'Better Late' by Larry Gelbart

Pigs Do Fly Productions in South Florida

By: Aaron Krause - Dec 03, 2025

In Larry Gelbart’s heart-rending and humorous play Better Late, harmony doesn’t always reign in the Baer household. That’s hardly a shocker; what do you expect when a wife and two husbands live under one roof? You might understandably imagine frustration.

But in Pigs Do Fly Productions’ uneven, just-ended professional mounting of Gelbart’s play, irritation also likely spilled over to the audience. Although under Deborah Kondelik’s thoughtful direction the performances were impressively natural and nuanced, drawn-out transitions—some lasting long enough to disrupt the story’s flow—too often interrupted the illusion of real life and the dramatic momentum. In addition, the intermission seemed interminable. Perhaps I wasn’t the only one who felt this way.

Granted, finances may not always allow smaller companies such as Pigs Do Fly Productions to implement state-of-the-art, lightning-quick scene transitions. Still, theater companies should find ways to minimize the time audience members clearly see stagehands rearranging scenery between scenes.

With that out of the way, Better Late illustrates Gelbart’s Neil Simon-like ability to seamlessly merge humor with genuine emotional truth. Both men found the humor in suffering and demonstrated how everyday folks laughed to cope with trying ordeals. You may recognize Gelbart as the man who created the popular TV series MASH*. In addition, he penned the book for the Burt Shevelove and Stephen Sondheim musical comedy A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

Better Late is a romantic comedy/drama centered on a complicated living arrangement involving a love triangle of older adults. Composer Lee Baer and his wife, Nora, take in Nora’s ex-husband, Julian, after his stroke requires rehabilitation and he has trouble selling his condo. Tension builds as the two men reluctantly live together and navigate the history of Nora’s affair with Lee, which ended her 25-year marriage to Julian. Further, Julian’s “temporary” stay with the Baers extends for months due to financial hardship and the need to recuperate.

The situation becomes even more complicated when Julian and Nora’s son, Billy, reveals he is going through a divorce of his own. This adds another layer of family conflict, testing relationship dynamics across generations. Through it all, Lee is trying to concentrate on composing a musical elegy—a piece of music expressing sorrow, lament, or somber reflection.

The tension between the characters and Lee’s struggle to create his musical piece drive much of the play’s comedy and drama. During transitions, we hear parts of the elegy, suggesting a work in progress, and at the end, we hear the final piece.

It’s fitting that Lee is working on an elegy throughout the play. Maybe Julian’s presence prompts Lee and Nora to reflect seriously on the state of their marriage. Additionally, Lee possibly regrets stealing Nora away after meeting her at a party. The elegy might even foreshadow the ending; revealing that the play ultimately confronts mortality doesn’t spoil anything for potential audiences. Gelbart honestly—but not morbidly—touches on death as an inevitability of life.

“It goes by so fast,” Billy says at a cemetery after lingering at his father’s gravesite following burial. He also delivers touching words likely to bring audiences to tears. It’s equally moving that, in place of a spoken eulogy, Lee’s completed elegy plays at Julian’s funeral. The minor chords reinforce the piece’s somberness, underlining the emotional weight of the moment.

Fortunately, Gelbart leavened his serious material with well-placed humor. For instance, while referencing Julian’s stroke, which happened before the play begins, Nora quips that her ex-husband suffered the “Rolls Royce of strokes,” humorously suggesting that Julian suffered a relatively minor stroke.

Another humorous instance occurs when Lee calls Nora on his cell phone while Julian is in the car with him.

“Is that you, sweetheart?” Nora asks.

Both men answer “yes” simultaneously.

While Lee is Nora’s current sweetheart, it’s possible that Julian is still, deep down, also Nora’s sweetheart. Indeed, in Better Late (and in real life), feelings such as love are not always simple. They are often part of complex, layered emotions that may include jealousy, regret, distrust, or even resentment. But the play also reminds us that it’s never too late to forgive others, move on from old wounds, and seek a fresh start.

