Acquisition and Cultural Stewardship

Non-Weestern Art Objects in American Art Museums

By: Noah Kane-Smalls - Oct 28, 2025

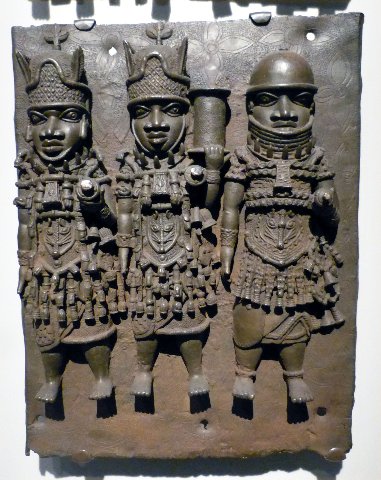

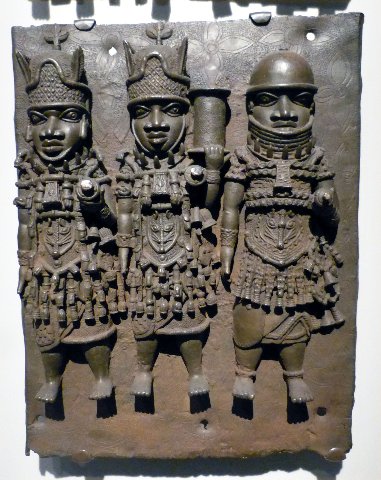

The Eurocentric view of "other" cultures, particularly through the lens of anthropological practices, has long shaped the way non-Western art and cultural objects are perceived and presented in museums. The commodification and recontextualization of sacred, ceremonial, and culturally significant objects as art, particularly by institutions that continue to distance themselves from the ethical complexities of such acquisitions, is an issue that demands incisive attention.

The critical need identified here is for art museums to reconsider their roles in cultural stewardship, particularly when the motivations for acquisitions can be influenced more by market trends than by thoughtful, community-driven curatorial research. Museums, as institutions that preserve, interpret, and display cultural artifacts, have long been shaped by dominant power structures and economic forces, which often prioritize market value over cultural significance or ethical considerations.

In a world where donors, from historically privileged backgrounds, hold significant sway over collection priorities, it’s increasingly difficult to ensure that acquisitions reflect a diverse range of cultures, histories, and perspectives. This problem is compounded by the fact that museum staff are often predominantly white, with limited representation from the communities whose artifacts and narratives they are entrusted to preserve. Without inclusive and equitable representation in staffing, curatorial practices, and decision-making, there is a risk that museums may perpetuate the very systems of exclusion and inequity they seek to avoid.

To address these issues, museums must engage in a deep and ongoing process of self-reflection and reassessment of their missions, practices, and relationships with the communities they serve.

In recent years, art museums have come under increasing scrutiny for their role in the acquisition, display, and interpretation of objects from cultures that have been historically marginalized or misrepresented. The practice of collecting cultural artifacts through a Eurocentric lens is now widely regarded as outdated and ethically problematic. Often, objects that are interpreted as "art" are viewed without regard to their sacred or ceremonial significance, reflecting a deep ignorance of their original context.

At the same time, concerns about provenance, historically exploitative collecting practices, and monolithic curatorial perspectives are being challenged. While the field of anthropology increasingly rejects these objects as unethical holdings, the field of art history has often absorbed them into the canon of European art. This shift allows academic institutions to preserve the value of these objects as commodities, while maintaining "ownership" through their transfer between departments.

Had this approach not been developed by academic collections, these institutions would risk losing not only the fiduciary value of these objects, but also their role as custodians of cultural heritage. Additionally, they could face growing scrutiny of their collecting practices, potentially losing access to these objects for teaching and public display due to increasing social and ethical pressures.

The Commodification of Cultural Objects

Objects that were once valued within their own cultural contexts for ceremonial, religious, or social purposes are often repackaged within the museum setting to conform to Westernized notions of art. This trend became particularly pronounced in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when colonial-era museums and anthropological institutions collected cultural materials not as integral to the living practices and traditions of their communities but as artifacts that could be analyzed and consumed as commodities. These objects, often produced by Indigenous peoples or colonized cultures, were stripped of their sacred meaning and reduced to mere specimens for study and display.

