Sol LeWitt Wall Drawing Retrospective at Mass MoCA

Art World Gathers in North Adams for Weekend of Celebrations

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 17, 2008

On every level it was a brilliant triumph as Mass MoCA launched a new, 30,000 square foot building which, on three floors, houses "Sol Lewitt: A Wall Drawing Retrospective." In a strategy that is possible only because of the vast undeveloped real estate of the sprawling, 17 acre, former Sprague Electric Company campus, the special exhibition will remain on view for the next 25 years.

The Sol LeWitt installation becomes a virtual museum within a museum. It is anticipated that this will represent an attraction which will lure tourism to the region and improve its downtrodden economy. It is the much needed shot in the arm that Mass MoCA and its supporters have been hoping for.

During the ribbon cutting on Sunday capping a weekend of special events, Mayor John Barrett, of North Adams, commented "Twenty years ago, who would have thought we would be standing here today." Behind him and LeWitt's widow, Carol, who shared the podium, rose the wing of the museum which has just come on line. "If you predicted then what is here today you might have been smoking some funny stuff."

The semi-permanent installation represents a collaboration between Carol LeWitt, the family and estate of the artist, who was born in 1928 passed away in 2007, Yale University Art Museum, which owns the rights to many of the wall drawings, Williams College, as a partner in the project, the Clark Art Institute, a neighbor and friend, as well as, the vision and energy of Joe Thompson, the director of Mass MoCA.

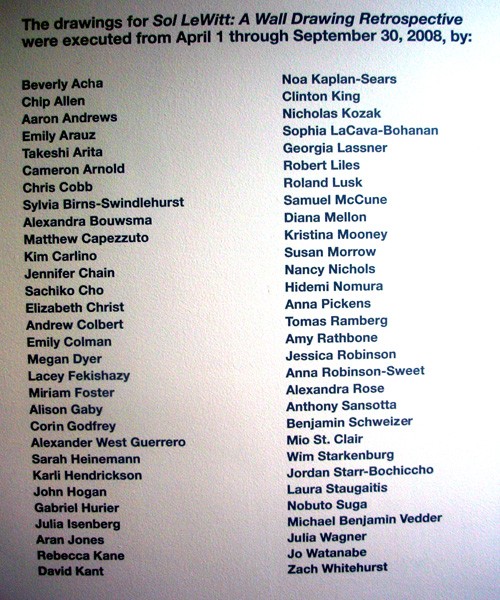

Before he died, LeWitt toured the former industrial space with Thompson and discussed the possibility of an installation. When Thompson asked the artist what part of the building interested him, the response was "all of it." Even though he did not survive to see the works installed, he personally selected the placing of the series of pieces. There is a staff of artists who had created his works in various sites and locations around the world. In this case they were the overseers of the project that recruited a crew of more than 50 young artists and students who labored, a precise term, since April to created 105 drawings following plans that spanned from the early 1970s through his last creations.

One enters the new building through the lobby of Mass MoCA. There is a staircase, as well as elevator, that conveys you to the second level. From there you walk down a long, enclosed corridor to the second floor gathering space of the LeWitt exhibition. It was nostalgic to walk through that cat walk once again as I had more than 20 years ago when Tom Krens took me on a tour of the buildings which he was then proposing would one day become the largest contemporary art museum in North America. From this walk way to the second level you encounter LeWitt's work at Mid Career. Below, on the first floor, is the Early Work and on the top floor, the Late Period. It vividly allows an overview of his entire development as a conceptual and minimalist artist.

Like many who live in and around Mass MoCA it is work that I will absorb over time. There is no rush to probe its daunting depth and nuances. It is the kind of work that demands time, study, and patience. It encourages repeated visits as there is far too much to take in during a single visit even of some duration. I expect that it will be revealing its secrets to me for years to come. In another article we will offer first impressions and may come back to update them from time to time.

Yesterday was our first visit. There had been offers to see the work in progress but I preferred to wait for the finished product. It proved to be explosive and intoxicating. The more so as the Veuve Clicquot champagne was poured generously during the member's opening. I like seeing work for the first time during an opening. For me, it is particularly heady and insightful to view art as it bounces and ricochets off people. It is the chance to experience the art with an audience and to share in and feed off of that energy. For a time, when I was a beat movie critic, to my dismay, I found that one attended screenings on week days in a tiny theatre with a dozen other critics. It was a rule that nobody displayed any evidence of response. I thought it was a really crappy way to see a movie. During the gala LeWitt opening, as throngs of art world VIPs milled about and tossed air kisses, the mood was buoyant and exhilarating.

