Dishwasher Dialogues Pig Alley and Street Theatre

They weren't Wearing Gestapo Uniforms

By: Greg Ligbht and Rafael Mahdavi - Nov 27, 2025

Greg: Pigalle. It always amazed me that Chez Haynes was so close to this pinnacle of the Parisian night. You would never know just by going to the restaurant. Going to work every night, getting off the metro at the St Georges station, and walking the few minutes to the restaurant was a quiet experience. A few blocks from all the lights and traffic and people, Rue Clauzel was a dark, empty street back then. Most likely still is. A very discrete location. I suspect many, if not most of our American clients booked dinner with us followed by a tour of Pigalle. It was a must see on most tourist itineraries.

One night, I remember hearing loud American voices on the street outside the restaurant. A table of three or four had just left the restaurant and now they were outside the front door, upset about something. Suddenly, one of them swept back in through the red curtains and saloon doors and looked up at me and demanded directions to Pigalle, which she pronounced in a sharp New York accent as ‘Pig Alley’. ‘Where is Pig Alley?’ she demanded. ‘I didn’t come all this way to miss Pig Alley.’ She turned to her friends, who had followed her in and were all nodding and saying, ‘Pig Alley’. I gave her directions and off they went. We all laughed about their pronunciation, but in many ways, it was an apt description of the place.

Rafael: What that woman didn’t know was that Pigalle was a famous eighteenth-century sculptor. He did a sitting portrait of Voltaire in his birthday suit. And it seems Voltaire liked it. The statue is in the Louvre. The sex den of Paris named after a sculptor––only in Paris. Pigalle also had the Hermes statue on top of the Bastille column.

Greg: Sex, art, and revolution all rolled into one.

Rafael: Terrific, pourquoi pas? I wonder if Voltaire was a chaud lapin, a hot rabbit.

Greg: A hot rabbit in pig alley. Good juxtaposition of images. What is a hot rabbit?

Rafael: A horny rabbit.

Greg: I shouldn’t have asked.

Rafael: When Chez Haynes closed at two in the morning, the staff would walk up to Le Trafalgar to unwind. The clients and the prostitutes at Le Trafalgar situated off the Rue Blanche, were different from the poules de luxe, expensive prostitutes or escorts who came to Chez Haynes.

Greg: Deluxe chickens, now? This area is beginning to sound more like a farmyard than a seedy red-light district.

Rafael: The place was an unpretentious, old-fashioned brasserie, with a zinc bar, Formica tables and chairs, and tired waiters.

Greg: It was a very cool bar. We were off the beaten track but somehow right in the middle of this amazing slice of Paris nightlife. I am not sure I fully appreciated it at the time. It was just a place we hung out.

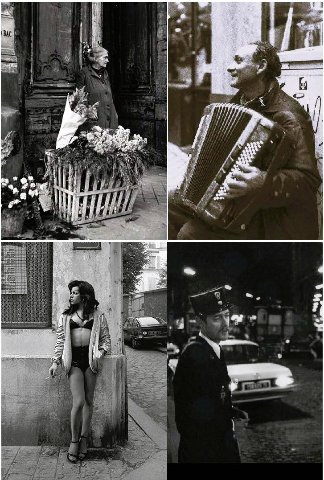

Rafael: Monsieur Xavier, the owner, always greeted us warmly. He had a protruding belly and a curly moustache. The first night we went there he told us he was from Normandy and would always be thankful to the American soldiers who saved France. He had been a young lad then as he watched the Americans after D-Day rumble through the town in their armored vehicles. And some nights when he was a bit soused, he’d puff out his chest and rattle off the famous beaches of Operation Overlord, Juno, Gold, Sword, Omaha, and Utah. The late-night customers at Le Trafalgar were the real fauna of Pigalle-by-night: cops on a break from their beat, flower sellers not selling anything, prostitutes, not selling anything either, musicians resting their feet from their playing in a few bars and restaurants. Most of the year the musicians played outside on the terraces, and now as fall moved into winter it would soon be too cold to play in the street, and most restaurants didn’t want the musicians playing inside. The accordéonistes, guitar and violin players would leave Paris for the south soon, heading for the midi and the sun. As Aznavour sang, La misère est moins pénible au soleil; misery is less painful in the sun.

Greg: They had the right idea. We should have followed their lead.

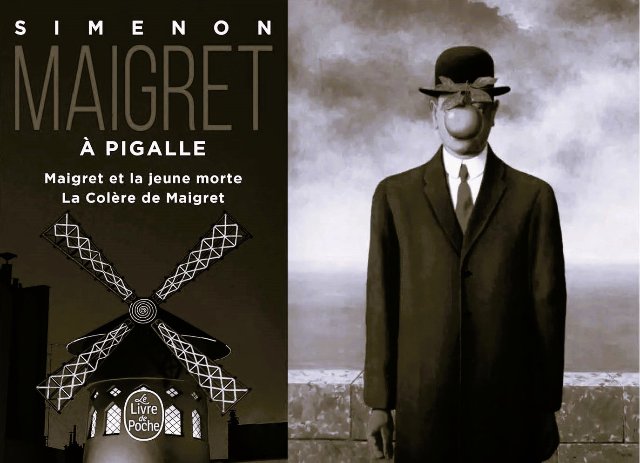

Rafael: And the cops never bothered us about our identity papers there either. They all knew we were from Chez Haynes. The cops chatted with everybody pretty much, and the prostitutes were usually in a good mood. I asked the prostitutes about the maquereaux, the pimps, and the women said they were independent, they weren’t making that much money anyway. The atmosphere in the bar was out of a Jules Maigret scene. I’ve always liked Simenon. He writes simple prose, deceptively easy to read and the stories are intriguing and psychologically tense. I think he’s a great writer.

