Shadow Visionaries: French Artists Against the Current, 1840–70

At the Clark Art Institute

By: Clark - Nov 17, 2025

Shadow Visionaries: French Artists Against the Current, 1840–70 opens December 20, 2025

The Clark Art Institute presents an exhibition on mid-nineteenth-century French artists who looked beyond realistic subject matter. Their work encompasses the Gothic nostalgia of architectural photography, the social critique embedded in searing allegorical illustrations, and the literary connections with fantastical art. Shadow Visionaries: French Artists Against the Current, 1840–70 is on view December 20, 2025 through March 8, 2026 in the Clark Center lower level.

Although Realism is often seen as the dominant aesthetic of mid-nineteenth-century France, many artists working outside of painting embraced imagination, dreams, and allegory instead. Working against the grain, figures such as Victor Hugo (1802–1885), Charles Meryon (1821–1868), and Rodolphe Bresdin (1822–1885)—and a roster of early photographers—offered an alternate vision anchored in memory, fantasy, and longing. These “shadow visionaries” recognized the potential of prints and photographs to construct a spiritual consciousness in the art of mid-1800s France.

“This exhibition gives us a wonderful opportunity to explore some of the treasures in our works on paper collection, along with a wide group of special loans from key French and American museums, through a fascinating lens,” said Olivier Meslay, Hardymon Director of the Clark. “The style and subject matter of the works included in the exhibition explore the strange and the surreal, but above all, they provide a rare opportunity to appreciate the singular beauty of the work these artists were producing.”

The exhibition features some 95 prints, drawings, and photographs drawn from the Clark’s collection along with important loans from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Art Institute of Chicago; the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Yale University Art Gallery, and Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris among others.

“Realism has been a stubborn watchword for French art of the mid-1800s, so it is fascinating and surprising to examine a group of artists from that moment who embraced a radically different style. Despite (or maybe because of) feeling out of sync with their times, these artists found beautiful and original modes of expression, using printmaking and photography to represent interior visions rather than visible reality,” said exhibition curator Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

The mid-1800s in France was a tumultuous era that witnessed dramatic political, social, and cultural change. The impact of those transformations on art of the period has often been measured by the painting and sculpture shown at government-sponsored Salons, Universal Expositions, and other prominent exhibition venues, which tended to uphold official narratives of progress. Yet a focus on more private media, such as printmaking and photography, tells a different story. In fact, many artists felt at odds with their era’s celebration of material advancement and modernization. Rejecting the prevailing current, such figures—described as “Shadow Visionaries” for this exhibition—chose dark subject matter oriented toward the irrational, spiritual and fantastical. They used the distinctive characteristics of black-and-white media to convey intense emotions, while producing works of unsparing directness and rare beauty. Although some of the Shadow Visionaries evoked a sense of nostalgia, others dreamed boldly toward an alternate future, anticipating later art movements such as Symbolism and Surrealism.

VISIONARIES IN THE SHADOWS

Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746–1828) was a major touchstone for French printmakers exploring dark, supernatural subject matter. His set of eighty Caprichos (1799) offered a raw modern vision of humankind existing in a state of disquiet, bewildered by an unfathomable universe. Goya’s use of aquatint, a tonal method, in combination with etching revolutionized printmaking and left an enduring legacy. Taking cues from art as well as literature, French Romantic printmakers such as Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) made works that hinted at the mysterious forces beyond the visible. French writer and artist Victor Hugo (1802–1885) observed in the 1820s that “in things there are more than things,” and that “it’s only when the physical world has completely disappeared from [one’s] eyes that the ideal world can be manifested.” This emphasis on the partial, contingent nature of visible reality would profoundly influence the Shadow Visionaries of the mid-century.