It was also a great day for celebrity spotting. There was a terrific buzz as Chuck Close wheeled about. Or Jenny Holzer breezed through a gallery. Sunday was the last day of her vast installation. There were dozens of museum directors and curators. All of LeWitt's dealers attended including Barbara Krakow and Portia Harcus from Boston. Plus gaggles of rich and famous collectors who slipped by exuding power and privilege. You could smell the money. Or as the artist/ entrepreneur Eric Rudd put it "Aren't you glad now that you moved to North Adams?" With its proximity to such world class arts and culture. At long last the dream that Mayor Barrett discussed is becoming a reality.

The next big opening, hopefully with more vintage champagne, will occur when Michael Conforti, the director of the Clark Art Institute, in neighboring Williamstown, presides over the opening of the Clark's new building on the Mass MoCA campus. There are still more empty buildings and it is widely speculated that eventully they will be developed to house a permanent collection. More like what one sees at Dia Beacon, which was the vision of Krens from the beginning.

It is well known that major museums are able, at any given time, to display only a small increment of their permanent collections. This applies as well to ambitious private collections where much of the work is in storage. The concept of Krens was that museums and collectors would be willing to make long term loans that would fill the vast spaces of the former Sprague Electric. While this concept started with his vision for Mass MoCA Krens expanded on that when as the director of the Guggenheim Museum he initiated several satellite museums.

While Jock Reynolds, the director of the Yale University Art Museum, presides over many of the plans and rights to the wall drawings there was only an increment of space in which to display them. By creating a partnership with Mass MoCA, Yale was able to fulfill its responsibility to the LeWitt estate to display what it owns. In this arrangement everyone appears to benefit.

Friday Night

The weekend long launch of the LeWitt retrospective started on Friday with a reception at the Williams College Museum of Art and its small exhibition "The ABCDs of Sol Lewitt" which presents a selection of the artist's geometric minimalist sculptures. I have always found the sculpture to be less evocative than the more explosive, daring, complex, and colorful (mid period and beyond) wall drawings. WCMA has a special affinity for LeWitt as he assisted its students to install one of his drawings around the free standing staircase of the Charles Moore designed expansion of the museum.

During the WCMA opening we were riveted by the total gonzo installation of more than 100 square format, silver gelatin prints "Zu Zheng: The Chinese." The artist credits Diane Arbus and August Sander as inspirations. Some of the images were grim including individuals with amputations and horrific tumors as well as lots of corpses, actors, and drag queens.

Lisa Corrin, the director of WCMA, spoke about the Williams collaboration with Mass MoCA and described that LeWitt retrospective as "Our newest and largest Williams classroom." Williams College president, Morton Oliver Shapiro, described first learning of the project on "Joe's (Thompson) porch. He showed me a model of the building where you could take the roof off and see inside. I thought the model was interesting but then he said 'we're going to build this thing.'"

Shapiro commented that Thompson had once been his student but quipped that at the time he had little sense of his later development as a major museum director. This segued into familiar remarks about the "Williams Mafia" of museum directors, curators, and artists. He even "forgave" Jock Reynolds, the director of the Yale University Art Museum, for not having been a Williams grad. After all, Shapiro remarked, "Not everyone can get into Williams." Later, I caught up with Reynolds, whom I had written about for Art New England when he was director of the Addison Gallery of American Art at Andover Academy I asked how he had managed to become a museum director without a Williams degree. He laughed and explained that "After Andover I went on to the University of California and never expected that I would end up in the museum world."

Saturday Morning

On Saturday morning, at 10 AM, there was a strong turnout at the '62 Center for Dance and Theatre of Williams for a lecture and discussion. Lisa Corrin introduced Andrea Miller-Keller, the former curator of contemporary art for the Wadsworth Athenaeum. She ran its legendary Matrix program for emerging artists and Corrin discussed her more than 185 special exhibitions. Miller-Keller was a close friend of the artist and is one the foremost scholars of his work.

The 90 minute illustrated lecture by Miller-Keller provided a warm and insightful introduction to the work. She noted that the audience was filled with individuals who knew the work well and that, for them, it would be a review of highlights. She very briefly provided a few biographical facts but stated that "Sol always wanted you to focus on the work. There are only a couple of published photographs of him."

Her presentation was clear and insightful. One could not have asked for a better introduction and it prepared you to see the installation and what to look for. The night before President Shapiro had used the term "genius" to describe LeWitt. While Keller-Miller, never evoked such superlatives, but through a careful construction of the visual evidence, led us to that inevitable conclusion. Mostly, she provided documentation of his courage, modesty, and inventiveness. She argued that LeWitt, like others of his generation, were caught up in the end game of the death of painting particularly after the Triumph of American Art (the Irving Sandler term) and the excesses of Abstract Expressionism. LeWitt appeared determined to deny the elements of romance and expression in his methodical, abstract, non objective, conceptual approach. He invented a series of rules and paradigms that evolved into mark making; initially lines drawn on walls according to sets of rules.