Today, some art museums continue to accept these materials, sometimes under the guise of “re-contextualization” or as part of a broader narrative on the evolution of visual culture. However, the underlying problem remains: The notion that these objects, previously valued for their ritual, social, or religious functions, can be redefined and re-framed as "art" for Western consumption.

The Role of the Anthropological Museum

Historically, cultural objects were acquired and housed by anthropological museums, which sought to categorize and exhibit them as representations of “otherness.” However, many of these institutions, recognizing the ethical complexities and cultural sensitivities surrounding the display of such materials, have ceased to collect and display them. This shift reflects an awareness of the harmful legacies of colonialism and an acknowledgment of the need for greater respect and cultural understanding.

In contrast, some art museums continue to acquire such objects under the assumption that they now fit within the broad definition of "art"—or at least that they can be framed in a way that emphasizes their aesthetic or formal qualities. This process often involves applying a contemporary artist's perspective to "validate" these objects as art, thus maintaining their status and value within the art market. This practice not only fails to honor the cultural significance of the objects but also continues to perpetuate a cycle of commodification.

Unsolicited Gifts and Donor Influence

An additional layer to this challenge is the influence of certain donors or collectors who seek to purge their own collections of ethically questionable or culturally contentious holdings by donating them to art museums. These unsolicited gifts—often in the form of cultural objects—are sometimes presented to art museums under the premise that they will be valued for their aesthetic qualities, rather than their cultural or historical context. The fact that these objects were once used in sacred ceremonies or were considered integral to a culture's way of life is often overlooked in favor of their perceived value in the art market.

This can create a troubling dynamic in which museums act as intermediaries for the commodification and decontextualization of cultural materials. Rather than critically examining the source and intent behind these acquisitions, museums may accept these objects as donations without fully considering the cultural implications, ethical responsibilities, and potential harm that could arise from displaying them in an art context.

Moving Toward Ethical Stewardship and Cultural Collaboration

To address these issues, art museums must move away from outdated models that continue to reframe cultural materials through a Eurocentric, anthropological lens. Instead, museums should strive to be more transparent and collaborative in their approach to cultural materials from Indigenous and non-Western communities.

- Collaboration with Cultural Communities

Museums should actively seek partnerships with the communities from which these objects originate, respecting their sovereignty over cultural heritage and ensuring that their voices are included in the narrative. This can involve consultation, joint stewardship, and collaboration in the interpretation and display of these objects. Indigenous and non-Western artists, curators, and cultural practitioners should be at the forefront of shaping how their cultural heritage is presented in museums.

- Recontextualization and Repatriation

Rather than viewing cultural objects as merely aesthetic or collectible, museums must adopt a more nuanced understanding of their significance, emphasizing their role in living traditions. Efforts at repatriation and restitution—returning objects to the communities of origin—must be prioritized, as these objects are often deeply intertwined with cultural identity, history, and spiritual practices.

- Critical Reflection on Acquisitions

Art museums need to be more discerning when accepting objects from donors, particularly when the provenance or cultural context is murky. Museums should establish clearer ethical guidelines for acquisitions and focus on collecting contemporary works that speak to the diverse, evolving experiences of different cultures, rather than collecting cultural materials that have been divorced from their original contexts.

- Decentering Eurocentric Narratives

Museums should make a conscious effort to decenter Eurocentric perspectives in exhibitions and collections, moving toward more inclusive, pluralistic narratives that recognize the complexity and richness of global art traditions. The interpretation of "art" should reflect the diverse cultural frameworks from which objects arise, not just the dominant Western art canon.

Conclusion

The ongoing practice of commodifying and recontextualizing cultural objects as "art" continues to perpetuate outdated and ethically questionable paradigms. Art museums have a responsibility to critically engage with the complex legacies of colonialism and the misrepresentation of cultures, and they must take steps toward more respectful and informed practices in their acquisitions and exhibitions. By acknowledging the sacred, ceremonial, and culturally specific meanings of these objects, museums can move toward a more inclusive, ethically grounded approach to cultural stewardship that respects the dignity and heritage of all cultures. This shift requires a reevaluation of what it means to collect, display, and interpret art in the context of an increasingly globalized and interconnected world.