Greg: Time for a confession. I am ashamed to say that when you first mentioned Maigret to me back then, I thought you were talking about Magritte, the surrealist painter—whom you had probably schooled me about a few days earlier. He (the artist) might have appreciated the juxtaposition. Master of the unconventionally odd and, I later learned, alleged forger of bank notes and paintings when times were tough, or projects needed to be funded. I can fully sympathize, especially, as much of it happened during the Nazi occupation of Belgium when subversion and resistance were all the rage. And one’s physical life depended on it. Getting into trouble then was a lot different than getting into trouble on the fringes of Pigalle in 1976.

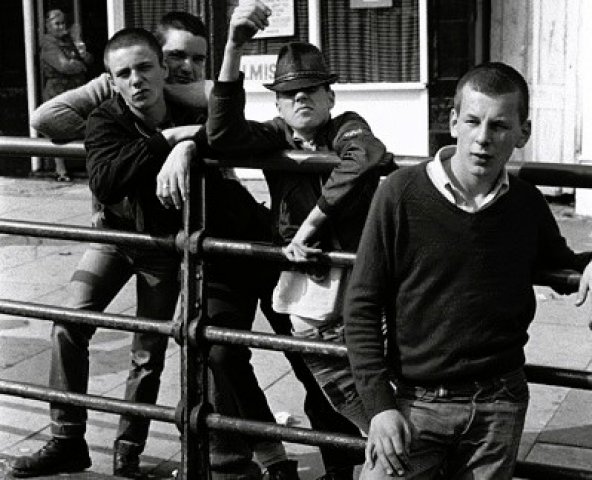

Rafael: We only ran into trouble once, remember? One evening after we left Le Trafalgar. We walked down a small street off Rue des Martyrs. I forget the name of the alley. We saw three young men stumbling toward us. Their voices were loud. I could understand that they were insulting us, calling us sales américains and pauvres cons, on va casser de l’amérloque ce soir, we’re going to give them a lesson, eh, alors les gars? I told you that the guys intended to beat the crap out of us, les amerloques, then and there.

Greg: At least they were not wearing Gestapo uniforms and carrying submachine guns.

Rafael: And then you walked right up to them and started shouting at them. “Who the fuck do you think you are, you cock-suckers? Get the fuck out of here, you wanna fight, you miserable shits?” You put on quite a show there, these kids had seen too many American movies, and they understood the rough talk, especially the word fuck. They stepped back, and you went right on. “You lily-livered freaks, you wanna fight, eh? You wanna rumble? Well, come on, we’re ready, you dumb assholes! Come on motherfucker! Try me! Go on, try me!” By this time, you were screaming at them, right in their faces, and they backed off, then turned and walked away, looking furtively back. That was Pigalle theatre too, eh?

Greg: Sounds more like ‘Pig Alley’ theatre. I don’t remember sounding quite so crazy. But I am not fully denying it. We were into all kinds of theatrical experiments back then. If I recall clearly (and I don’t) I think those guys were pretty young. Even younger than me. But there were quite a few of them. Fortunately, I did not understand much of what they were saying. I do not consider myself stupid, not to the point of physical harm stupid, so maybe I thought we could count on the cops back in the bar if things went askew. I do remember not feeling frightened. But then, I never felt any real street fear in Paris. We could go anywhere any time of day or night.

I may have assumed that the street kids and gangs were not as violent as American, or even British, street kids. I was undoubtably wrong, but not having seen any films with French gangs doing violence on the street (I am sure there were plenty), I foolishly assumed these young men were mostly bark. So, we just needed to bark louder. And that episode was the perfect experiment to test out the theory. That time it worked. I never tried it again. Not even when drunk and arguing with a taxi driver. Which I did a few times.

Rafael: What a performance! I’d never heard the expression ‘lily-livered’ before. Did you make that up on the spot? Great acting there, my friend.

Greg: The expression ‘lily-livered’ or ‘yellow-bellied’ came from a movie I saw. A western. I think it was a line John Wayne said in more than one of his films. But you are right, it was just performance theatre. Which I enjoyed.

