James Aponovich Part Two

Is Conceptual Realism an Oxymoron

By: James Aponovich and Charles Giuliano - Dec 13, 2011

Beth Johansson and James Aponovich have been posting weekly on their blog. It tracks text and images in a project to complete a painting a week in a year. In June all 52 works, and a few furniture collaborations, will be exhibited at the Clark Gallery in Lincoln, Mass. This is the second and final installment of a dialogue with Aponovich about this demanding project. We have followed and written about the artist and his work since a retrospective at the Currier Gallery in Manchester, New Hampshire in 1985. Tracking the work of a realist painter entails increments of ever more refined technique over an extended span of time. It entails intensive concentration and the work ethic of daily labor in the studio. In that sense James tends to describe himself and discuss the work from the point of view of a proletariat. That does not include hanging out with the movers and shakers of the art world. And for ambitious critics it is not a smart career move to write about the work. Not that we particularly give a fig. The paintings, by the way, are absolutely fabulous.

Having been out of the New York art world for several years he recently joined the distinguished Hirschl & Adler Gallery. He is scheduled for a one man show in 2014. He will continue to be represented by the Clark Gallery.

Charles Giuliano What keeps you from becoming bored with the project to complete a painting a week for a year?

James Aponovich Oh, come on Charles. If I had a commission to paint portraits of Madame X and Mister Y then that’s what it’s like. You go to work each day to execute your craft. At the end of the day you come back with little or no exploration. You haven’t added a brick to the edifice you are trying to build. Or taken a brick off the load you have on your back. But when you are unfettered from that. Taking the blank canvas and seeing what comes out of that. It may be delusional. Which is possible particularly at our age but these works have an explorative nature for me. I find that very rewarding. I’m not bored by them at all.

CG Do you feel excited and motivated about going into the studio each day?

JA I’m 62 now and have been doing this all of my professional life. If we make enough money that on any given day we can wake up, have a cup of coffee, go into the studio and work all day. To me. That means that we are blessed. That’s what the whole thing is about. Of course, as you get older you have to think ahead to potential health issues. What if we can’t continue to paint? For the time being nothing has changed at all in terms of how I go into the studio every day.

CG So a year from now there will be 52 paintings and Dana (Salvo of Clark Gallery) will show them.

JA Right. There will probably be more. This morning I got a call from a furniture maker. New Hampshire has some of the leading studio furniture makers. I have had three collaborations with David Lamb who is one of the best. I’m James Aponovich so together we’re the Lambovitch Brothers. I collaborate with him to place panels within pieces of furniture. There’s a tradition for that particularly within Italian and German work. We are working on one now that will take a year to do. That will be a part of the Clark show as well so it will be quite a show.

CG Do you have a base of collectors?

JA Ones we started off with like the Stones, they both died. Stephen died about fifteen years ago and Sybil died five or six years ago. A lot of those older collectors are deaccessioning their collections so in a sense it’s hard to find new ones. A lot of those collectors were committed to the art of their own eras the ‘50s or ‘60s. They collected for thirty, forty, or fifty years. It’s harder now to find the younger collectors. Which is why someone like Dana is so invaluable. He goes out and inculcates that. Younger now means anybody from thirty to fifty.

CG You’ve never been a part of the mainstream art world. Never having been in fashion it would seem that you are not out of fashion.

JA I totally agree with that. If people ignore you that also creates the greatest freedom. There is the British actor William Hurt. He has said that the worst thing that an actor might hear is how good their voice sounds. If he encounters a young up and coming actor, whom he feels intimidated by, he compliments them on their voice. In other words he makes the younger actor self conscious and invariably that will destroy them. Anonymity is ok. As long as you sell the paintings does it really matter? If I’m not in the Globe or Sunday Times. It’s great to be that but on the other hand what is it?

CG A few years ago when we were sitting in your living room there was only one small painting by you, of Strawberries, on the walls. You said that you gave it to Beth. There was also very little in the studio. With so little inventory is if fair to say that you sell everything that you paint?

JA That’s true. If I give Beth a painting for her birthday, as I did this last February, she will not sell it no matter what. So that saves a painting.

CG How about Ana (Aponovich) do you give paintings to her?

JA Yes. Same thing. I gave her a Strawberry painting which I still have here. I asked her if someone wants to buy it can I sell it and give her the money? She’s young and could use the money. She said “No. I don’t want you to sell it.” I was amazed by that and very impressed.

CG At our age we have to start thinking about legacy. Artists do not give enough thought to their estates. The heirs generally want to convert the inventory to cash. I recently spoke with the family of a prominent artist. I asked how much work they had. It was about 100 paintings. I suggested that they put an increment of sales into a fund. This would be used to support exhibitions, research, cataloguing and publications. Some years ago I was researching an artist. When he died it all went to his wife, they had no children. Her bank advisor got the work back from a major gallery and sold it from out of the vault. It was basically a fire sale which devalued the work overall. It ruined the market for a number of years. Even notebooks were pulled apart and pages sold separately. Unsigned sheets were given an ugly estate stamp. When she died the financial assets were divided through her relatives, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Phillips Collection. There was not a dime to support research on the artist or to create an archive. The legacy of the artist went into freefall and it has taken decades to recover. But it is not where it should be because there are no advocates.

JA I agree with you. It’s like life insurance. You’ve got to do it.

CG Some years ago you were in financial jeopardy when you took a commercial loan to finance a series of color lithographs. The bank called in the loan and you were strapped to pay back the money.

JA Every year we get requests for those old prints. When we sell them its like Mana from Heaven. We went out on a limb back in the ‘80s to get them done. But if you do the math they have paid for themselves over and over and over again. To do them was very intense working with Herb Fox.

