Bringing King Kong to Broadway

Developing the 20' and 2000 Pound Gorilla in the Room

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 06, 2018

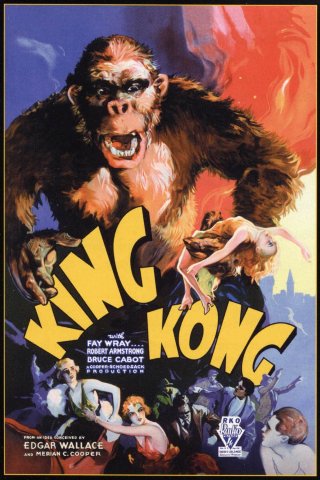

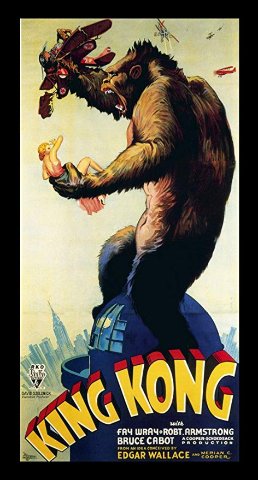

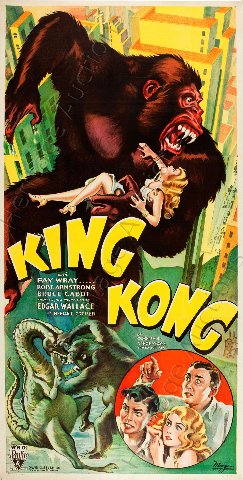

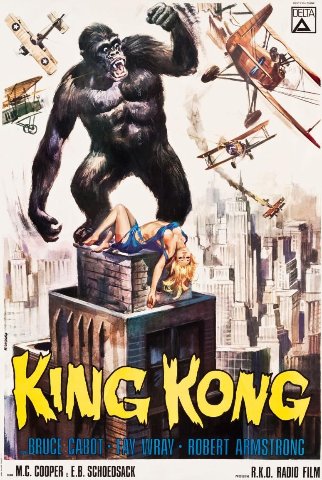

In 1933, a mega great ape, clutching a terrified but smitten Fay Wray as Ann Darrow, scaled the Empire State Building, then the world’s tallest building. The camp/ classic film King Kong has endured in hearts and minds. There were full scale Hollywood remakes in 1976 and 2005 as well as numerous spinoffs in every form of graphics, fine arts and media.

Arguably, the most ambitious iteration of the iconic legend of horror, love, exploitation and bestiality is taking Broadway by storm for what is anticipated as a long run at New York’s generously scaled The Broadway Theater.

It’s been a long and winding road since 2010 for the Australian husband and wife team of producer, Carmen Pavlovic, and scenic and production designer, Peter England. They mounted a version of the musical in Melbourne in 2013. They hoped to transfer to Broadway by 2014 but it has been a labor of love since then.

Carmen Pavlovic is the chief executive of the animatronics company, Global Creatures, best known for arena shows like “Walking With Dinosaurs.” They are co-producing King Kong with Roy Furman, a Broadway veteran.

During the New York Conference of American Theatre Critics Association there was a session, moderated by Jim Farmer, “From Page to Stage: The Journey of the New Musical, King Kong. ”

There was a similarly themed session last year for “The Band’s Visit.” We all know how that turned out. During the coming awards season the odds are that “King Kong” will earn buckets of trophies primarily for its daunting, jaw dropping, technical accomplishments.

ATCA members saw the show during its last week of previews. We were, however, told by the director, Drew McOnie, that the production was officially “frozen” on the evening before the panel. He was still providing notes and continuing to tweak the human aspects of the musical.

