CAVS Fellows Gather to Celebrate

50 Years of Art Science and Technology at MIT

By: Charles Giuliano - May 18, 2018

Recently, former fellows of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies assembled to celebrate during a reception for a special exhibition in the Mass Ave storefront gallery of the MIT Museum.

Fifty years ago the Hungarian born painter and experimental photographer, György Kepes (1906-2001), founded a program to support artists as fellows and educators conflating a heady mix of art, science and technology. Its students earned Master of Science in Visual Studies (MSVisS) degrees.

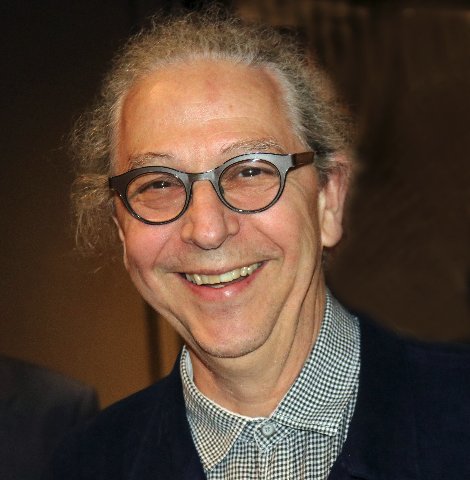

In every sense, as was evident during the evocative gathering, they went forth and multiplied. It was truly a global event. Today many alumni are successful artists as well as academics. When founded CAVS was unique, but through its core participants, there are many universities with similar programs. We spoke with deans and professors including Lowry Burgess of Carnegie Mellon, and Bill Seaman professor of art, art history and visual studies for Duke University. It was fun to interact with a former colleague, Greg Garvey a Canadian professor of game design and development.

When Kepes founded CAVS he brought to America concepts rooted in the Bauhaus, an arts academy with a remarkable faculty of artists, architects, and designers. It flourished but ended when the Nazis came to power. Kepes was one of many ancillary artists who came to America. Initially, he was part of the effort by the Hungarian artist, Lazlo Moholy Nagy, to establish a new Bauhaus in Chicago. That ended with his death in 1946.

Kepes was replaced as director by the German artist, Otto Piene (1928-2014), one of the founders, in 1957 with Heinz Mack, of Group Zero. In 1961, Günther Uecker joined them. Many technology-based, experimental artists worked with them in the ensuing years. Emerging after the war, in which Piene fought as a teenager, there was a mandate to explore art not rooted in the Germanic traditions of romanticism and expressionism. The new work employed aspects of science/ technology creating non objective abstraction.

In every sense their work, as well as that of CAVS fellows, explored the elements of earth, air, fire and water. With helium filled, inflatable sculptures Piene became a pioneer of Sky Art. One of these works is compressed into the museum's lobby. He also created fire paintings, as did Yves Klein, who showed with Group Zero.

Under Piene, the MIT program pursued a new direction. It was difficult for Kepes fully to let go and there were clashes.

From 1968 to 1971, Piene was the first Fellow of CAVS. In 1972, he became a Professor of Environmental Art at MIT. In 1974 he succeeded Kepes as director of CAVS, in which position he served until September 1, 1993. Until his death in 2014, he commuted to a studio in Dusseldorf where he remained active in European projects. Arguably, based on numerous museum retrospectives, he is better known there.

Despite the astonishing reputation of CAVS the Boston art world and its critics paid little attention to groundbreaking accomplishments. Its focus is rooted in the expressionist figuration that Piene rejected. In Boston's conservative and dominantly academic cultural community there has never been a comfortable fit for the avant-garde. Piene’s CAVS was uniquely a Cambridge thing.

A highlight of CAVS was its collaborative work Centerbeam for the 1977 documenta 6 in Kassel, Germany. The 144’ performative sculpture combining lasers, holograms, steam and other aspects was also installed on the Mall of Washington, DC, in 1978.

My wife, Astrid Hiemer, was administrative officer under Piene. She has written vividly of participating in Centerbeam. During the recent celebration there were many interactions with former fellows including those who participated in the iconic documenta project. This is a link to her review of the current MIT Museum exhibition which will be on view through January. She was a translator / editor of Piene's massive book and has written extensively on his work and Group Zero.

In typical MIT fashion the anniversary was less about the past than a bold step into the future. While the exhibition offered aspects of accomplishments it fell short of sketching its unique and complex history. In addition to an eclectic and confusing installation of a few works in the main gallery there were a few more glimpses in the upper spaces.

Most satisfying was a gallery György Kepes Photographs: The MIT Years, 1946-1985 which is on view through July 15. Because of the scale of the images there was a critical mass that allowed for enjoying the experimental work in depth. Many pieces, photograms, were created without the use of negatives. Various objects were placed on light sensitive paper and then developed. The artist is also know for sensual paintings with rich colors and surface textures enhanced with sand.

There were two other galleries. One was devoted to holography by Harriet Casdin-Silver, Dieter Jung, and Lowry Burgess. Casdin-Silver, who died at 83 in 1983, was represented by Boston’s Gallery Naga and had a retrospective at the DeCordova Museum. In general, the lighting of holograms was disappointing. It must be precise for the full impact of 3-D illusions.

There was a gallery devoted to the light sculpture of Piene. By current technical standards the play of light and shadow in a dark space is compelling but uncomplicated. What was remarkably bold and experimental for its time seems less so today. This is an inherent challenge for artists using technology which morphs and develops at warp speed.