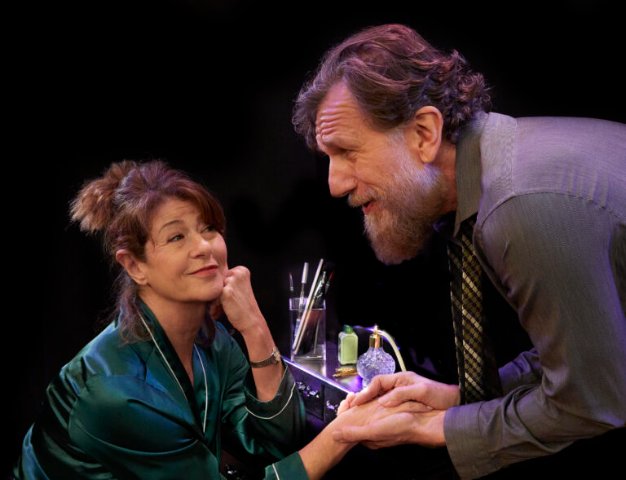

At one point, Julian asks Nora why she left him for Lee. But the smile Galman’s Julian flashes while asking the question suggests that he has forgiven her. Galman, a versatile veteran actor, boasts an expressive face. His smile can instantly light up a room, and his shining eyes enhance this effect. As Julian, Galman sometimes exhibited bright expressions, but his face also twisted into smiles that seemed forced, fitting the character’s awkwardness. Certainly, Julian feels uncomfortable at times in the Baer home and sometimes tries to force charm or humor to break up the tension. With that in mind, Galman’s acting choices often made sense. Once, he placed his hat over his face—was Julian trying to conceal an emotion?

As Lee, Geoff Freitag offered a convincing performance verbally and physically, without forcing anything. His facial expressions often suggested an insecure and emotionally fragile individual with a Charlie Brown-like complex. You sensed that he was down on himself, and such feelings of inadequacy naturally bled into moments of frustration and tension. Undoubtedly, the strain between Lee and both Nora and Julian was palpable. Yet Freitag also conveyed sincere compassion, particularly toward the end of the play.

Patti Gardner, a multi–award-winning, versatile performer, was, as usual, stunningly authentic as Nora. Her unforced voice, natural gestures, unrushed performance style, and expressive face are hallmarks of her fine work. Gardner deftly captured Nora’s strong-willed yet caring personality. You sensed this woman truly loves her family, worries about them, and sweats to do all she can for them. In fact, Gardner also conveyed the weariness of a detail-oriented, meticulous person.

Chad Raven is a young actor with talent and potential, which he flashed as Billy. With his straight face that at times showed strain, Raven convinced us that Billy is young, inexperienced, and conflicted. That’s understandable; Billy just discovered his wife having sex with the couple’s contractor on the Berber carpet that Nora bought during happier days.

The actors performed on Ardean Landhuis’s minimal set. It featured mostly walls and other structures that the stagehands rearranged between scenes to suggest different locales, such as the Baer home and Julian’s house. Oddly, the walls resembled cotton-candy colors (light blue and pink, for instance). The set’s colors seemed a tad too cheery for this play. But if you looked offstage, some of the walls were black. The contrast between light and darkness in the set and costumes neatly suggested life’s contrasting dark and bright moments. (In addition to directing, Kondelik coordinated the costumes.)

David Hart’s sound design was crisp and clear, while Preston Bircher’s realistic lighting design was appropriate for this realistic play. During at least one scene, bright lighting nicely matched Julian’s upbeat mood.

By the end of Better Late, you leave the theater moved and gently reminded of life’s fleeting nature. But you also leave with a sense of resolve and hope. Specifically, the play reinforces a determination to fully embrace life—no matter your age—and to live it “every, every minute,” as Emily so poignantly says at the end of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town.