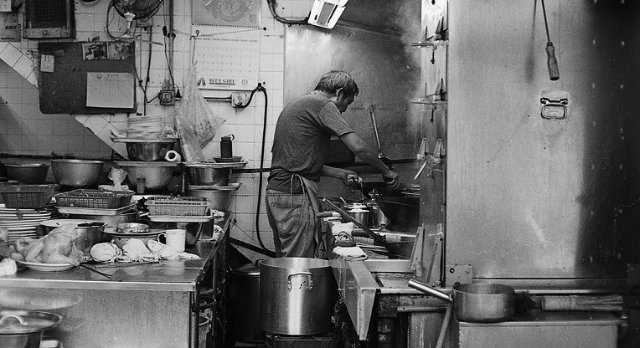

Greg: That is one version of ‘the switch’. I will confess that people, the bar, the general hubbub always looked like a hugely fun party scene from my perspective. And I did like to engage. I don’t remember the incident as me ‘barging’ so much as being permitted a minute breather to take in the fresh air and join the privilege of the bar. I desperately hoped my greasy T-shirt and the sweat still beading on my forehead was not a dead giveaway of my actual role and identity. (I was allowed, officially told, not to wear my wet apron in the dining area.) But that is not when or how ‘the switch’ happened. The origins of the switch happened when you, my friend, descended into my world. You came walking back to the kitchen underworld to use the toilet or looking for angostura bitters. After you had finished doing what you had to do, you looked in the kitchen, saw me alone, my hands, forearms, elbows and way too much of my biceps deep, deep, deep into the brown swill of the sink, and, I guess, you saw heaven. What I do remember is you walking up behind me, leaning forward and whispering in my ear:

You: ‘You are so lucky, Greg.’

Me: ‘What??’

You: ‘You are so lucky, being back here.’

Me: ‘How is that?’

You: ‘By yourself. You don’t have to talk to anyone. You can be alone.’

Me: ‘Are you kidding me?’

You: ‘No. I’d love it.’

Me: ‘Really? If you want to switch, let’s do it.’

So, we did. We talked to the manageress and Don. They thought you were out of your mind. But you were adamant that dishwashing was some kind of utopian existence that you were desperate to conceal yourself within. I think Don could not wait to get you back in the kitchen. He was positively delighted with the idea. Over the moon. And the manageress? Well maybe she had one or two scores to settle. Anyway, the next night we switched. I could not believe my luck. The universe had finally smiled on me.

Rafael: And I was genuinely content communing with the greasy soap suds, listening to Don muttering about everything that was wrong with the world. It was a calming background voice, a human chirping. I wanted the silence of the dishwater. Making salads wasn’t my passion, but it was a little like bricolage. And the only human sounds were from Don, cursing everything, and chuckling and cackling every so often. Saying a hundred times that timing was everything, in the kitchen and in life, and he’d intersperse his culinary philosophy with politics and how ‘Hitler was damn efficient, the man knew what he was doing, getting rid of all that mixed blood’, those were his words. Never for a moment seeing that he was pretty mixed himself, African American and Sicilian. Oh no, that never crossed his mind, at least not in the kitchen. After the racial stuff, Don would eventually get back to the manageress; now there was racial purity, blond and as Nordic as you can get, with a body to beat the band, he’d say.

Greg: So, we were both fully content with the new situation. Fair trade. Good swap. The switch of the century.

Rafael: And there was also Don’s running commentary about the waitresses coming in to pick up the food, how the girls waddled or sashayed or strutted their stuff. Don would cackle, slapping a greasy utensil against his apron. He was a good cook, all the customers agreed on that. I kept my mouth shut. I didn’t want to antagonize the guy.

Greg: So, then, maybe it was not so perfect?

Rafael: For all I knew his temper might explode and he’d grab me by the scruff of my neck and push my head down into the dishwater, and I’d hear ‘is this what it feels like to fuck my blond girl? Huh?’

Greg: Nevertheless, it all went extremely well for a few hours until Leroy came in. I could see he was in a temper of some kind—and not a good one—as he passed by the bar. He gave me a questioning look like something was out of place. Then he entered the kitchen and saw you. He immediately went into an angry rant. I could hear it from the bar. Don and Astrid trying to explain the idea to him. It was only for a night they were saying. He simmered down a fraction, but I could still hear his growl. I assumed it would be mere seconds before I was thrown back into my scullery solitude, or even out on the street. But then Leroy’s mischievous side kicked in. He suddenly saw the humor and the sheer opportunity for drama. You and he making coffees and salads together. You and Don sharing stories. You suffering the depths of the sweat and the swill. Let the switch continue, he declared.

Rafael: I don’t remember much about making salads, just the lettuce leftovers which floated up in the dirty water once the plates had been prewashed. Lettuce will last forever I thought to myself, the other stuff disappeared, the carrots and tomatoes and onions and bits of eggs. The lettuce beat them all, drowned them, and in the water, the leaves took on all kinds of shadings, from dayglo to rust brown. Lettuce must have been around with the dinosaurs. It’s what they, the dinosaurs, ate that made them grow so big.

Greg: I do not know how to read this. Which are you? The onions or the lettuce?

Rafael: Luckily for me, Leroy patrolled the kitchen frequently and kept Don in check.

Greg: Luckily for me, Leroy enjoyed this theatre as much as I did. How many weeks was it before you escaped the sink? Not nearly enough in my books, but the time I had at the bar was glorious. It gave me a taste of what was to come.