We would try things out on street audiences all the time. One of my favourites was up on the Boulevard Strasbourg with Stephen. I think it was during the time we were rehearsing One Day in May. What we were doing there I do not remember. I think the rehearsal space we found was nearby. Anyway, several of us were walking along the street, and Stephen had this white cane and old hat and began miming a blind man. He was tapping the cane in front of him down the sidewalk to the intersection of Strasbourg with another large street. I pretended to be a concerned citizen and went up to him and asked him if I could help him. He said yes, and I took his arm and began walking him across the street. Halfway across, there was a median strip with a large metal lamp post on it. As we approached it, I deliberately walked him into it. Stephen had this great theatrical trick of furtively throwing his hand out at waist height and slapping the lamppost at the same time as his head brushed the lamppost. The loud thump and the sudden snapping back of his head made it look and sound as if he had genuinely smacked his head extremely hard into the lamppost. It worked perfectly. And I laughed. But we had not anticipated the reaction of the Parisians out on the Boulevard that day. Some had been watching the whole sequence and were absolutely horrified that I had deliberately walked a blind man into a lamp post for my own amusement.

Rafael: I can’t help laughing out loud here. It’s just the kind of humor you loved.

Greg: You were particularly vulnerable to slapstick. Anyway, the anger on the street was so palpable and livid and quick that without mentioning it to each other, we instantly both knew that confessing to a theatrical prank would not go over well. I immediately dashed across the rest of the avenue; a cascade of abuse hurled at me as I made off into a side street. Stephen had to play the scene out, explaining he was all right. Unhurt. They walked him the other half of the way across, and he persuaded them he was fine to walk off on his own. We caught up later to debrief. The incident did teach me a lesson about street theatre. You cannot drop your act if you are not letting the audience into the fact that they are an audience. It was not a prank show.

I used that lesson in the theatre course which I taught at the American Center on Boulevard Raspail. In class, I stressed realism in performing. I remember saying something to the effect that acting is not so much the addition of tricks and deceits as it was the shedding of the unnatural behaviors provoked by having an audience in front of you. It was my kind of ‘method’ philosophy at the time. To engage in this authentically (that was a big word at the time), we would often go out into public spaces and perform pre-developed, semi-improvised scenes. I insisted the students had to play it through no matter what happened. They were evoking real responses in the audience which they had to be careful not to mock by letting on it was all pretend. Paradoxically, they needed to shed any desire to ‘perform’ and stay themselves.

The only other time the ‘audience’ reacted as intensely as on that day on the Boulevard Strasbourg was in the metro. On Ligne 4. The metro was a great place to develop a resistance to the inclination to ‘perform’. There was a ready-made relatively fixed audience, used to day-to-day incidents, like Wendy’s uninvited assault. But also, a multitude of musicians and performers walking through the carriages, peddling their artistic wares. So, I figured a little concealed theatre should not be particularly unsettling.

Rafael: Talk about a captive audience. I never knew about these theatrical workshops in the metro.

Greg: I recall you taking part in some of the workshops at the American Center. I don’t think it was your favorite experience. When you were in an intense scene or exercise, you would jump up, saying ‘I’m bored’. Then you would sit down and continue, just to jump up a few minutes later and again say ‘I’m bored’. I never knew dramatic tension could be so deadly tedious. Afterwards, you said you would stick to set design. Which was best as I am not sure shouting ’I’m bored,’ would have worked well in the metro. Although there might have been much agreement.

Rafael: I find all this fascinating. And gee, Greg, I always thought I was a wonderful actor, and here you tell me I was an asshole.

Greg: Not an asshole. Just an honest critic. A typical Paris metro-based scene was usually simple, but the set-up took some preparation. In one instance, at a pre-ordained station two actors, a man, and a woman in their thirties, got on the train and sat down together. They were to behave like new lovers, holding hands, cuddling, saying sweet things to one another, kissing. Not so unusual in Paris. The audience quickly got it. There were some shared looks and smiles, some glanced away but after a short time, they were the center of attention in that section of the train. Even commuters who entered at a later stop got the picture. About five stations later, the woman rose to leave with a final kiss and promises to meet the man later. Just as she left the metro car, waving back at him, another ‘actor’, a similarly aged woman entered the train car. She was the man’s ‘wife’. She saw the first woman leave and wave. Then she saw her ‘husband’. She was not initially upset, just surprised to see him. He was supposed to be at work or with the children—I cannot remember the details. Then it slowly dawned on her, and she asked who the woman was. He lied and told her she was a colleague or some such thing. The ‘wife’ never got very upset or angry but kept probing his answers. Eventually, his lies became so exaggerated and defensive, even nasty, that some of the ‘audience’ members felt they had to intervene. Suffice it to say that he too was forced to exit hastily.

The ‘wife’ traveled on a few more stops with some others in the carriage telling her what had transpired in full detail, one woman even insisting she divorce him. All she could do was nod her head until the next stop where she and I (a very quiet observer) exited. You do not drop out of character in such situations. It was not a gag. Just a class scene. We likely broke all kinds of unwritten ethical protocols. I sometimes wonder how far this work was from Wendy’s unprovoked incident with her mother on the metro. But it was a different time. The time of ‘Pig Alley’. We were always sliding along the edge of ethical protocols of one sort or another.

NEXT WEEK: AWKWARD TANGOS IN PARIS