MEDIA CLAIMS AT MID-CENTURY

The invention of photography in 1839 shifted the purposes and perceptions of older media, especially printmaking. Photography did not enjoy fine-art status in its first decades but won praise for its objectivity and accuracy of detail. Consequently, printmaking’s ability to reproduce other art forms—and to precisely depict reality itself—came into question. Early commentators on photography emphasized its mechanical qualities over its affective side. In response, etchers began to double down on their own medium’s authentic and personal qualities. Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), for example, likened etched lines to handwriting that left a trace of the artist’s personality on the copperplate. In the 1850s and 1860s, stakes were high for etchers to reclaim their status as creative artists through a focus on original compositions and exquisite printings. In 1862, the publisher Alfred Cadart (1828–1875) and the printer Auguste Delâtre (1822–1907) formed the Société des Aquafortistes (Society of Etchers), which went on to play an outsize role in promoting artistic etching.

HAUNTED NATURE

By the 1850s, the Forest of Fontainebleau was cherished by artists as a space of natural wonder and a refuge from rapidly modernizing Paris, about forty miles away. While Fontainebleau is strongly associated with the Barbizon painters’ elevation of the landscape genre in France, the site also inspired printmakers and photographers to seek new expressive means in their respective media. The Shadow Visionaries did not see nature as an ever-bountiful, all-nurturing force as their Romantic forebears had done. Emphasizing qualities of darkness and shadow, artists such as Gustave Le Gray (1820–1884) and Rodolphe Bresdin (1822–1885) brought a haunting, eerie vision of tangled thickets and gnarled trees rather than verdant prospects and welcoming glades. They knew already that their beloved Forest of Fontainebleau was a sanctuary under imminent threat; day-trippers choked the sylvan paths even as loggers chopped down centuries-old trees. Nature needed protection as much as it offered it.

In Le Gray’s Rising Sandy Path, Fontainebleau (c. 1856), a butterfly-shaped swath of sky sharply contrasts with an area of deep shadow obscuring the left side. This dark band, likely to be perceived as a chance effect or flaw, is perhaps the photograph’s most salient feature. Like Bresdin’s lithograph, The Holy Family at Rest Beside a Stream (1853), Le Gray’s photograph manages to hold shadow and menace in balanced tension with light and safety. The forest path leading sunward promises quick escape from whatever might be lurking in the shadows.

GOTHIC NOSTALGIA

A potent source of national pride, France’s Gothic architecture had nevertheless suffered long periods of neglect, leading to worries about its ultimate upkeep and survival. Mounting concern for the dilapidated state of centuries-old monuments prompted the French government in 1851 to launch a comprehensive program of photographic documentation known as the Missions héliographiques. Five official photographers–Édouard Baldus (1813–1889), Emile Bayard (1837–1891), Gustave Le Gray, Henri Le Secq (1818–1882) and Auguste Mestral (1812–1884)–accepted assignments to record historic structures in regions throughout France. The resulting images, though not published at the time, were intended to marshal support for the repair and restoration of vulnerable edifices. Their unexpected viewpoints staged a direct encounter with the historical past, sometimes tapping into mournful emotions of nostalgia, loss, and grief. The drive to preserve old buildings in France’s provinces coincided with a frenzy of new construction in Paris, where Baron Haussmann oversaw a massive transformation of the urban fabric throughout the 1850s and 1860s.

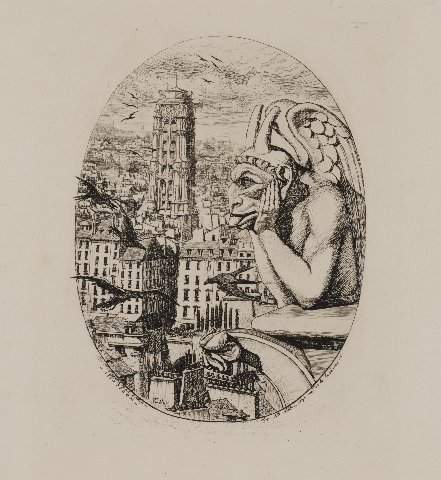

Meryon’s profile view of the gargoyle on the north parapet of Paris’s Notre-Dame cathedral is an icon of Gothic moodiness. Yet, when Meryon made the etching The Vampire (Le Stryge) (1853), the sculpture was brand-new, a modern appendage designed by eminent architect and restorer Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879). Meryon’s Paris etchings attest to his sense of loss as urban transformation swallowed up medieval neighborhoods, like the one where he grew up.