CG Have you done Giclee editions?

JA That’s something that I can’t get my head around. It’s a reproduction of a painting that you sign but has nothing to do with the artist’s intervention. A lot of people don’t care. They want something to cover the walls. All they care about is the color, signature, and number on the print. That’s it. Plus it’s under a thousand bucks. That’s a whole market and I haven’t gotten to where I am going out and seeking it. I’ve done some Giclees. In fact every important commission I do I bring to Hunter editions and have it digitally scanned and make a Giclee which I give to the collector as a part of the commission. And I keep one. But I have yet to edition one. If it’s a benefit for an art museum I’ve done that twice. I make a painting and a Giclee. The museum gets the money and everyone is happy. That’s a part of what I do but that’s all.

CG If you had an exhibition and did an edition, say a hundred, of an image from that show wouldn’t it be an additional revenue source?

JA Of course. But I’m not sure it wouldn’t cheapen the entire show. It might add a few hundred dollars but not several thousand. Would it inhibit the sale of a painting for $60,000? Would it be worth it? I would rather that a collector bought a small painting for three thousand dollars than a cheap Giclee print for say $800.

CG Have the prices changed over the years.

JA In California (Hackett Freeman Gallery) they were quite pricey. I couldn’t afford one. What Dana sells, a small one around 8 x 10,” they are usually around $10,000. They go up to between $75,000 to $90,000. Those are the really big ones which I don’t do anymore because they are such a pain in the ass to get around. To transport. It sounds very pedestrian but that’s the case. The biggest one you’re going to see is five feet by four feet. That’s as big as I’ve every painted. Right now my biggest paintings are about 30 x 40” That’s fine. It’s big enough. I can set them up in the studio. Artists paint bigger because they think it’s more impressive. In some cases it is. When we went to MoMA to see the Abstract Expressionist show those paintings were knock outs. At 8x9’ they were more impressive than they would have been at 30x40”.

CG Why would you be interested in abstract expressionism? That doesn’t sound like you?

JA I love that stuff.

CG We found a chink in the armor.

JA Hey Charles. I’m a well rounded guy.

CG I thought you were a Pre Raphaelite.

JA Beth has been reading biographies of these guys so we got to know them intimately through her reading. Rothko to me is a God. Oh yeah. I’m not telling you anything. But if you look at his pictures that’s pure power. I’ve always been a big fan of Franz Kline since my Alan Stone (Gallery) days. De Kooning. The Abstract Expressionists was a very interesting show to see. The first part was what they called The Explorers. The Gorkys, Pollocks and de Koonings. Then they got into, what was the word? The Colonizers. The Second Wave. Motherwell came in. Then you got in to the Third Wave, which became almost trite. The last rooms.

CG So what made you go in the other direction? (Realism)

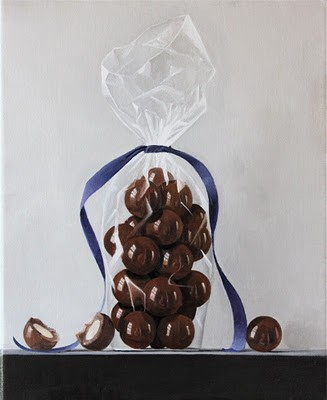

JA Art is not conceptual for me. It’s perceptual. I really enjoy looking at the absorption in surface. It makes me a naturalistic painter. It makes me what they call a realist. But to be just that, and there are a ton of realist painters who are just that, is not really sufficient. There’s something more to painting and that something more, that something else, that interactive thing is worth exploring. It transforms the perceptual into something that becomes more conceptual.

CG In the mainstream art world today you would be regarded as a paleontologist.

JA In other words a dinosaur. You have to follow that because of your work as a critic and historian. You follow that sequence. I ignore it. If someone gave me a quiz about what’s happened over the past ten years in the art world, no question, I would flunk. Who is to say that I’m wrong? Those who are scurrying after what’s happening now? Those who follow fashion, if they wear the same clothes for too long, they look silly.

CG The premise of modernism and an avant-garde is that each generation builds and expands on the work of prior and past generations. If an artist such as yourself opts out of the modernist paradigm it disrupts the notion of experimentation and progress. Then what?

JA Then I become the ascetic the contemplative. Who sits and endures the world.

CG The irony is that if your painting is in a museum collection a hundred years from now the curator won’t particularly care about the issues of the era in which it was created. The work will have a more enduring quality that supersedes the aesthetic imperatives of the moment.

JA Yes. They are just going to look at the God damned picture.

CG Throughout art history there are always niche artists who fall out of the mainstream trends. When El Greco settled in Toledo he continued with mannerism long after it had fallen out of style. In that sense he was a provincial artist. The American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder fits no convenient movement which might also be said of the visual work of the poet William Blake. There was the British eccentric who did small paintings with tiny fairies.

JA Richard Dadd.

CG He was on the periphery. An eccentric. But you look at the work today and it is astonishing. The art world likes to create movements and categories then herd artists into them. To bundle them for the convenience of theoretical and historical discussion. We talked about Abstract Expressionism. It is such a broad term that includes everyone from Pollock, Gorky and de Kooning, to Rothko, Ad Reinhardt and Barnett Newman. Clearly there are significant differences in their work. You can’t define them all with broad strokes of the same critical brush. In that sense as we are discussing you do and do not remain confined within standard definitions of realism. It is merely the shorthand and most readily available term.

JA Back in the 1950s when I was a kid there were these little license plates you could hang in your car which showed which club you belonged to. Which hot rod club. There was one that said Lone Wolf. No Club Lone Wolf. I said ‘That’s the one for me.’ That was before I started painting. But that made sense to me. The Lone Wolf. No Club. That’s been my bumper sticker for the art world.