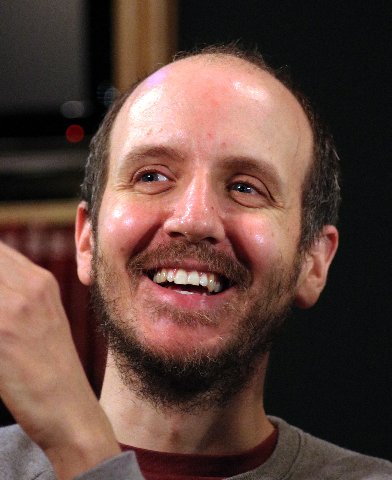

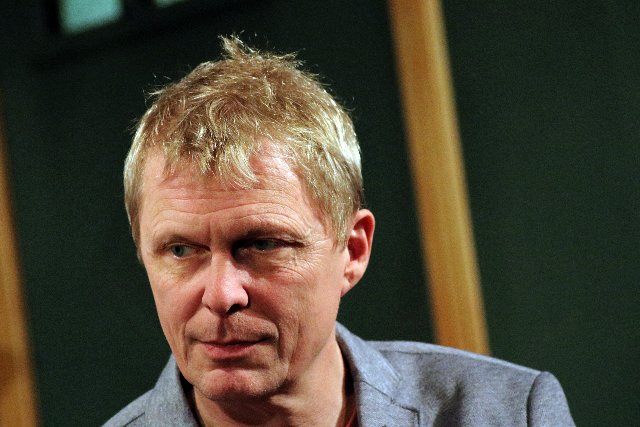

Joining the lively and informative discussion were book writer, Jack Thorne, and composer Marius de Vries.

As the dialogue unfolded, confirmed by what we saw on stage, this complex and wildly creative/ ambitious production was at the very least double trouble. Most formidable was the technical challenge of creating what proved to be an amazingly life-like, richly nuanced, 20’ and 2000 pound puppet.

The other part of the creative dichotomy entailed creating a plausible and relevant update of a story that we all assume to know. There are cast in stone aspects that had to be honored in creating an authentic, palpable, reenergized King Kong.

Those elements ranged from the scream that enshrined Fay Wray in the cinematic hall of fame. Then, how to depict having the gorilla scale the Empire State Building and endure getting gunned down by a swarm of vintage biplanes?

As the writer Thorne explained much of what we experience is about what this King Kong is not. Jack, the love interest of Ann, is gone. She doesn’t scream. In fact she engages in a deconstruction of why being asked to scream is so, like, demeaning. This a post modern, Me Too, leading lady.

An ATCA member asked how the racism of natives of Skull Island would be negotiated? There was a surprisingly simple solution. Thorne told us that the island is uninhabited but for spirits that are vividly depicted.

Much of the delay and expense of this production centered on developing the enormous puppet. It is so complex and expensive that it evoked a range of questions. Thinking of the downfall of Spider Man we were relieved to learn that no actors have been rushed to the emergency room. The leading lady Christiani Pitts gamely is handled by Kong and even climbs up on his back while in motion. That aptly falls under the show biz adage of working without a net.

Combining the puppet with an avalanche of special effects it is speculated that Kong cost a multiple of his weight in gold. Pavlovic fudged on quoting a precise bottom line. Suffice it to say that it came in at about or more than very expensive new productions like Frozen and Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. The average new Broadway musical costs in the range of $20 million.

In the most recent tally King Kong, in previews, took in $674,934 of a potential $1,166,006 or 57.9%. The average ticket cost $62.85 and top price was $258. Some 9,906 seats were sold from a capacity of 10,428. Those numbers put King Kong in the mid range of current shows. For comparison consider Hamilton, $2,054,953, and the relatively new shows Frozen, $1,299,259 and Potter, $2,054,952. There are of course too many variables to make direct comparisons.

Staggering production costs figured into another panel that explored “Taking a Broadway Show on the Road: Tour Producers Discuss the Trade.” The more lavish the Broadway show the more difficult and expensive to break it down. Add to that a map of short runs on the road. Imagine loading in and out a schedule of essentially long weekends. It takes a year or two of planning.

Assuming that it’s a hit on Broadway will there be a road company of King Kong? While still facing opening night reviews Pavlovic is planning ahead. There are issues of finding large enough regional venues. Add to that a complex ballet of choreographing around other touring shows. The producers who do this work told us that there is an ongoing professional synergy that makes it happen.