UNDERGROUND

The splendid avenues, boulevards, and shining new façades of Haussmann’s Paris necessitated the destruction of many existing structures—sometimes entire neighborhoods. By one count, 20,000 buildings were torn down for 30,000 new ones erected. Quarries on the edges of the city furnished building materials for dramatic transformation closer to the center. Changes to the urban fabric did not occur just on the surface: creepy belowground sites like catacombs and sewers also figured on the city planners’ agenda for renovation. Printmakers and photographers alike took peculiar inspiration from these hostile, barren, noxious places, perhaps finding in them literal expressions of the “underside” of urban progress. That subterranean locales could be photographed at all was a feat of technology by artificial light that the photographer Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon) (1820–1910) helped to patent. In addition to the ecological costs of thoroughgoing urban upheaval, the digging up of ground layers occasionally unearthed macabre surprises, surfacing as long-buried echoes from the past.

In 1862, Nadar was commissioned by Ernest Lamé-Fleury, a mining engineer and quarry inspector, to photograph the Paris catacombs. Skull-Lined Walls in the Catacombs of Paris (1862) and Catacombs of Paris, "Hallucinations of shadow, light and collodion" Façade no. 3 (1862) are two photographs included in the exhibition. In this macabre underground site, the mortal remains of Parisians across the ages were indiscriminately commingled. Amid so much death, the photographer was intrigued to find a few fish swimming in a small water basin, brought there on a worker’s whim.

The startling image of a cat unearthed during restoration work at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye outside Paris is the subject of Charles Marville (1813–1879)’s The Mummified Cat (c. 1862). The feline was buried in the castle’s foundation around 1547, at a time when burying a live cat in the stones of a new building was considered good luck. It was preserved intact in its airtight surroundings for more than 300 years. Incongruously displayed in Marville’s photograph as the sole organic matter alongside carved stone objects, it appears like a curious totem on a pagan shrine.

HOPE AND DESPAIR FOR SOCIETY

Although a drive for social reform is more typically associated with Realist artists such as Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), the Shadow Visionaries were by no means disconnected from contemporary reality. The main difference was that, rather than depicting the world’s woes in realistic terms, they tended to express them via symbolism or allegory. Identifying as outsiders, these individuals rejected conventional societal norms and made it their business to confront issues like death, pain, and loss with raw, unsparing directness. Certain Shadow Visionaries lived in conditions of extreme penury and material suffering. In addition, several of them suffered mental instability or spiritual crises that, in the most severe cases, led to suicide or the asylum. To the extent they advanced hopes for social change, they voiced these as a critique of the Second Empire’s triumphalist values of industrial progress and material prosperity, pleading instead the causes of pacifism and a morally purifying religious faith.

The lithograph Rue de la Vieille Lanterne (The Suicide of Gérard de Nerval) (1855) by Gustave Doré (1832–1883) commemorates the suicide of his friend, the poet and dreamer Gérard de Nerval (1808–1855). Nerval’s writing often wrestled with the gap between poetic life and reality; he described himself as “wandering between two worlds, one dead [and] the other powerless to be born.” Nerval, after being hospitalized for mental illness, finally succumbed to a crisis of despair and hanged himself on the night of January 25–26, 1855.

Intended as illustrations to a French edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s tales, translated by Charles Baudelaire, the three 1861 etchings The Facts in the Case of Mr. Valdemar, The Pit and the Pendulum, No. 1, and Shadow constitute the high point of Alphonse Legros’s (1837–1911) early printmaking. Legros exploited basic techniques of etching to accentuate the terrifying elements of Poe’s tales. In Shadow, simple parallel lines produce the supersize shadow on the wall and make it blend seamlessly with the candle flames. In The Pit and the Pendulum, the etched lines are most deeply bitten in the lower right, where rats have congregated.