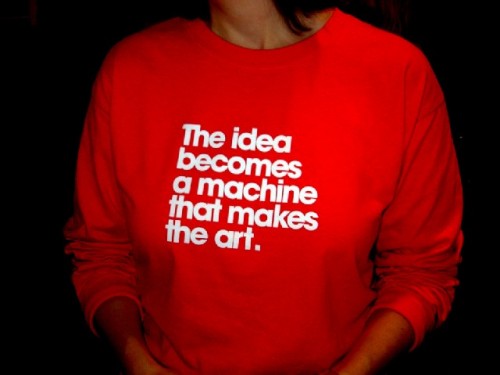

LeWitt was a paradigm of his generation of artists who through Cartesian logic wanted to strip down and reinvent the philosophical and theoretical basis of art. The initial phase was so reductive and generic that it was dubbed Minimalism. Like others LeWitt derived systems and strategies, taking on the approach of Marcel Duchamp and his conclusion that painting was "too retinal." This method was initially called "Systemic" and eventually was better known as "Conceptual Art." In LeWitt's radical schematics the work of art may in fact be executed by others following his elaborate instructions. But, as was typical of his generation, however austere and reductive, it was to be created by the human hand and touch. A point about which LeWitt had a career long struggle as there is a lot of touch and sensitivity to surface, even though executed by others, particularly in the later work. At his core LeWitt saw himself as a vegan artist although viewers will find many of its later aspects quite meaty.

One of the most innovative of LeWitt's ideas is that the work was installed for a limited time and then erased or painted over. It was extreme in not creating permanent objects that were readily bought and sold. There was little or no material value attached to the work. Again, like the Italian Arte Povere artists, the Minimalists embraced generic industrial materials and methods. There was an anti materialist, revolutionary spirit reflected in the vast Earth Works of artists creating non museum scaled installations often in remote locations. This approach resulted in art destinations and, arguably, Mass MoCA, with its non traditional, industrial spaces, is one of them. LeWitt came of age during a generation of student protest and social change and must be seen in that context.

Initially LeWitt visited the homes of collectors and was inspired by the setting to create a work as a set of diagrams and instructions. If a work was later sold or donated to a museum it had to be destroyed in order to be recreated. So there was an avant-garde, anti materialist aspect to his creations. As time evolved the sets of rules became ever more complex and, eventually, colorful and even Baroque. During questions following the presentations it was asked what relationship LeWitt's colorful and decorative later works had to Op artists such as the once popular Victor Vasareley?

Although LeWitt, according to Miller-Keller, did not seek fame and fortune, it came to him by default. When he had means and resources he bought the work of other artist friends. He was generous in donating work and support to museums. One sensed that he was a remarkable human being who protected his private life. This encourages a formalist dialogue about the work but when confronted by the immensity, power and range of the Mass MoCA installation one cannot avoid coming away with a strong sense of the man. His persona emerges despite his apparent desire to suppress it in favor of the higher purpose and purity of the work itself.

Following Miller-Keller were brief remarks by the artists, Michael Glier and Mel Bochner, as well as, the scholar/ curator, Chrissie Iles. The remarks of Bochner were particularly warm and insightful. They worked together and shared many ideas. He talked about the impact of the 1968 Met exhibition "The Great Age of Fresco: Giotto to Pontormo." As young artists, who had not yet traveled to Italy, they were absorbed by the works particularly examples when restorers had removed layers of plaster to reveal the sinopias or underpaintings. They were particularly struck by the geometry of Piero della Francesca. LeWitt made drawings that broke down and analyzed Piero's compositions. One sinopia from that exhibition that Bockhner projected and discussed entailed perspective drawings beneath the figurative composition. That encouraged them to make works directly onto walls as well as to refine their work to its basis in geometry.

The presentation by Iles discussed how he photographed a cube from nine possible light directions. These were then incorporated into the wall drawings with illusions of solid geometry. In later work LeWitt dealt with isometric schemes and experimented with illusions of depth while remaining true to the flatness and integrity of the wall as a picture plane. Glier in a personal and poetic manner discussed the primal instinct of destroying the purity of a wall. He compared this to a child dipping into pea soup and smearing it with glee on a wall.

Minimal art can be rather dry and enervating. For most viewers it is an acquired taste. It is a familiar argument that we come to art looking for ourselves. When it is missing the work is viewed as cold and remote. We saw that last summer, for example, when, at Tanglewood, the music of Elliot Carter, which is driven by conceptual notions, was harshly dismissed by critics who should know better. Perhaps we have evolved further in the visual arts having been schooled by the non objective work of modernists from Malevich and Mondrian, through Albers, Reinhardt, Newman and Ryman. Reductive, abstract art belongs to the classical, Apollonian traditions of art. LeWitt's work conveys the notion of "ars gratia artis."