In developing the puppet a challenge has been to make it relatively light weight and flexible enough to convey a range of convincing and evocative anthropomorphic movements and emotions. The puppet is manipulated by a team of ten, ninja-like road warriors. They are seen by the audience but in a manner that does not distract.

Given the staggering costs to develop for Broadway what are the odds and time frame of recouping that investment? As Pavlovic explained the bonanza of Hamilton changed the algorithm. We are in the age of priority seating for hit shows. When Lin Manuel Miranda returned for a one night benefit of Hamilton box office price for best seats topped $1,000.

Currently the average Hamilton seat costs $263.15 topping out at $849. Essentially a solo show, with minimum operating expenses, Bruce Springsteen commands similar scheckels with an average ticket at $511.58 and $850, a dollar more than Hamilton, for the best seats. For that money, presumably, Bruce autographs your Playbill.

Running the numbers, based on 75% occupancy, Pavlovic speculated that King Kong may reach its nut in twelve to eighteen months. As the most spectacular new musical of the season there are legs to make that happen sooner rather than later.

That’s a scenario that would make a contemporary Max Bialystock go absolutely bonkers.

What follows is a cheat sheet for the technical specs of King Kong.

Broadway’s King King brings together the worlds of animatronics and puppetry to provide scale and spectacle with a subtlety of expression that has never been seen on stage. Kong hits the stage 85 years since the original Merian C. Cooper movie premiered.

- King Kong is part marionette and part animatronic puppet, made entirely in Creature Technology Company’s Melbourne workshop where the creatures from Walking With Dinosaursand How To Train Your Dragon were also made.

- Kong is a 20ft tall, 2000 pound puppet – although this sounds heavy the design approach was to make Kong as light as possible in order for him to be as dynamic as possible on stage.

- A series of articulated welded steel space frames provide the skeleton of Kong. Fibreglass forms give the body shape and carbon fibre shells make up a light weight skull and jaw.

- Inflatable air bags are patterned into forms for his chest and abdomen making Kong not only lighter than he appears but also very flexible.

- His legs and arms are built on a series of high pressure inflatable tubes which provide resilient, lightweight, performer friendly structures. Their compliant nature (compared to rigid options such as steel) allow his limbs to perform dynamically without destroying the stage or set.

- Kong’s surface is made up of a series of sculpted flexible muscle forms. They stretch and change shape as Kong moves his joints – Kong is essentially a moving sculpture.

- Inside Kong there are 985 feet of electrical cable, 1500 connections and 16 microprocessors. Kong even has his own on-board hydraulic power with a quiet liquid cooled pump.

- Suspended from a giant gantry crane in the ceiling, his body is moved around stage from disk structure above him housing a series of motors and winches.

- Kong has over 45 driven axis of movement - from the small servos that move his facial expression, pneumatic air muscles that control his wrists to powerful hydraulic cylinders that pivot his hips, move his shoulders and drive his neck.

- All of these driven axis are controlled remotely by a team of 3 Voodoo puppeteers from a soundproof booth towards the back of the auditorium. They control the Voodoo Rigs – custom designed remote control devices that send input signals to a custom computer control system designed specifically to control animatronic puppets.

- One of the Voodoo puppeteers also drives the voice of Kong which is digitally manipulated live to provide the dynamic range of Kong’s expressive sounds.

- The detail of Kong's facial expression is delivered by 15 industrial servo motors (the same ones used in the NASA Mars rovers). Kong's eyebrows, eye lids, nose, lips, mouth corners and jaw are shaped into pre-programmed expressions which are then engaged and mixed live by the puppeteer providing a virtually infinite number of possible expressions for Kong. The result gives Kong a subtlety of expression normally reserved for high-end film computer graphic creatures, and never seen on stage before.

- The King’s Company (10 very fit dancers and physical performers) provide all the manual performance of the puppet. Using ropes, hand holds and their own inertia they control the limbs of Kong.

- Seen on stage the Kings Company contribute to the energy of Kong as they pull ropes, grab hold of feet and hands or launch from his back using their weight to thrust his fists into the air.

- There have been two full-sized Kong prototypes before the final ‘sculptural-look’ Kong appearing at the Broadway Theatre.