SPACES OF DREAMS

For artists of any era dissatisfied with the status quo, one means of escape has been imagining new or alternative worlds. Victor Hugo spent nearly two decades in exile, but many other Shadow Visionaries pursued dreams of “elsewhere” from inside France, journeying within their minds. Between fall 1853 and summer 1855, while Hugo lived on the island of Jersey, he engaged in regular séances, using the help of a medium to communicate with the spirit world. This impulse to bridge the gap between the realms of the dead and the living connects with the desire, in the burgeoning genre of science fiction, to link known and unknown worlds through supernatural leaps of the imagination. Book illustrations in this genre show how art and literature provided mutual inspiration in the quest to envision otherworldly realms.

As Florian Rodari (Swiss, b. 1949) has written about Hugo’s castle drawings, “These impregnable fortresses . . . are all but indissociable from their equivalents in hollows, caves, underground passages, and dungeons, from which one can escape only by some superhuman feat of will; or they are lairs which shroud the runaway, hero or criminal in darkness.” In Fantastic Castle at Twilight (1853), the fanciful, multitowered castle looks vulnerable in its immensity, wildly illuminated as if—amid a swirling, celestial turbulence that one can only call electrical—lightning has just struck it.

MOVING FROM THE SHADOWS INTO SYMBOLISM

A pupil of Rodolphe Bresdin (1822–1885) and heir to his dark artistic vision, Odilon Redon (1840–1916) worked through visionary themes of human destiny and spiritual questioning in his so-called noirs, or drawings and prints executed entirely in black and white. In the 1880s and 1890s, Redon became a primary standard-bearer of the Symbolist movement. Yet his work also looks back to the example of Goya’s print cycles. In multiple lithographic series, Redon revealed humans perched at the edge of a metaphorical abyss, confronting their deepest doubts and fears. Redon’s prints often include poetic captions evoking the textual sources from which his iconography derives. Apart from those literary cues, the images owe much of their symbolic and expressive power to the balancing of inky darkness with paper’s luminosity.

Redon saved some of his darkest blacks for It is the Devil, plate 2 of The Temptation of Saint Anthony. The lithographic album from 1888 was the first of three Redon would produce in response to Gustave Flaubert’s 1874 novel, The Temptation of Saint Anthony. Massive, frontal, and deeply unsettling, the Devil bearing an armful of deadly sins confronts the viewer as the very incarnation of terror.

Shadow Visionaries: French Artists Against the Current, 1840–70 is organized by the Clark Art Institute and curated by Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

Major funding for Shadow Visionaries is provided by Mireille and Hubert Goldschmidt, with additional support from the IFPDA Foundation and the Troob Family Foundation.

ABOUT THE CATALOGUE

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue, Shadow Visionaries: French Artists Against the Current, 1840–70, with essays by Anne Leonard, Geoffrey Batchen, and Valerie Sueur-Hermel. A look at the imaginative work of artists and photographers who defied the aesthetics of realism in nineteenth-century France, the catalogue is published by the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts and distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut. Though realism is regarded as the dominant aesthetic of nineteenth-century France, an equally fervent movement of dreamlike, allegorical, and eerie literature and art was produced by figures as renowned as Victor Hugo and Odilon Redon. These “shadow visionaries” traversed the boundaries of reality in their work, recognizing the potential for art to construct a spiritual consciousness. Highlighting haunted representations of the natural world, Shadow Visionaries provides an extraordinary look at a popular yet understudied era of French art.

In bringing together a variety of media—from photographs to literature—this catalogue challenges traditional art historical narratives and facilitates ground-breaking dialogues between creative works. Essays by leading curators and historians illuminate the cultural and societal currents that inspired widespread Gothic nostalgia and uncanny constructions of the natural world.