In projects involving many artists working under a master art historians like to identify the individual hand, touch, style, and personality in the workshop of Phidias, Raphael, or Rubens. It is possible that a school of LeWitt will emerge from the many young artists who, literally, had a hand in the work. During the session at the '62 Center, all of the artists who had worked on the LeWitt project were asked to stand. It was amazing to see them. Just before you walk down the catwalk to the LeWitt building there is a wall that lists the names of all those who worked for many months to create the wall drawings. While intense and demanding it was surely a labor of love.

Saturday

This was an occasion to enjoy and celebrate all of that hard work.

Sunday

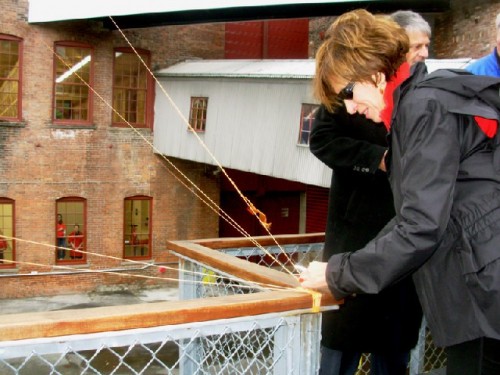

On Sunday the museum was free for the general public. We arrived just before noon for the "ribbon cutting" ceremony. It was set up outside and like many I was not dressed for the occasion as it was a cold and raw day. Lisa Corrin, however, was properly bundled up.

In an interesting LeWitt touch, instead of the traditional ribbon, there were several colored strings attached to the railing of the outdoor café to different points on the LeWitt building. It was an amusing reference to one his works which was to "connect all the architectural details in a room." It is one of the most provocative and engaging of the wall drawings.

There were remarks by Thompson, Reynolds, Corrin and Mayor Barrett. He insisted that Carol LeWitt join him on stage. She was gracious, but like Sol, seemed uncomfortable in the spotlight. She prefers to focus on his work Her generosity and commitment played an enormous role in making this project happen. Turning to Mrs. Lewiit, and gesturing to the building behind him, Barrett commented "It's Sol's work in there but your fingerprints are all over it."

Following the ceremony I needed a hot cup of coffee at Lickety Split. I also enjoyed the opportunity to read the Sunday New York Times provided by the café. After such an intense and busy weekend I was taking a break. To my surprise I looked up to see Mayor Barrett, a cup of coffee in his hand, standing over me. His remarks were addressed to a critic and skeptic. There was the notion of "See I told you so." But we agreed that there is a lot yet to be done in the long slow revival of North Adams. It rapidly evolved into more than a casual conversation.

"I would like to come and talk with you about this" I said. His response was "I'll talk to anyone. Call my office." Ok, your Honor, let's do that. One of the points for discussion and debate is what impact this expansion of Mass MoCA will have on Main Street, area hotels (like the challenged downtown Holiday Inn which is going through transition and change) and restaurants holding on during a tough economy.

This summer Mayor Barrett and MCLA initiated the Downstreet project with several temporary galleries in empty stores. That had closed at the end of October (Jarvis Rockwell's "Maya III" will remain open through January). At the insistence of MCLA and the Mayor the North Adams Cooperative Gallery reopened for the LeWitt weekend. The intent was to show activity on moribund Main Street.

By the time I left Mass MoCA, around 2 pm, the parking lot was full. But there was plenty of parking on Main Street. When I dropped in on the Coop, its director, Diane Sullivan, reported that traffic that weekend has been slow but they made a few sales. During the time I hung out a few people dropped in but nothing like what had been anticipated. It was cold and damp and on Saturday there had been rain. But Sullivan commented that during the summer Downstreet did indeed lure visitors. "They came in wearing their Mass MoCA stickers and we made sales." Later that afternoon there was a closing party during which Sullivan, with warmth and emotion, thanked all those who helped with the Coop and Downstreet project.

What happens next year remains to be seen. While Downstreet focused on downtown North Adams its marketing strategy and outreach did not effectively include the Eclipse Mill with its owner's gallery and the pottery studio of Gail and Phil Sellers, the book shop of Grover Askins, and the gallery of Ralph Brill, or the nearby Kolok Gallery. There needs to be a better plan that connects all of the dots beyond the annual Open Studios. Yes, overall, the traffic and spillover of tourism was better this past summer. Downstreet was a player in that. It was a start but we have to work harder and make it better. There needs to be a cohesive plan for the entire mix of arts and business in Northern Berkshire County. The LeWitt project is a huge step in the right direction but now we need to make it work for all of us.