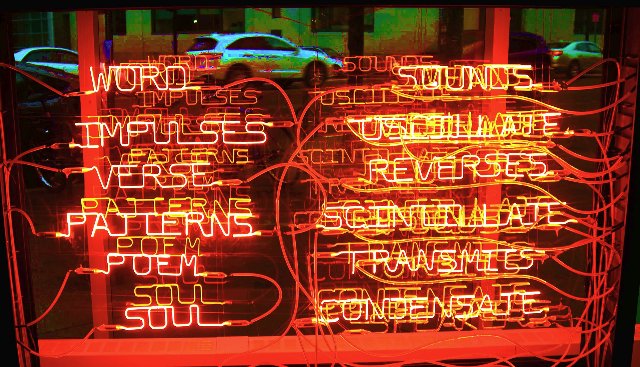

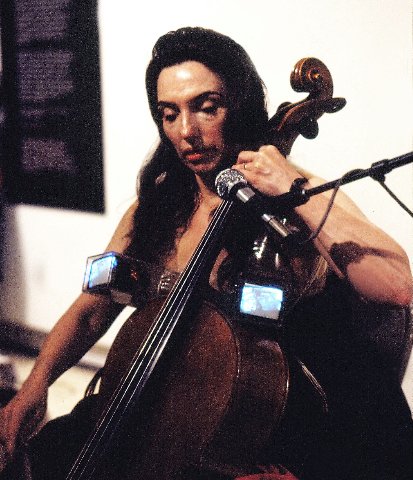

As works age there are issues for curators and conservators to maintain and restore them. Nam June Paik, for example, is represented in this exhibition by a TV cello (owned by Piene and loaned by Elizabeth Goldring Piene). It is composed of lucite boxes and now antique analog televisions. It is difficult to find the parts to keep them running. There are similar challenges to find the now obsolete fluorescent tubes for light sculptures by Dan Flavin.

Artists using off-the-shelf, industrial materials are well advised to stockpile them. Arguably, this is nothing new. Leonardo da Vinci used oil paint for his ersatz fresco “The Last Supper.” His use of new medium, oil paint, and old, fresco, technologies did not work. Oil and water (fresh plaster) do not mix and the iconic painting has been an enigmatic ruin ever since.

Related to the CAVS anniversary was a two day symposium. It represented the latest interdisciplinary advances. We attended the Friday panels and papers. I comprehended only an increment of the presentations. Astrid commented that it was much in the spirit of MIT and numerous such events that she helped to organize. It was presented by the department of Art Culture and Technology (ACT) which CAVS merged into several years ago. It maintains and provides scholarly access to the extensive CAVS archive.

The Zooetics+ Symposium began with sessions “What Does Ecosystemic Thinking Mean Today” and “Knowledge Production Through Making and Living with Other Species,” discussing the habits of thought associated with cybernetics and the transition towards new thinking, inspired by sympoietics. The day ended with a session speculating on what non-human imagination could look like “The Radical Imagination: Toward Overcoming the Human.”

The next day’s program explored devices for ecosystemic thinking, discussing relevant artistic methods and practices in the panel “Artistic Intelligence, Speculation, Prototypes, Fiction.” “Creating Indigenous Futures” explored bringing Indigenous values together with science and technology. The need for other, alternative vantage points—of species, of time, of traditions, of beings were addressed by “Futures of Symbiotic Assemblages: Multi-naturalism, Monoculture Resistance and “The Permanent Decolonization of Thought.”

The symposium concluded with a roundtable and launch of a new artistic research program “Sympoiesis: New Research, New Pedagogy, and New Publishing in Radical Inter-disciplinarity.”

Zooetics+ was accompanied by performances and installations by Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa, Allora and Calzadilla, Rasa Smite and Raitis Smits, Rikke Luther and NODE Berlin/Oslo.

Emerging from those sessions we were up to speed with the latest developments. But there was a unrequited urge to know more of the history and accomplishments of CAVS. In the ground floor gallery there was a tantalizing, grainy but evocative video projection. The redoubtable avant-garde cellist, Charlotte Moorman, was lofted by a Piene inflatable sculpture.

She was notorious for performing nude often in comical collaborations with Paik. He created for her a TV Bra which she wore for a performance during a Paik opening at the Rose Art Museum. An early curator for the museum, Russell Conner, was a pioneer in presenting experimental television which later evolved as video art. Piene and Aldo Tambellini collaborated in works that were broadcasted by WGBH in Boston.

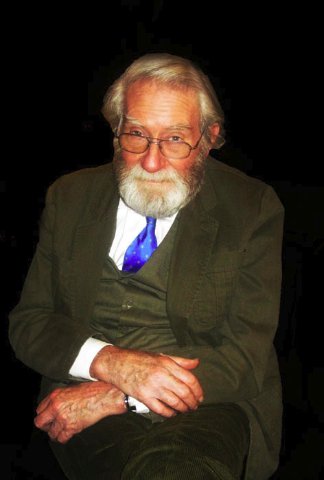

Greeting the former fellows there were remarks from MIT Museum director, John Durant. The until recently, acting director of ACT, Gediminas Urbonas, also addressed the fellows. They could have been more anecdotal and informative but for those congregating to celebrate there was no such compelling need. They had lived CAVS and gathered as a clan, family of remarkable artists, and progressive experimenters.