RELATED EVENTS

January 10, 11 am

Manton Research Center auditorium

Exhibition curator Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, introduces Shadow Visionaries: French Artists Against the Current, 1840–70. Offering a new take on mid-nineteenth-century French art, the exhibition emphasizes the powerful role of fantasy and the imagination during an era when Realism was presumed to be ascendant.

Free. For accessibility questions, call 413 458 0524.

SHADOW VISIONARIES FILM SERIES

January 22, January 29, February 5 & February 12, 6 pm

Manton Research Center auditorium

Inspired by the Shadow Visionaries exhibition, the Clark presents a series

of twentieth-century French films that echo with meditations on memory

and longing. Prepare yourself for fantastical allegories and crumbling, ruined cityscapes.

All film screenings are free unless otherwise noted. Accessible seats available.

THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER, WITH NEW LIVE SCORE

January 22

Adapted from Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher, director Jean Epstein conjures an atmospheric masterpiece. The hero, having indirectly caused the death of his beloved, stubbornly tries to resurrect her spirit by devoting himself to painting and sculpture. The screening is accompanied by a newly composed score by Paul de Jong and Matthew Gold, performed live. (Run time: 1 hour, 3 minutes)

Tickets $10 ($8 members, $7 college students, $5 children 17 and under).

January 29

Leprince de Beaumont’s fairy-tale masterpiece—in which the pure love of a beautiful girl melts the heart of a feral but gentle beast—is a landmark of motion picture fantasy, with unforgettably romantic performances by Jean Marais and Josette Day. Director Jean Cocteau’s spectacular visions of enchantment, desire, and death in 1946’s Beauty and the Beast (La Belle et la Bête) have become timeless icons of cinematic wonder.

(Run time: 1 hour, 36 minutes)

February 5

Filmmaker Chris Marker has been challenging moviegoers, philosophers, and himself for years with his complex queries about time, memory, and the rapid advancement of life on this planet. Marker’s La Jetée (1962) is one of the most influential, radical science-fiction films ever made, a tale of time travel told in still images. The nostalgia for architectural photography captured in the Shadow Visionaries exhibition echoes throughout the haunting film. (Run time: 28 minutes)

February 12

In this 1995 film, a child smiles delightedly in his toy-filled room as Santa emerges from the chimney, but joy turns to terror as the bearded visitor is followed by more of the same. Cut to a man screaming in a laboratory where, unable to dream himself, he has stolen the nightmare of a kidnapped orphan. The opening of another of Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s forays into the fantastique is the perfect introduction to an inventive blend of dream, fairytale, and myth. (Run time: 1 hour, 52 minutes)

DINNER AND THE SHOW: SHADOW VISIONARIES

February 14, 5:30 pm

Join Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs Anne Leonard for a special introduction to Shadow Visionaries, followed by a three-course meal inspired by nineteenth-century France. Constellation Culinary’s Chef Chris Gouty brings his creative spin to classical French cooking and the themes of memory, fantasy, and longing that anchor the exhibition. With subtle nods to Valentine’s Day, this Dinner and the Show perfectly combines art history, food, and fun.

The Clark Center galleries will be open from 5:30–6:30 pm with docents stationed throughout. Dinner begins at 6:30 pm.

Tickets $115 ($95 members). A ticket includes three courses and paired wine. Cash bar also available.

EXILED ON THE EARTH: NATURE, TECHNOLOGY, AND RISK

February 21, 2 pm

Richard Taws, professor and head of the History of Art Department at University College London, presents a talk in conjunction with the Shadow Visionaries exhibition. Taws examines how representations of infrastructure, nature, and technology shaped the cultural imaginaries of nineteenth-century urban modernity, and how they intersected with contemporary ideas about time and history in France. Focusing on artists featured in Shadow Visionaries, including Charles Meryon, Victor Hugo, and Nadar, the talk explores tensions between organic life and mechanical form, visibility and invisibility, and tradition and transformation, in Paris and further afield.