Hans Henze's Sailor Betrayed

Simone Young Conducts a Masterpiece at Vienna State Opera

By: Susan Hall - Dec 23, 2020

Vienna State Opera

The Sea Betrayed.

by Hans Henze

based on Yukio Mishima's

The Sailor who fell with Grace from the Sea

December 2020

Vienna, Austria

The Vienna State Opera has recently streamed their live production of Hans Henze’s The Sea Betrayed, a title translated with the approval of Yukio Mishima, the famed author of the novel on which the opera is based. The opera premiered in Berlin in May of 1990. Audiences in this country were not initially attracted when it was produced the following year by the San Francisco opera. The War Memorial Opera House was half empty.

No one is better able to understand Mishima’s work better than Henze. Mishima struggled to deal with the loss of traditional Japanese culture as his country was besieged by Western powers and then seduced by them. From Mishima’s point of view, all of Admiral Perry’s boats in Tokyo Bay should have been blown up. Instead Mishima was left to write about culture lost and what it meant to an individual.

In The Sea Betrayed, a sailor is curiously reminiscent of Pinkerton, who seduced and betrayed a Japanese maiden, and then took their half-Japanese son back to the United States. Here the sailor Ryugi, poignantly sung by Bo Skovhus, is drawn to leave the sea on whose ‘culture’ he depends, to live on land with Fusaka, a beautiful Japanese woman. She sells bespoke Western clothing in her shop.

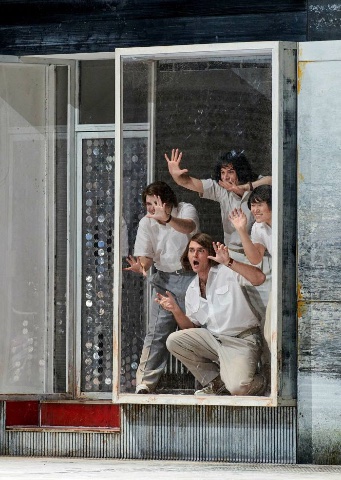

Her thirteen year old son, Noboru, is the center of the piece. Josh Lovell, a tenor from the Ryan Center at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, captures the pubescent boy’s mixture of Clockwork Orange and Lord of the Flies. Driven by the emotions of Greek myth, he is left to articulate the Mishima message. The soul of the sailor is at sea.To leave the sea is to empty himself of being. His only salvation is return, dead or alive.

This is a story about our souls. It has been noted that humans did not discover that they had souls until they heard musical notes. Discover them they did. Many of us remember as the seminal moments of our lives a Wagner chord, a Mozart melody, or the crashing intertwined chords and musical escalations of a composer like Henze.

This is an emotionally wrought work. Its intellectual base need only be clarified because Mishima is often misunderstood. He becomes a clown if we do not grasp his attempt to restore Japanese culture to Japan, and to die because he fails. This opera is another version of that betrayal.

The story or theme of an operatic work is joined with its music. Yet, because a melodic line often sits on top of orchestration, the story and the music remain separate. Wagner addressed the split by creating chromatic harmonies of ineffable beauty. Liebstod from Tristan sounds like eternal love, always to be striven for and never achieved. It is the yearning in the music which draws us back again and again to Wagner, a desire which is tantalizingly unreachable.

Unease is another central feeling of operatic composition. In the 20th century, Benjamin Britten creates unease notably in Peter Grimes. Henze despised his birth culture-turned-Nazi but loved the long history that preceded Hitler. He did not abandon German music, despite his revulsion. His work is filled with unease created by this decision. Unease can be as tantalizing as yearning. For as we discover Henze's disturbed notes, we cannot leave unresolved. Yet they cannot be resolved.

Light and darkness splash out of the chords and rhythmic progressions as conducted by the superb Simone Young, The maestro was due back at the Metropolitan Opera this spring after an inexplicable twenty-five year absence. She masters this opera, making sure that all the elements are embedded in the big picture. The composer’s palette, with lines intertwined with stray variants, powerful rests and wrenching desire and fury, is brought forth.

How can we listen to the lovely Vera-Lotte Boecher singing Fusako and not feel her joy at sexual re-awakening? Ryuji’s’s relation to the sea, noted as buoys clanging and water rising and falling, lets us hear his soul's desire. And Noboro, the son, in the fashion of Greek myth, can not bear his mother choosing another man. A member of a gang, his fury becomes a murderous weapon in music and sprechstimme.

The work does not end in otherworldy consolation, although the sailor’s return to the sea suggests one. Death drives opera, which struggles to give it meaning. It is a grand struggle. The music has an eviscerating lilt. Music says only what an ear can bear to hear, and this is perhaps why the harshness of Mishima’s vision repulses, even as this work engages us.

In the hands of the directing team of Jossi Wekber and Sergio Morabito, the Vienna State Opera has done justice to this magnificent work of art.